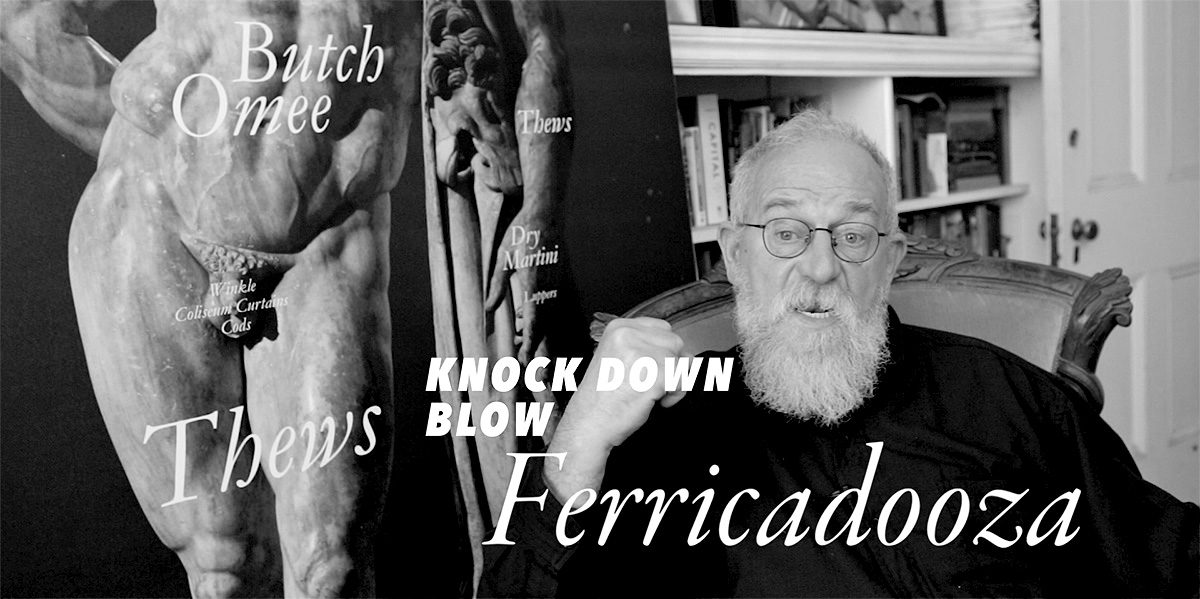

Bruce Eves was awarded Canada’s 2018 Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts. His remarkable story as a practising artist, global facilitator and Programme Director for CEAC (Centre for Experimental Art and Communication) in Toronto in the 1970s is told in a new film by the experimental filmmaker Peter Dudar who also conducted this in-depth interview.

HOW DID THE FILM COME ABOUT?

BRUCE: I’d written an autobiography and asked Peter for feedback . . .

PETER: And I said, “we can make a film out of this.”

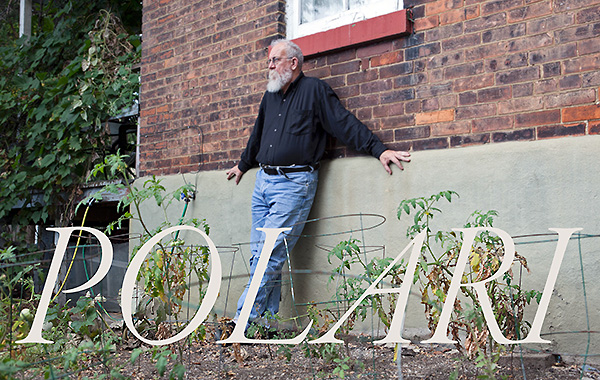

WHAT’S POLARI?

BRUCE: Polari was an “anti-language” created by gay men in London in the 1930s, and is recognised by the United Nations as threatened with extinction. It’s an amalgam of lingua franca, Italian, Romany, rhyming slang, back-slang, obscure words from Shakespeare and phrases from the criminal underground. Polari allowed initiates to speak freely in an environment fraught with danger. It peaked in the 1950s but fell out of favour with the advent of gay liberation. However, in the 1990s there was a revival of interest in Polari as a cultural artefact—something subversive and potentially revolutionary. . .

