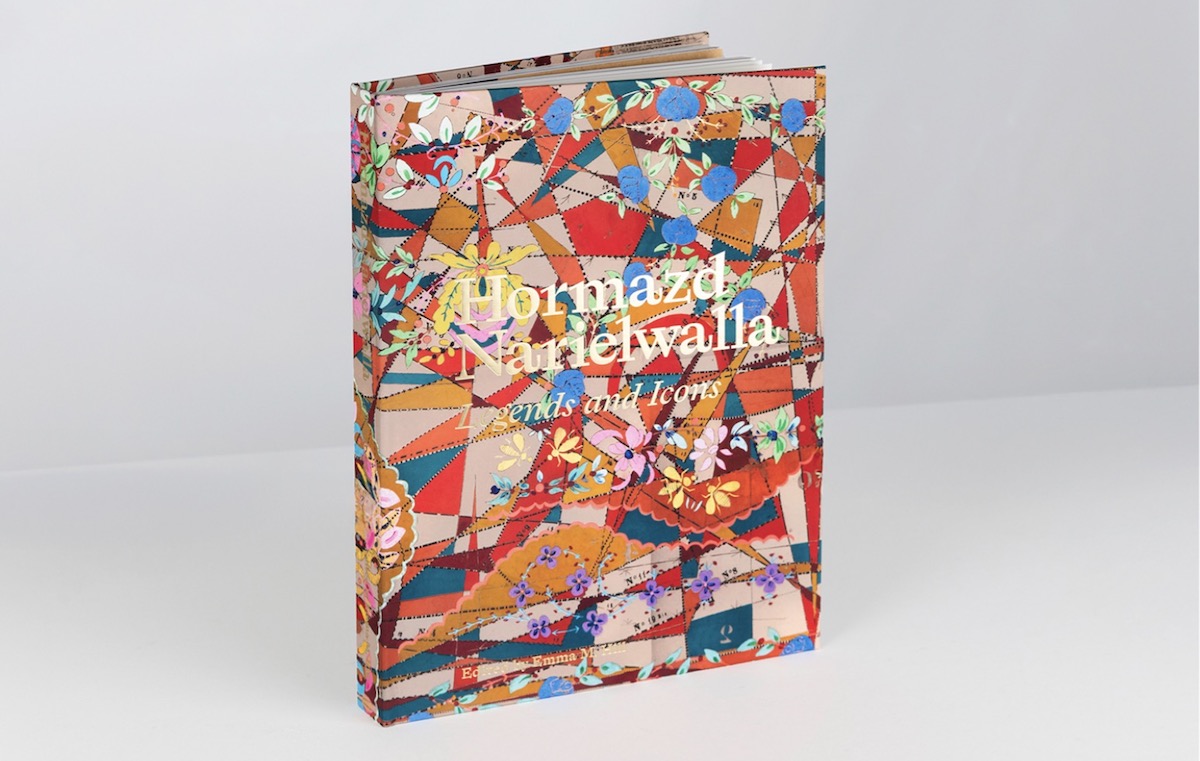

Legends & Icons, edited by Emma M. Hill, feels like you’re walking into an artist’s studio after hours — scraps still on the floor, tools abandoned mid-thought, ideas vibrating in the air. This is Hormazd Narielwalla’s first major survey, and it arrives with the weight of a tombstone and the spark of a practice still stretching its limbs. At 260 pages, foil-blocked and lushly produced, the volume is less a retrospective than a long, complicated inhale.

Narielwalla has never been an artist you can neatly pin to a single discipline. Printmaking, sculpture, artist’s books — sure, all of that is in the mix. But his actual signature sits somewhere stranger, somewhere more fragile: the antique, abandoned tailoring patterns he resurrects and reorganises into abstract compositions. Patterns once meant to shape a garment become, in his hands, metaphors for bodies, memories, and entire, shifting identities. These salvaged templates — utilitarian things, really — become ghostly stand-ins for people who may never have known their shapes were destined for an afterlife in contemporary art.

The book walks us back to the very beginning: A Study on Anansi, his 2009 collaboration with Sir Paul Smith, which already hinted at his instinct for mixing cultures, layering narratives, and imagining the human form as something not fixed but continually under construction.

From there, the trajectory is brisk, sometimes dizzying: commissions for 45 Park Lane and Hackett, a residency at the V&A, a sculptural installation for the Crafts Council, a monumental cosmic sprawl titled Expanding Universe at the Royal Geographical Society last year. If the career arc looks neat on paper, the work itself feels anything but. Narielwalla is an artist who follows tangents, trusts instinct, and understands that the most interesting stories often come from material that’s already lived a life.

Several essays deepen the context — contributions from Nancy Campbell, Isabela Galvao, Melanie Vandenbrouk, Piero Tomassoni and Dr Michael Petry each refracting the work from a slightly different angle. Campbell, in particular, draws out the cultural hybridity at the centre of his practice. Born in India, Narielwalla arrived in the UK in 2003 to study fashion and carries that lifelong negotiation between places, identities, and expectations. His collages often feel like maps of somebody mid-transformation. They pose simple, unsettled questions: Who are we? Who were we taught to be? Who might we permit ourselves to become?

The tailoring patterns — delicate, faded, occasionally torn — set the tone for everything. Narielwalla reads them as “beautiful abstractions of the human body,” little diagrams of lives once tucked into bespoke jackets or military uniforms. Working over these fragile grids, he inserts his own visual language: arcs, blocks of colour, geometric flourishes, fragments arranged with a Cubist’s fondness for compression and a storyteller’s appetite for reinvention. The results can be quietly lyrical or theatrically bold, sometimes within the same series.

Take Dead Man’s Patterns (2008), his elegy constructed from the bespoke suit templates of a deceased Savile Row client. It’s morbid on paper but surprisingly luminous in execution, a meditation on mortality that feels more like a whisper than a dirge. Or his 2013 Crafts Council commission, which mined military uniform patterns dating from 1850 to 1947 to confront the legacies — and wounds — of the British Raj. Even Lost Gardens, his ongoing series inspired by a vanished rose garden from his childhood, slips between memory and cartography, nostalgia and construction.

The book doesn’t shy away from the artist’s ongoing fascination with cultural icons either. The V&A’s 2018 Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up sparked a set of collages celebrating Kahlo’s use of clothing as armour and autobiography. Chanel appears as a sculptural abstraction of couture discipline. And then there’s Diamond Dolls (2020), a shimmering parade of Ziggy Stardust figures. These aren’t Bowie portraits so much as reincarnations — forms caught mid-shift, half-mythic, joyfully unpinned from conventional gender. It’s telling that Bowie was an awakening for Narielwalla, an early revelation in the power of self-invention.

If the book has a thesis — not stated outright, but beating beneath the pages — it’s that identities aren’t fixed; they’re patterned, cut, adjusted, reassembled. We inherit shapes from culture, family, clothing, and history. And then, if we’re lucky, we find ways to redraw them.

Legends & Icons documents seventeen years of work. It offers a blueprint for how an artist can build a life from remnants, fragments, cast-offs — and in doing so, create something startlingly whole. It’s an invitation, really: to look again at the patterns we’ve been handed, and imagine what else they might become. – PCR 2025