The Modern Couples show currently at the Barbican has eyes slightly too big for its own – or at any rate for my stomach. Nevertheless, it is, in the present climate for the visual arts, an event that is both timely and important. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that it’s very much the kind of exhibition that Tate Modern, with it’s increasing obsession with gender, should have offered us and hasn’t. It’s good that the Barbican Art Gallery has stepped in to fill the gap, and better still that there’s a stonking excellent hardcover catalogue to memorialise their effort. Not cheap, at £40, but packed with information. Maybe too much information, if there can be such a thing. Fewer artists featured and more in-depth coverage might have been a good thing. Boggles the mind. The Modern Movement in art and design of the first two-thirds of the 20th century, which is what the exhibition strains to cover, is a huge chunk of territory.

Some of the partnerships it features were obviously unequal. – ELS

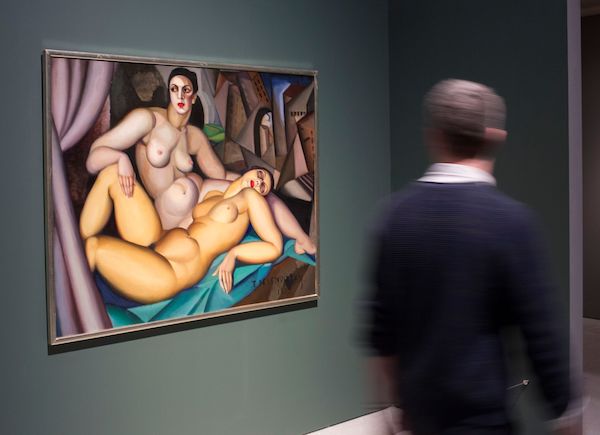

To be a tad unkind, the effort works better as a catalogue, print married to images, pages one can turn back and forth than it actually does as an exhibition. There is a problem with scale. Not many big pictures (or for that matter large sculptures) to focus your attention. Les Deux Soeurs (1922), a significant canvas by Tamara de Lempicka, is one of the few exceptions. It shows an apparently lesbian couple: one nude reclining, swooning even, in the other’s lap.

Though the theme of the show is the theme of sexual relationships, citing this painting may give the wrong impression. The exhibition is about sexual relationships of every variety, as these affected art as its emerged into Modernity. It features more heterosexual pairings than it does homosexual ones, and quite often the artists it features seem to have been pan-sexual, ready to transfer allegiance from a partner of the opposite sex to one of their own gender, or – on occasion – vice-versa. Its central theme, however, is the need to give much more credit to female participation in the evolution of the Modern Movement

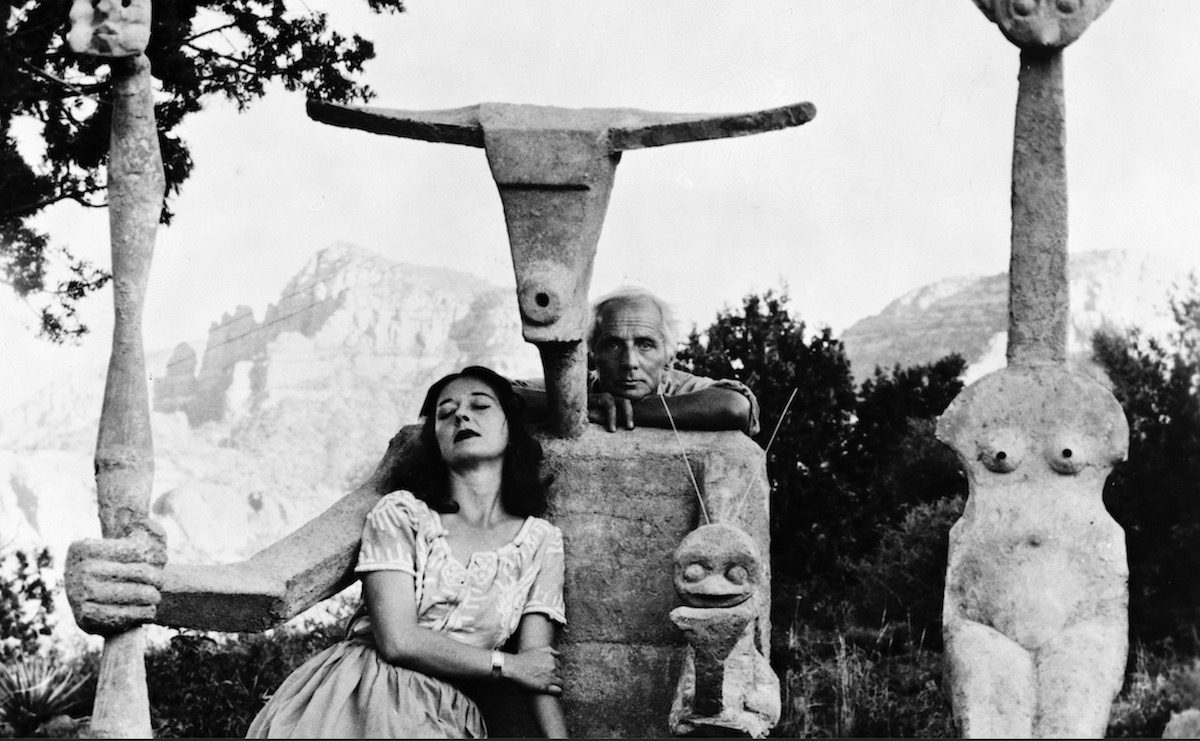

Some of the partnerships it features were obviously unequal. Dora Maar, a mildly exciting maker of photographs, was never the creative equal of Picasso, whose lover she was for some years. But the women in these innovative partnerships, those with men, not creative women in lesbian relationships, were often the prisoners of their own assumptions, as these, in turn, were shaped by the society of their time. They were instinctively backwards in coming forward. Or unwilling to claim full credit because of the problems this might cause with the male ego they were paired with, and to which they were emotionally attached.

One striking feature of the show is the stress in places on the International Surrealist Movement. The core of Surrealist creativity was a belief in the need to listen to and respond to the promptings of the inner self. In this, it owed much to the discoveries and teachings of Freud. But Freud was no friend to the idea of women’s independent creativity.

“Women oppose change, receive passively, and add nothing of their own,” he wrote in a 1925 paper entitled The Psychical Consequences of the Anatomic Distinction Between the Sexes. Later, speaking to his biographer Ernest Jones, he said: “The great question that has never been answered, and which I have not yet been able to answer, despite my thirty years of research into the feminine soul, is ‘What does a woman want?'”

Maybe some of the images included in the Modern Couples’ show might have enlightened him.

Yet, even here, the message is a little scrambled. It’s a telling feature of the show, and one of its major weaknesses, that it relies so much on photography for its narrative. What do we know about the position of photography during the period it covers? First, that it was still a demotic art – respected, but a tier down from the supposedly ‘big’ stuff. And secondly, that it was the art form in which the idea of the amateur and the professional most wholly overlapped. The age of the Great Big Photograph was still to arrive. And even now it is more often made by men than it is by women

Modern Couples Art, Intimacy and the Avant-garde The Barbican 10 Oct 2018—27 Jan 2019