We face the world in which it appears ever more likely that a Clash of Civilisations will be played out on the world stage, potentially with weapons of mass destruction, as the axis of the world appears to have shifted significantly in this year of political shocks.

The prevailing political narrative seems to suggest that the response to an increase in the frequency and savagery of terrorism, with its resultant impact on the refugee crisis, is to build walls and ban particular religious groups in order to protect national boundaries. The potential of this narrative for the further escalation of conflicts is huge. Nationalism and religion both have shadow sides which set one group against another and encourage their followers to sacrifice their lives for a greater cause in the ensuing conflicts.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks talks about this as a pathologising dualism: ‘dualism happens when a people feel humiliated beyond any kind of comprehension … dualism always asks the question who did this to us? … we’ve been following God, so therefore somebody who did this to us is the enemy of God, the greater or lesser Satan … once you get into a dualistic situation … civilization is on the road to self-destruction, there’s no sane way out of this … it’s a scenario that has no happy ending unless somebody pulls out of it because dualism is one of those totalizing belief systems that you can never actually break free of once it’s got hold of you.’[i]

The Arts are inevitably caught up and impacted by these narratives and conflicts. ISIS destroys the art of civilisations wherever its reach extends, most notably at Palmyra. Brexit threatens to cut off EU arts funding without alternative national sources existing, as demonstrated by the threat from austerity cuts to the wonderful New Art Gallery Walsall. This may leave the Art world, despite its avant-garde image, ever more reliant on the largesse of capitalism and consumerism. Then, in the US those who will come to power in 2017, are those who have consistently sought to censor and neuter the liberal Arts.

The obvious answer, where this state of affairs relates to religion, might seem to be a secular rejection of the messages and practices of religion; essentially the approach of the New Atheists which is, through rational argument, to seek to undermine religious thought and practice. However, while in secular environments this approach bolsters secularism, in religious environments it has the opposite effect producing a sense of being under attack from secularism which makes violent responses more likely, rather than less.

The answer to religious violence, Jonathan Sacks has argued, can only be found in religions themselves.[ii] The political narrative of the Clash of Civilisations and the aggressive secularism of the New Atheists will only exacerbate the situation. Sacks’ great contribution to these debates is to explain why the answer to religious violence can only be found within religion itself and among those who understand that religion only gains influence when it renounces power.

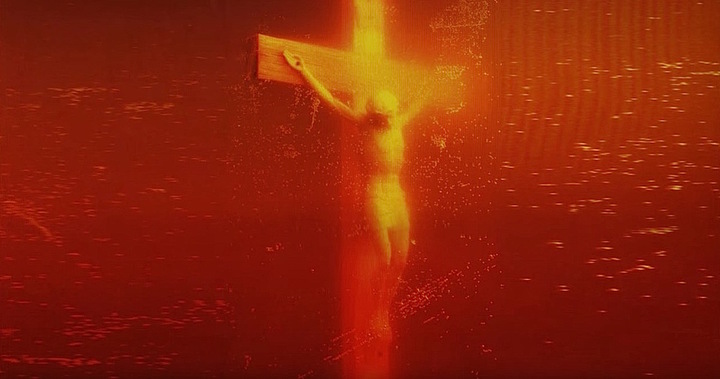

Among religious people, mental shifts are only made by reinterpreting the holy texts and, in this scenario, developing a theology of the Other, which involves seeing God’s face in strangers. An example of how this kind of dialogue can begin, taken from within the Christian tradition, involves that of those Christians who seek to censor or attack Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ on the basis of blasphemy. Such views cannot be countered or changed by arguments in the public square about the value of free speech, as free speech is viewed as a license for blasphemy. In this context, liberal arguments about free speech simply reinforce the religious sense of being under attack. However, it is possible to engage in a debate, based on Christian language and doctrine, about the nature of Christ’s incarnation of which, by submerging an image of Christ in human detritus, Piss Christ actually enables profound Christian reflection. Engaging in this dialogue on these terms, therefore, holds potential for the shifting of perspectives and understandings.

Another example, from outside the field of the Arts, is that of the At Our Mothers’ Feet campaign which worked to raise awareness about the problem of global maternal death amongst UK Muslim communities and inspire them to take action to share learning and to support Muslim NGOs to work on maternal health. It did so by a direct discussion of issues with Islamic scholars in order to explore how issues and approaches could be understood and communicated within an Islamic framework. Following this groundwork, support for public statements was expressed via mosques and media leading to over 50 ulama’ and leaders pledging their support for maternal health and 14 Muslim charities committing to increased work on maternal health.

The radical response to radicalisation, therefore, is to practice the liberal values of inclusion and equality by showing support for the mainstream majorities whose practice of their religion is peaceful and who can speak to others within their religion in the language of their religion. Wider society can support such debates and discussions, as did DfID in the example of the At Our Mothers’ Feet campaign, by seeking out those artists and critics having or wanting to engage in these ways with their faith and providing them with platforms from which their images, voices, and reflections can be seen and heard.

In 2016 St Stephen Walbrook took part in Stations2016[iii], a unique exhibition held in 14 locations across London, which used works of art to tell the story of the Passion in a new way, for people of different faiths. The exhibition was organised by its co-Curators, Dr Aaron Rosen and Terry Duffy, with Coexist House, which aims to create the world’s leading and most innovative visitors centre for learning about religions in the heart of London, celebrating the diversity of the world’s faiths, engaging the public’s imagination, and building understanding and respect. Artists involved included Christians, Jews, Muslims, and atheists. Instead of easy answers, these Stations aimed to provoke the passions: artistically, spiritually, and politically.

At St Stephen Walbrook, we hosted Michael Takeo Magruder’s Lamentation for the Forsaken, 2016 in which Takeo offers a lamentation not only for the forsaken Christ but others who have felt his acute pain of abandonment, in particular, Syrians who have passed away in the present conflict, by weaving their names and images into a contemporary Shroud of Turin. Lamentation for the Forsaken reminded us that the real miracle is our capacity to look into the eyes of the forsaken, and see God. So we prayed, Lord Jesus, enwrapped in death, upon the cloth that bound you was impressed your face, the face of the Son of the living God. Grant us the courage to seek your kingdom amidst the forsaken.

It is such language and such prayers which are required in response to the global challenges that we will face in 2017.

Words: Revd Jonathan Evens, Priest-in-charge St Stephen Walbrook and Associate Vicar, Partnership Development, St Martin-in-the-Fields

Images: Andres Serrano – Piss Christ – Photography Courtesy of the artist – Insert: UNESCO World Heritage Site – Aleppo’s World Heritage site in danger. Courtesy UNESCO

[i] http://www.rabbisacks.org/rabbi-sacks-on-the-open-mind-series-on-pbs/.

[ii] J. Sacks, Not in God’s Name: Confronting Religious Violence, Penguin Random House, 2015.

[iii] http://www.coexisthouse.org.uk/stations2016.html