In 1974 Michael Craig-Martin exhibited a work entitled An Oak Tree which, through the text alongside a glass of water displayed on a bathroom shelf, claimed that this work is an oak tree in the form of a glass of water. To make this claim Craig-Martin drew on Christian understandings of sacraments which are most fully realised in the Eucharist.

The artist David Jones wrote of the Eucharist as being to do with the re-calling, re-presentation and remembering of an original act and objects in a form that is different from but connected to the original act or object that is being re-called. Remembering the Lord’s Supper is not simply recalling it to mind; instead, it is re-membered by the re-enacting and re-presenting of the original act. The original act is a once-for-all act but it can be re-created and re-presented in Eucharistic celebrations. A different form is used to bring a past act into the present in a way that means Christians encounter, receive and respond to that original act afresh. They are, therefore, doing more than simply recalling that act in their minds but, at the same, are not repeating the act in its original form in the present.

‘Belief underlies our whole experience of art.’

Jones developed an understanding of art which viewed all art as sacramental because the signs made by artists are the thing signified under the forms of their particular art. The artwork is the original object or action that has been re-presented but in a different form meaning that it is both ‘the thing’ and a ‘different thing’ at one and the same time. In the same way as, at the Eucharist, the bread and wine are both simply bread and wine and the body and blood of Christ at one and the same time.

Craig-Martin explained that: ‘I considered that in An Oak Tree I had deconstructed the work of art in such a way as to reveal its single basic and essential element, belief that is the confident faith of the artist in his capacity to speak and the willing faith of the viewer in accepting what he has to say. In other words, belief underlies our whole experience of art.’

‘The ability to believe that an object is something other than its physical appearance indicates requires a transformative vision. This type of seeing (and knowing) is at the heart of conceptual thinking processes, by which intellectual and emotional values are conferred on images and objects.’ Craig-Martin is saying that conceptual art, even art itself, is at its heart about the belief of the artist in re-presenting an object or idea in the form of something other. The artist is, therefore, doing with her or his art what the priest does with the sacraments.

I was reminded of An Oak Tree by the statement, in the exhibition notes for Rose Finn-Kelcey: Life, Belief and Beyond (Modern Art Oxford), that Finn-Kelcey’s ‘finished works often invite a leap of faith as ideas are transformed into images and materials.’ She herself stated that she worked in the belief that she could continue to reinvent herself and remain a perennial beginner. Faith was therefore not just among her recurrent themes but also informed her creative practices, as, Craig-Martin argues, is the case for all artists.

Finn-Kelsey has been described as ‘one of the few contemporary artists to tackle the issue of religion in their art.’[if !supportFootnotes][i][endif] This can be challenged on two fronts; first, by using Craig-Martin’s argument that all conceptual art is at its heart sacramental, and, second, by reviewing the range of artists contemporary to Finn-Kelcey who have also explored aspects of religion, belief or spirituality within their work. In a recent post for Huffington Post about major contemporary artists who have consistently returned to religion as subject matter, as well as to the spiritual/aesthetic experience of making and experiencing works of art, S. Brent Plate produced a shortlist of contemporary artists that included Shahzia Sikander, Anselm Kiefer, Andy Goldsworthy, Ann Hamilton, Atta Kim, Bill Viola, Theaster Gates, Meredith Monk, Sanford Biggers, and James Turrell.[if !supportFootnotes][ii][endif] To these could be added Damien Hirst, Chris Ofili, Robert Rauschenberg, Andres Serrano, Betty Spackman, Sam Taylor-Wood, Paul Thek, Mark Wallinger and Andy Warhol, among others.

Paul Thek is a particular case in point, as this Brooklyn-born, Catholic-raised artist once stated that, “Art is Liturgy, and if the public responds to their sacred character, then I hope I realized my aim, at least at that instance.” He made this comment while in conversation with Swiss art historian and curator Harald Szeemann, when he also named the late-medieval theologian Meister Eckhart and the Holy Scripture as being among his key sources.[if !supportFootnotes][iii][endif]

In 2013 Kolumba, the Museum of the Archdiocese of Cologne which has the largest collection of Thek’s work in the world mounted an exhibition entitled ‘Art is Liturgy’ to explore this claim, as well as the possibility of its opposite – the extent to which liturgy itself might be art. Kolumba’s director Dr. Stefan Kraus said, ‘Liturgy gives a communicable form to belief, allows it to be experienced via the senses, becoming transformed into a reality of its own. This claim to a distinct reality beyond the factual, the rational or even the illustrative is something shared by art and religion.’