PETER: I came up with the title very early, and it stuck. I knew I was going to end on Bruce’s Hercules Polari piece. So once I had Polari at both ends of the film, it was a natural progression to reference it throughout. A lot of Bruce’s work references code, and as code, Polari is edgy, witty and subversive, so it’s a natural fit with everything Bruce does.

BRUCE IS STARTLINGLY CANDID.

PETER: Artists are usually protective of their careers in public, and films about contemporary artists usually tread carefully. There’s no risk in saying that Michelangelo had issues with the Pope. It’s another thing to express disdain for someone who can still fuck you over.

HOW WOULD YOU DEFINE ARTIST?

BRUCE: When I was 19, I opted for Art School rather than Archaeology. Though conceptual art ruled, the school still emphasised art history. And as I developed artistically, much of my work dealt with history (personal history, gay history, art history) as well as archiving—and how these intersected with activism. So in a way, I ended up being an archaeologist of a sort after all.

Very soon after school I became involved with the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication (CEAC) and was subsequently hired as assistant programming director.

WHY DID YOU CALL JOSEPH BEUYS A NAZI?

BRUCE: A cursory web search reveals him to have been not only a Nazi but a rather hard-core one at that. Even after being severely wounded, Beuys opted to be patched up and sent back into battle.

I’m shocked that my comment would raise eyebrows because Beuys never hid his past, nor as far as I know, ever expressed any kind of remorse. What I am surprised by is the Pollyanna view that “artist” and “really bad guy” can’t go together. Not only was Beuys a card-carrying Nazi—but maybe what’s worse, is that for the rest of his life he remained a Class-A asshole.

And when he kissed me, he really sucked . . .

PETER: Bruce can separate the person from the work. He’s tough on Karl Ove Knausgaard in the film, but he’s also read more Knausgaard than anyone I know.

Bruce is very articulate about his work – there are no third-party voiceovers in the film. His works have clear intellectual premises, and Bruce knows precisely how they fit into contemporary culture and art history. He never resorts to artspeak.

The film is sometimes uncomfortably honest, and of course, it will make certain art insiders livid. That also makes it fun to watch.

BRUCE: I suspect gallerists hate artspeak because they’re forced to translate it into plain English for their clients. But let’s face it, artspeak is just bad writing. Lazy writing. Behind all of the obfuscation, there is . . . Nothing.

HOW DID YOU FINANCE THE FILM?

PETER: We didn’t. Ask anyone who works in film whether two people can produce a sophisticated feature documentary with no money whatsoever and they’ll say it’s impossible. The fact that it exists is a miracle.

THE FILM IS ALIVE WITH GRAPHICS . . .

PETER: I’m also an art director.

As a director/editor I had to figure out how a viewer perceives one of Bruce’s works at first glance, and then work out how to progress, without repeating myself, to a full reveal.

WHAT CAN YOU SAY ABOUT BRUCE’S HOUSE?

PETER: It’s an all-encompassing artwork—a late-Victorian house that’s partly preserved, partly restored and partly in ruin. It’s filled with Bruce’s unique art collection. We did 20-something setups in this location alone—and they’re all strikingly different.

BRUCE CONTENDS THAT ARTISTIC INNOVATION ENDED IN THE 1970s.

PETER: Bruce and I are consistent on that. We were both performance artists. But by the 1980s there was an international consensus that performance art itself was finished. We were already done with it anyway.

Bruce was anticipatory, ahead of the curve: his last European performances focused on the premise that performance art was a failure and soon after it was truly dead.

PETER, YOU ARE AN EXPERIMENTAL FILMMAKER. “BRUCE EVES IN POLARI” IS BEING DISTRIBUTED AS A DOCUMENTARY.

PETER: It’s being perceived as an innovative documentary, rather than an experimental documentary, which is fine with me. The film is my concept, and it’s still identifiably my work. And even so, it faithfully incorporates Bruce’s work.

HOW DID YOU GET SUCH A RICH PORTRAYAL?

PETER: Bruce trusted me. The result is in-depth.

BRUCE: I only asked that he not to make to look too ugly or sound too stupid . . . is that being shallow? (laughs)

PETER: Bruce has a tough exterior, but there are some vulnerable moments in the film. He breaks down at one point when trying to quote Mary Warnock on the conflicting need to forget versus the need to remember. I teared-up repeatedly when editing the scene.

