The third piece in my series of conversations with new graphic novelists and comic artists is with Mark Stafford. As with many ‘fine artists’ (whatever this means!) turning to illustration in recent years to inform their work, I feel that some of these artists are looking back to previous practice rather than interacting with the current developments that are redefining the practice of comic panels, or graphic memoir or illustrated book. I wanted to talk to some artists who were creating exciting work right now in the field of visual narrative story for the bookshop or the comic website. This second interview is with Mark Stafford, one of the most respected of contemporary cartoonists and graphic narrative artists. He is Cartoonist in Residence at the Cartoon Museum in Fitzrovia. His bibliography is more than impressive and his art projects include collaboration with the British Council and Arts Council Korea on a comics project with the Kangkangee Arts Village in Busan, South Korea 2018. He was in conversation with me earlier this year about HP Lovecraft and more for Resonance FM (The News Agents, Sat 2.30 pm-3.30 pm). You can find the show on Mixcloud:

Books; Graphic Novels: The Bad Bad Place, Lip Hook, The Man Who Laughs (with David Hine) Cherubs! (with Bryan Talbot)Anthologies: The Golden Thread, The Broken Frontier Anthology (with DH,) The Mammoth Book of Skulls, The HOAX Project, The Lovecraft Anthology Volume One (with DH,) The End

JCM: How do you feel your art style ‘fits’ into what is happening in the graphic novel scene right now in the UK and beyond. What styles do you think have had a direct influence on the way you work?

Mark Stafford: Sometimes, I wonder if I fit in anywhere at all. I think I’m a bit too odd for a lot of commercial gigs, and not art school enough for the ‘risographed onto vintage sugar paper’ mob. I have a niche, I guess. I mean, I’ve got books out, so something must be working. Influence-wise there’s a bit of a battle going on in the work. As a kid, up through my teenage years, I obsessed over artists who had a heightened realistic approach, people who painted and drew weird stuff, but cared about light sources (from Magritte and, De Chirico through to Richard Corben,) but later I kind of fell in love with artists who were more about expressive marks on paper than rendering a well-lit thigh muscle (Grosz, Panter, Doucet,) and I don’t think I’ve properly come down on one side or the other. So I’ll draw something physically impossible and then later find myself attempting to add realistic shading to it in the colouring process. This is insane. But then you look at the work of Jose Munoz and Lorenzo Mattotti and realise there’s a lot of that about. I love it all too much, I think. I can’t let it go. I can’t settle…

JCM: What do you think works about your style? Do you think you have a style? How would you describe it? Would you describe it?

Mark Stafford: My stock answer for questions about this stuff is that style is not something you chase after, it’s something you end up with. Over the years you make a bunch of decisions about how you’re going to render things and solve problems, and some of those don’t end up working too well, and some of them do, so you drop stuff and carry stuff and eventually you reach an age, where you think… ‘Well, I guess I draw like this now.’

I like ink, and I like drawings that revel in their inkiness, dip pen and dry brush and trying to get the most expressive lines and marks you can out of the materials to hand. That part of the process is where I’m happiest. That’s a constant. But it’s an ongoing thing; I chafe against my limitations and ingrained tendencies a bit. I don’t want everything to be so cramped and diseased. I want there to be more of a sense of space. I want to stop drawing such goofy looking hands. It never stops. Occasionally you think- ‘Hey, that look of distress I’ve rendered on that child’s face is really working,’ Or ‘you picked a nice shade of brown for that died bloodstain,’ but it’s all fleeting.

JCM: You have moved between non-digital and digital media as an engine of expression and your comic presentation for many years. Can you tell me something about what you’re doing now and your evolution as an artist to get to this point?

Mark Stafford: I’m not sure technology likes me, but I’ve come to an accommodation with it. I spent years drawing straight to ink and then weeping because the composition was all to cock. At a certain point, working on my first book I had to embrace the fact that the ability to move my drawings about a bit and shrink elements and arrange others was a blessing that was going to save me from some kind of breakdown. So, I draw pencils; I scan the pencils, I size and correct and arrange everything in Photoshop, then I print that out in light blue on bristol board and then ink those blues on the board. Then I scan the inks and go back to photoshop to colour and prepare for print. That’s my process now. There’s technology involved, I have a Wacom tablet, but I generally draw on paper and am only using photoshop 7, which adobe gave to the world in —-. I also use digital photography to add textures in the colouring process; there are close up photos of rust or lichen or rotten wood hidden in the layers. If you’re walking with me be prepared to stop every now and then as I take a shot of a knackered bench or a stagnant pond. That’s going to be part of an apocalyptic vista. Trust me.

JCM: Can you tell me something about how the relationship between panel and narrative works in a couple of specific instances in your work. What do you select for panels and how does that embed in or build up a longer story.