‘A sculptor, painter, and one of the first artists to create environments or installations, Paul Thek came to recognition showing his sculpture in New York galleries in the 1960s … At the end of the sixties, Thek left for Europe, where he created extraordinary environments, incorporating elements from art, literature, theater, and religion, often employing fragile and ephemeral substances, including wax and latex.’[if !supportFootnotes][iv][endif]

Thek’s spatial installations ‘brought the viewer into a world full of declarations of faith and Thek’s private mythologies’: ‘The experience of an environment was shaped by a processional progression through different stops, as well as the opportunity to linger in various resting-places.’[if !supportFootnotes][v][endif]

‘The idea of “Procession” lies deep in the heart of all of Thek’s work and life, which were conjoined in an always-evolving experience that was ephemeral or nomadic, unfixed, collaborative, full of ritual, and anti-concrete.'[if !supportFootnotes][vi][endif] ‘In the winter of 1973/74, Paul Thek … was a guest of the Lehmbruck Museum in Duisburg, where he installed the room-filling environment “Ark, Pyramid – Christmas” (“The Manger”)–a development of the legendary “Pyramid” installation realized at Documenta 5 in 1972. This exhibition, organized by the director of the museum at the time, Siegfried Salzmann, was the fourth in Thek’s large-scale projects in Europe, all of which engaged with individualized religious symbols (or what Harald Szeemann termed “Individual Mythologies”). The Christmas season provided Thek with the occasion to present, for the first time, a self-written theater piece in the form of a nativity play featuring children from Duisburg.'[if !supportFootnotes][vii][endif]

As one of the first artists to create environments or installations, though ‘overlooked by much of the American art establishment,’ ‘Thek’s ephemeral installations and collaborative strategies’ continued to inform and influence a generation of younger artists.’[if !supportFootnotes][viii][endif] We can now ‘recognize his influence on contemporary artists ranging from Vito Acconci and Bruce Nauman to Matthew Barney, Mike Kelley, and Paul McCarthy, as well as Kai Althoff, Jonathan Meese, and Thomas Hirschhorn.’[if !supportFootnotes][ix][endif] ‘Thek’s treatment of the body in such works as “Technological Reliquaries,” with their castings and replicas of human body parts, tissue, and bones, both evoke the aura of Christian relics and anticipate the work of Damien Hirst.’

Life, death, and spirituality were also recurrent themes in Rose Finn-Kelcey’s work. Guy Brett notes that many of her later works explored this theme, “among them God Kennel – A Tabernacle (1992); Pearly Gate, Souls and Jolly God (all 1997); God’s Bog (2001); and It Pays to Pray (1999), a work in which contemporary ‘prayers’ were available from chocolate-vending machines mounted outside the Millennium Dome.”[if !supportFootnotes][x][endif]

What can God mean today? What is the spiritual in contemporary society, and where can it be found? Brett suggests that “Finn-Kelcey responded to such questions with a complex mixture of reverence and satire, debunking and venerating, in ways that have lost none of their capacity to surprise.”

Like Thek, Finn-Kelcey was “brought up in a family that was quite religious.” Religion, she said, “was quite a big part of my life.” While it was something she felt ambivalent about she was also at the same time very conscious of wanting to explore “the spiritual located in the ordinary.” In 1999 It Pays to Pray was commissioned for the Millennium Dome Project and ‘she customised chocolate vending machines to produce, on payment of 20p, prayers instead of chocolate!’ Bounty, Starbar, Timeout, Wispa – were all taken as titles for prayers. ‘The idea of indulging our craving for comfort but receiving instead a prayer gives us food for thought.’ The prayers were delivered digitally by the machines’ L.E.D. screens. ‘With a final twist and after the prayer is consumed, the 20p coin is then returned to the purchaser.’[if !supportFootnotes][xi][endif] As Finn-Kelcey explained, ‘The work plays on the accepted orthodoxy that chocolate is associated with happiness through a chemical change/charge and that people use vending machines for a quick “fix”. Many of the brand names reflect the customers’ desire to be uplifted or transported elsewhere. I aim to make the text mischievous, challenging, plausible, ironic, with a level of truth.’[if !supportFootnotes][xii][endif]