BRUCE: I wonder maybe if that quote isn’t the heart of the film. She said, “The only way to cope with life is to learn what to forget; the only way to feel one has an identity is to remember.”

OF COURSE, THERE ARE GALLERY SEQUENCES . . .

PETER: I showed Bruce scrounging around a chaotic storeroom for a lost piece, with a voiceover about the loss of his husband, John Hammond.

And I filmed Bruce walking the life-size panel of naked Hercules from the printer to his house—the passersby in the street liked Hercules a lot, but not for aesthetic reasons.

BRUCE: People were ogling and hooting and honking. My neighbourhood usually is very prim and proper . . . (laughs)

JOHN IS A BIT ENIGMATIC, BUT HAS A PRESENCE THROUGHOUT THE FILM . . .

BRUCE: I went to New York in 1978 but was ready to come back after six months, I hated it so much there. Then I met John Hammond . . . Twenty years later he came around to my way of thinking—partly because everyone had died (This is not hyperbole). So we crossed into Canada on May 31st, 2001; got married on our 25th anniversary in March 2004. He was dead six months later after cancer paid a visit.

The film reveals a gift left for me by my so-called in-laws that are shocking in its naked cruelty.

John was my best critic and would always encourage me to do my worst (laugh). And . . . I still think about him every day.

THERE’S A LOT OF AGITPROP IN THE NYC PARTS.

BRUCE: John and I were called to rescue the early organisation records of the Gay Activist Alliance . . . And it just grew from there into the International Gay History Archive—against the backdrop the AIDS epidemic. (The archive is now housed in the Rare Books and Manuscript division of the New York Public Library).

Art-making struck me as trivial given what else was going on; but I accepted a commission by Artists Space to do an installation about the AIDS epidemic, as part of an ongoing series. I took a completely opposite approach to everyone else and lambasted everyone involved with the epidemic for their careerism, and profiteering, and . . . Well, this landed like a bomb. At the opening, all these rich people were thinking of themselves as just soooooo progressive with their red ribbons, and here I was shitting on their feet. The gallery’s AIDS series was immediately cancelled and the curator summarily fired.

PETER: I did use one image twice. And that’s the iconic “Silence = Death” poster. It’s a near perfect melding of design and message. The second time I showed it, I morphed the “Silence = Death” text into “AZT = Death”, which was Bruce’s incendiary appropriation of the phrase for that show.

BRUCE: That installation was very much about the NOW. In the early-2000s I stumbled upon a text that I’d completely forgotten about in the CEAC archives at York University in Toronto. It was two diary entries from 1977 chronicling a couple of nights at my favourite gay bar—the Parkside Tavern. I paired the text with a picture of two guys fucking with a line across the middle stating “things were better when everyone hated us”. That piece is the flip side of the Artists Space installation—it deals with the THEN in relation to the NOW. It also landed like a bomb (but in the good way). There was almost a fist fight over the audacity of someone suggesting the past might possibly have been better. The film has a very funny commentary between the owner of the piece and me.

These works are directly informed by the gay archive. They’re activist, I guess.

AND THEN THERE WAS PUNK ROCK . . .

PETER: CEAC housed the Crash ‘n Burn venue in their basement in the summer of 1977. A Toronto band, The Diodes, managed the place.

BRUCE: It couldn’t last. Crash ‘n Burn operated on one-time party permits, so the city was wising up to the scam. There were only one toilet and no fire exits, Renovating it into something legal would have been impossible.

PETER: Bruce goes into the legendary status of “Raw/War”, a 45 RPM record he did with The Diodes and another band, The Curse—you can decide for yourself how that worked out when you see the film.

BRUCE: The record ended up in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, as well as the University of Bologna. I’ve never made a single red cent from the thing . . . (laughs)

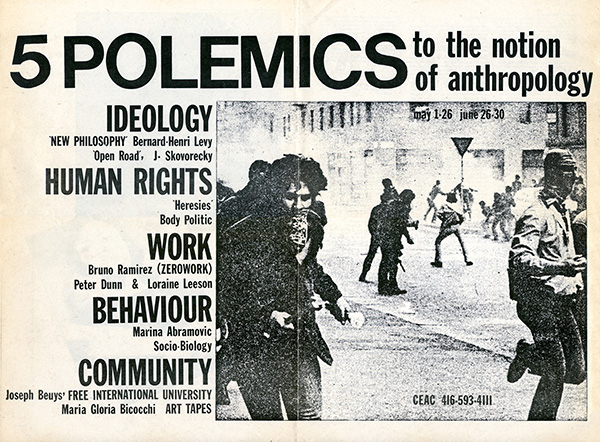

CEAC’S LAST EVENT WAS A SEMINAR SERIES.