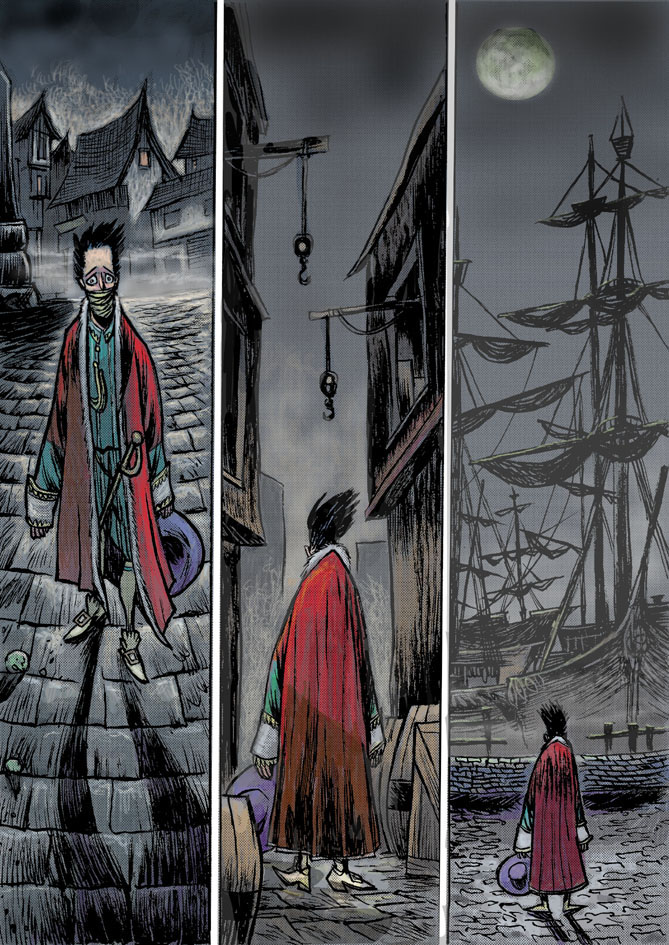

Mark Stafford: It’s instinctive now, but it took me an embarrassingly long time to realise that this was the heart of comics, the bit of the art form that wasn’t quite like any others, not writing or drawing but arranging sequential images and text so that they flow off the page and into the reader’s skull. I like these two pages from myself and David Hine’s Hugo adaptation The Man Who Laughs. The first (shown here without lettering,) shows Gwynplaine, a man mutilated as a child so that he wears a grotesque, permanent grin, waking up in a palace, after a life spent in abject poverty, never having slept anywhere other than a caravan. I like how the three top inset panels increase in size as he wakes and lead your eye rightwards and down so that you have to adjust to the main image, moving back left to the shocked, now awake Gwymplaine dwarfed by the surrounding weird splendour, off-centre and unbalanced The second is a silent page showing our hero after his world has fallen apart. He has lost everything, in three vertical panels, as he drifts towards the waiting waters of the Thames. I’ve added to his sense of isolation and despair by having him shrink and descend from panel to panel. The Man Who Laughs was the first long-form work I had created from my own layouts and I delighted in discovering this kind of stuff, the grammar of comics, as it were.

JCM: Do you think that this is an important time to be conscious of putting our own lives into our comics rather than attempt to tell stories from other points of view.

Mark Stafford: Well, it’s always going to be preferable to try to relate some kind of human truth in your work rather than the endless recycling of genre tropes that makes up 90% of the comics the general public sees. That said, given a choice, I think I prefer the generation of cartoonists who made-up characters and told stories (Dan Clowes, Los Bros Hernandez, Charles Burns) to the generations since who have become more and more directly autobiographical. Partly because a lot of cartoonists tend to come from similar backgrounds and lead similar lives, at least in the west, and there’s a limit to how many stories you want to hear about crappy flatshares and crappy jobs and crappy first relationships from overeducated middle-class agoraphobics. It’s ink and paper, you can do anything, and your life is going to sneak in there anyway, so go nuts. I do short strips detailing life experiences now and then, but just as much of my life ended up in Lip Hook, which is notionally a weird horror/crime tale. There are a few more substantial stories from my life that I think are worth relating, but I’m not sure I have the right tools yet. I like the approach Rachael Ball took in The Inflatable Woman, where she took her experiences with breast cancer and made them into something strange and new and all the more moving for not being so prosaic.

JCM: I personally think that Sci-Fi and fantasy genre are very important right now as means of expression. Can you say something about these genres in your own work and that of a couple of other comic artists / graphic novelists?

Mark Stafford: Some have opined that you need to be careful what you summon into the world, we seemed to revel in decades of dystopias and now look at the state of us. I grew up with Star Wars and 2000ad and read a ton of SF books as a teen, but largely dropped out of love with it all because fantasy fiction tends towards the baggy and endless, whereas I grew to prefer the well constructed and self-contained. I like the SF of weird ideas thought through to conclusions between two covers, and have an aversion to the word ‘trilogy.’ Also, I couldn’t stand all those sodding elves and moody buggers with swords.

Recently though, I’ve been rediscovering the weird fiction of the early 20thC (Machen, Blackwood, Lovecraft etc.,) in which repressed academical types are horribly destroyed by forces beyond human understanding, and it speaks to my repressed, academical heart, as we’re all horribly destroyed by socio-economic forces beyond anybody’s apparent control.