Angel was: ‘A glittering mural composed of over 85,000 coloured, metallic shimmer-discs … hung over the prominent west façade of St Paul’s Church in East London. The image represents an angel, created using ‘emoticons’, or ‘text speak’ – the language of letters and punctuation marks used in mobile phone texting. In this case, a colon, dash, bracket, and zero formed a smiling face with a halo. Each shimmer-disc was hand mounted onto large advertising hoardings and left to move independently in the wind, causing the surface to ripple and move throughout the day.’[if !supportFootnotes][xiii][endif]

Sally O’Reilly wrote that with this work, Finn-Kelcey seemed ‘to be emphasising the sweet pathos of art making, the difficulty of finding the eloquence to voice the unvoicable, the absurdity of evoking the spiritual from the material.’ Yet, she suggests, ‘this Angel is resurrected by the forces of nature which, whether or not you believe in their provenance from God, are undeniably ethereal, impossible to fabricate.’[if !supportFootnotes][xiv][endif]

Duncan Ross, the Vicar of St Paul’s Church, reflecting on the impact of this work locally, and the congregations/audiences of churches and art galleries, said that: ‘What public art did for us is what both church and art must constantly seek to do; to engage with those who are NOT the ‘usual suspects’ and to engage honestly and respectfully outside the safety of the sacred space – the sacred space of the gallery or of the church.

For once, people in our community felt that there was something affirming of them in their midst. A creative affirmation which only such a work of public art could convey.’

The work of Finn-Kelcey and Thek demonstrates that conceptual art is sacramental because conceptual artists re-call, re-present, re-enact and re-member the things signified (whether angel or oak tree) under the forms of their particular art. So, vending machines become vehicles for prayer and an installation becomes The Nativity. Their work also demonstrates that conceptual art is liturgical as conceptual artists create installations that give communicable form to belief allowing it to be experienced via the senses; those who NOT the ‘usual suspects’ pray and respond to angels and become part of The Nativity.

As Craig-Martin suggests belief underlies our whole experience of art because it is the confident faith of the artist in his/her capacity to speak and the willing faith of the viewer in accepting what s/he has to say. This is to say that the finished works of conceptual artists, such as Finn-Kelcey and Thek, invite a leap of faith as ideas are transformed into images and materials.

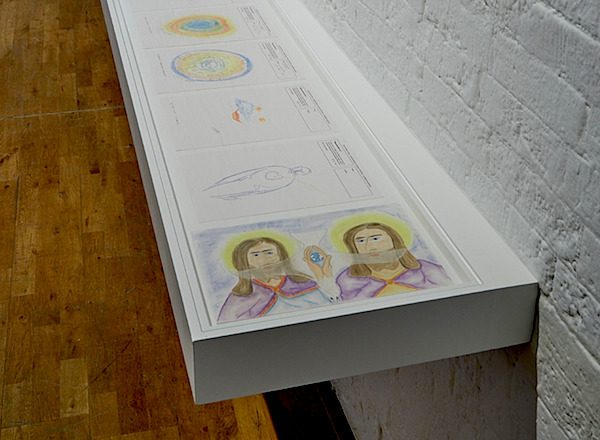

Words: Rev Jonathan Evens Photos: Courtesy Modern Art Oxford

Rose Finn-Kelcey: Life, Belief and Beyond, Modern Art Oxford, until 15 October 2017.

Footnotes: Priest for Partnership Development – St Martin-in-the-Fields (tel: 020 7766 1127, email: jonathan.evens@smitf.org) and St Stephen Walbrook (tel: 020 7626 9000, email: priest@ststephenwalbrook.net) Secretary – commission4mission (http://www.commission4mission.org/) Director – Sophia Hubs Limited (http://sophiahubs.com/) Twitter: @jevens / @commission4miss Blog: http://joninbetween.blogspot.co.uk/ Book: ‘The Secret Chord’ – http://www.thesecretchord.co.uk/ Meditations: ‘Mark of the Cross’ (http://www.theworshipcloud.com/view/store/mark-of-the-cross-pdf) / ‘The Passion’ (http://www.theworshipcloud.com/view/written/the-passion-the-passion)