PETER: There was some consensus that seminars integrating art, politics and everything else were the new wave of post-performance. The “Five Polemics to the Notion of Anthropology” series had everyone from philosopher Bernard Henri Levy to performance artist Marina Abramovic . . .

BRUCE: Oh her! The Olympic Marathon-Sitting Gold Medal winner you mean! She tried to get our friend and colleague Lily Eng disinvited from Documenta so she’d be the only performance artist present. She’s a total horror. . . .

AND THEN THERE IS HERCULES . . .

BRUCE: I picked the “Farnese Hercules” on purpose. He has not one single hint of effeminacy; He’s “the omee of omees, he’s the man of men” (laughing), and by tossing all these faggy-sounding words over the top of this he-man I’m making fun of this type of masculinity. Gay-baiting him in a way . . .

IS HERCULES APPROPRIATED?…

PETER: It’s not brainless appropriation. By linking ancient art and the twentieth-century development of Polari to current sexual politics, Bruce is creating a very interesting bridge to the contemporary world.

CAN YOU SAY SOMETHING CONCISE ABOUT THE THEMATIC ARC OF THE FILM?

PETER: The film starts on a high, as Bruce’s younger self-scores successive art world triumphs. His work is cutting-edge, anticipatory. Then there’s a middle period when he’s immersed in personal tragedies and his art flounders. But he doesn’t stand still; he addresses ‘Armageddon’ by becoming an archivist. Then his work starts to focus on his personal tragedies, and maybe therapeutically pro-vides an entry back into the wider art world. In the end, we see a reinvigorated artist producing more innovative and challenging work than ever and maybe, and it’s a big maybe, goading or inspiring others out of complacency.

“BRUCE EVES IN POLARI” is an up-close and personal portrait of Bruce Eves, the 2018 winner of Canada’s Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts –Canada’s highest honour. Eves’ work has remarkable intrinsic value that also engages key aspects of culture and history. His story began in Toronto’s clique-driven avant-garde art scene in the mid-1970s. As practising artist and Programming Director for CEAC (Centre for Experimental Art and Communication), among other activities, Eves crafted socially-engaged performance art pieces that were shown throughout North America and Western and Eastern Europe, including a stint with Joseph Beuys at Documenta VI. He was at the forefront of marketing cutting-edge Canadian art internationally. Eves created and curated the International Gay History Archive at the point when the AIDS epidemic threatened a loss of history and is now housed in the Rare Books and Manuscript division of the New York Public Library.

Eves’ work evolved into photo-based and installation works. The use of coded language is a recurring theme in Eves’ practice that addresses political and personal issues in startlingly original ways. Eves’ dialogue in the film, though sophisticated, is very entertaining and blessedly free of jargon. A recent series of works based on Polari – an underground vocabulary invented by gay men in early to mid-20th century London is referenced throughout the film (often quite humorously). Consequently “Bruce Eves in Polari” engages not just the intellect, but is also sensual, and runs the whole gamut of emotions from laugh-out-loud funny to deeply raw, crushing sadness.

The film was conceived and directed by Peter Dudar. Dudar shares a lifetime of experience within the same arts culture as Eves. Dudar’s filmic style is dynamic and highly original and has been awarded for his “arresting cinematic composition and elegant study of movement” in dealing with straightforward images, but the film is also graphically stunning. Dudar is also an accomplished designer in print and electronic media and brings the film’s myriad photos and graphics fully to life. He fully energises Eves’ works visually, while ingeniously disclosing their meaning. Dudar’s integration of image and text, which has been called “absolutely brilliant” in his previous work, is at its most advanced here, deepening the shared contexts of both.

“Bruce Eves in Polari” is witty, poignant, and unflinchingly honest. For anyone interested in a fresh approach to the cultural politics of the last half-century, it is a must-see

Words/Photos © Bruce Eves and Peter Dudar First published Artlyst © 2018

Polari: conceived and directed by Peter Dudar with Bruce Eves will be released in 2019