My favourite cartoonists of the weird would be Charles Burns and Junji Ito, both obsessive renderers, to wildly different effect. Gou Tanabe and Alberto Breccia have both delivered jaw-dropping versions of Lovecraft sources, and the king of science fiction design, truest to my teenage dreams would be Moebius (Jean Giraud) a master of line and colour and form. His writing drifted way into hippy new age territory for decades, though, so you have to put up with a lot of bloody crystals.

JCM: Are you using any digital comic outlets or mostly sticking to physical media. Do you see a shift towards digital speeding up right now? Any thoughts on that?

Mark Stafford: When I was in Korea for the British Council gig that ended up as Kangkangee Blues I grew to realise the extent that webtoons were the medium over there, and that you had to seek out the print versions in selected cafes and shops. Webtoons, (story apps whereby you swipe on your phone from panel to panel,) are intriguing to me. Though obviously, you lose a lot of storytelling tools with the loss of page design and panel layout there are probably compensations which would be clear the more you played with the form. I’ve not done much yet, barring my contribution to a COMICA show at the ICA years back as part of a huge wall-sized strip by many contributors that could be read in many directions and made most sense online.

Most cartoonists I know are print-focused, partly due to tradition and nostalgia but also the page design element which is a massive part of the grammar of comics, and that no digital device I’ve seen elegantly delivers. But I hope webtoon avenues are being explored, The Korean model makes so much more sense, in terms of distribution and compensation for artists, than the archaic mess we’re living through. A brave new art form really needs brave new comics, though. You first.

JCM: A question about story – I know you, like me, grew up with a lot of horror/folk horror both in television and book form. Any thoughts on particular stories or figures in narrative from this tradition that has been influential on you? How do you deal with horror from different cultural sources and the connection between horror and religion, e.g. pagan versus Christian?

Mark Stafford: I went to a C of E primary school as a child in Christchurch, Dorset, which meant spending a fair amount of time in the Priory, a church built through the various stages of mediaeval architecture, and I still remember that feeling of ancient stone and ritual and endless symbols my tiny brain couldn’t understand. I don’t get religion, really, I can understand the search for the transcendent, for acceptance of that which is above and beyond us, for the solace of tradition and ritual in the face of grief, but I don’t understand anyone bowing down before the parade of arseholes and charlatans who peddle horrible politics in the guise of sacred truth. I think that’s why I like religious tat, all those chipped plaster of Paris saints and plastic madonnas. “Here’s the eternal truth of the world beyond, we’ve made it out of fun fur and polystyrene.”

My sketchbooks are full of devils and gods and monsters. Alongside the gospels, there was always that childhood fear of playground rumours and beasts in the woods and nobody quite telling you what the hell morris dancers were up to. All of this ended up in Lip Hook, our’ tale of rural unease,’ of course, but I’ve been looking at old Japanese yokai drawings recently and wondering if I could do the same for the odd imagery of British legend. I’ve had a go at Black Shuck. More may follow

JCM: Do you think any of us will ever escape our bedrooms now the real world has turned out to be the biggest horror show of all?

Mark Stafford: I bloody hope so, I’ve spent a lot of my life going nowhere, so to speak, and only recently had the opportunity, through my work, to get out and about a bit. Now, for months, I’ve barely gone further than the park around the corner. Cabin fever has truly set in, and I can’t see a social occasion worth the risk of breaking it. I’ve been fairly productive in that time, but with no shows to go to there’s a lack of focus. UK comics folk generally directed their energies towards launching new books at either Thought Bubble or the Lakes comics festivals. Now both are going digital-only and I don’t know what that means yet.

A lot of people were struggling to survive before COVID 19 made everything that much worse, I was in that boat, and the grim solace I got from my own misery getting an awful lot of company didn’t last that long. All is up in the air, it feels like dice are being rolled, and all you can do is get on with the work to hand, be as social as you can and stay safe.

You are Cartoonist-in-Residence for the Cartoon Museum which is under threat due to COVID. Why should we care, and if we do care, what should we do?

You should care because the noble art of taking the piss, of speaking truth to power through the point of a pen, has been a vital part of Britain’s cultural playground for centuries, and if all that vitriol has to be stored somewhere, then Fitzrovia is as good a place as any. As well as all that heritage and history The Museum is sorely needed as a hub for all things Cartoon happening right now, a place for workshops and discussions and boozy book launches where inky enthusiasts of all persuasions can hang out, buy a book or three and take in a Searle and a Steadman before some suitably themed life drawing or a Q&A with a beloved creator or despicable underground artiste.

COVID has meant that the venue has been shuttered for months now. The plan is currently to reopen in September, but that gap has put a massive hole in the finances. There is a current campaign to raise £150,000 to ensure the place survives, and people can donate here:

For my part, I’m currently creating 50 original pieces of postcard-sized art to be sent out with 50 copies of the latest Hine/Stafford book, The Bad Bad Place that the publisher Soaring Penguin has generously donated towards the cause. You can buy one here, thoMark Staffordugh hopefully they’ll all have been snapped up by the time you’re reading this:

Please donate. The Cartoon Museum really is somewhere special.

Read More About graphic novelists and comic artists

I’m on Instagram/twitter as @marxtafford