When I first went to visit Chuck Close in his studio in 2004, I was in awe of him. But he was easy to talk with so that soon wore off. I had seen him at many exhibition openings over several years in New York. In his wheelchair, he was hard to miss. I always thought – how brave. I didn’t know then what health struggles he had for much of his life.

I’m interested in the artificiality of marks and most of my marks are very abstract – Chuck Close

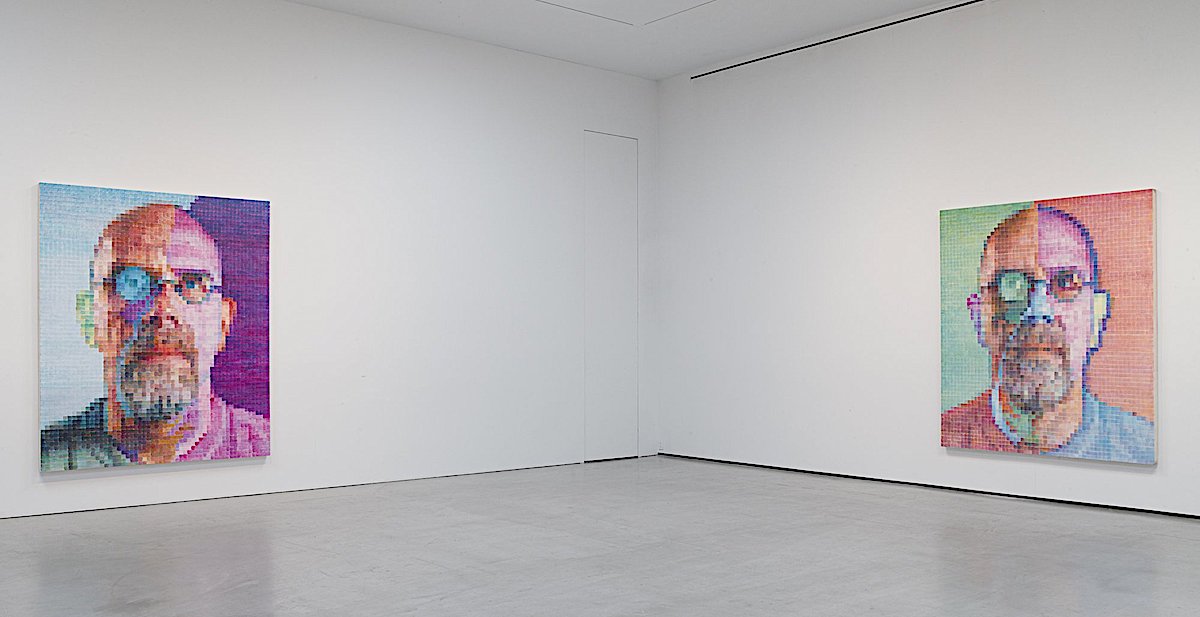

His studio in the East Village was also distinctive in that it had a huge “easel” which wound up and down and went into the floor, so he could move it easily to reach the little square in front of him that he was focusing on. He always worked in meticulous detail in a time-consuming way so that a canvas could take a year. His subject was portraiture, always based on photographs of friends, never from life. He squared up and transferred the photo via a conventional grid. The results were thrilling, revolutionary, sensational.

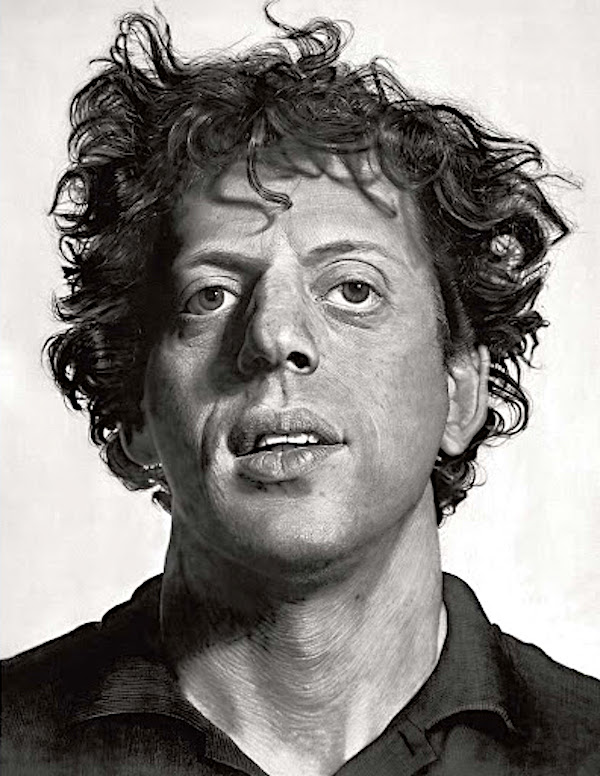

He came to fame in 1970 with a series of these 9ft high mesmerising, monumental hyper-realist portraits, like the famous one of composer Philip Glass showed every pore and hair. Close acknowledged that Glass was to him ‘what haystacks were to Monet’ – variations on a theme. “I loved his Medusa curls.”

He told me, “Basically, I wanted to make a picture that was big, aggressive, confrontational, knocked-your-socks-off images with teeny little marks, images where the face becomes a sort of landscape where you stumble over a beard hair. ”

In 1988 at the age of 48, Close suffered a collapsed spinal artery that left much of his body paralysed. Through rehabilitation, he got back his ability to paint by using a brush-holding device strapped to his wrist and forearm. As someone commented after his death this week, “Chuck so heroically rebounded from his health crisis, I figured he was immortal.”

Close is often called a realist, even a super-realist. He did not like the term, because ‘I’m also as interested in the artificiality of marks and most of my marks are very abstract. From the start, my tiny squares were always full of stuff – dots, stars, slashes and lines. As the grid got bigger and more complex, each one of those mosaic squares alone was a miniature abstract painting in its own right. Yet there is a specific to my calligraphy of the squares, which is absent from abstraction.”

His calligraphy included dazzling sunbursts of scrawled noughts and crosses, some gleeful hotdog or doughnut-shaped, “You can tell I’m always hungry”, he told me, laughing. Yet when viewed from a distance, these individual squiggles and pixilated doughnuts magically, miraculously, resolve into a surprisingly realistic face.

He was not a purist. “I’ll switch horses in midstream to a different medium if it will make a better image.” In the 1970s, he used monochrome but then moved into extravagant colour. “I have always gone back-and-forth. I really like black and white. I like things of a graphic nature and if I’m working in monochrome, when I go outside, I see everything in shades of grey. But once I’ve squeezed a tube of yellow or crimson, I realise again how terrific celebratory colour is.”

In the 1980s, these pixilated and majestic heads were sometimes made via Japanese-style woodcut, others in paper pulp – laborious, labour-intensive, exacting work. Digital technology was a long way off.

But, a passionate printmaker all his life; by 2012, he was using technology via collaborations with experts. More than 10,000 of Close’s hand-painted marks were scanned into a computer and then digitally rearranged and layered by the artist using his signature grid. These works were Close’s first major foray into digital imagery. Close himself said, “It’s amazing how precise a computer can be working with light, colour and water.”

In a 2014 interview, Close talked about Joe Wilfer – who, back in 1983, helped me with my ‘New Scottish Prints’ exhibition for Britain Salutes New York in New York. Close said, “I’ve had two great collaborators in the God knows how many years I’ve been making prints. One was the late Joe Wilfer. Now I’m working with Don Farnsworth at Magnolia Editions. These are the most important collaborations of my life as an artist.”

Before, Close used to make every mark, draw every line, himself. “I like to make every decision. Sometimes it’s hard to believe I made those etchings without a computer program to digitalise the tones and values.”

He believed in making art the old-fashioned way, very much by hand. This ethos came from his grandmother, who was always knitting or crocheting. He liked working in serial fashion. “It frees you from artist’s block. I don’t wait for the clouds to part. Inspiration is for amateurs.’

The logistics of Close’s printmaking were incredible. He is big prints are 12 feet long. Some portraits use 150 different silkscreens, while his black-and-white 1988 self-portrait needed 6800 squares of hand-applied acid. He was often pushing techniques to the limit. “I’ve always been an artist looking for trouble,” he told me. Prints have moved me forward more than anything else. It’s too easy to just keep plodding along, cracking those suckers out. Lazy thinking. That’s not good. But then I’ve had some rocks put in my shoes,’ he joked, referring to his disability.

Close was always happy to explain his processes, chronicle his failures and admit his errors. He did this in his extensive 2004 retrospective at New York’s Met Museum. “This exhibition also shows you how art gets made. A lot of people don’t know.”

“Painting is the perfect medium and photography is the perfect source because they have already translated three dimensions into something flat. I can just affect the translation.” Thus he has dissected the human face of such luminaries as President Bill Clinton, Lou Reed, Cindy Sherman, Kiki Smith, and – often- in self-portraits of himself.

There’s an irony to Close’s pictures of friends like Glass, Richard Serra, Alex Katz, Lucas Samaras, Nancy Graves. Close wanted anonymous people so picked his friends, but all became famous! He also painted them straight on, like a mug shot or passport photo. Why a life of portraits, I asked? “I care more about people than anything else. I want you to care about them and care about the image.” Why so many self-portraits? “We are all narcissistic. But it demonstrates that I may not flatter others, but neither do I flatter myself.”

In 2000 Close received the National Medal of the Arts from President Clinton. in 2010 he was appointed by Obama to the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities, resigning in 2017 as ignoring ‘Trump’s hateful rhetoric would have made us complicit in your words and actions.” Recently his 2000 sq foot mosaic was installed at Manhattan’s 86th Street subway station.

Chuck Close born 1940, died August 19th 2021. He was married twice and leaves two daughters.