Hodgkin Collection Sotheby’s London: Howard Hodgkin had an eye for the exceptional when it came to collecting. His personal taste resonates through his paintings, his ability to identify the extraordinary in unexpected places was deployed in his incessant hunt for art and objects of exquisite beauty. While each of Hodgkin’s paintings evokes his response to a very particular place, person or situation, the items he surrounded himself with in his home offer a personal portrait of their owner, one of the greatest artists of our time. The kaleidoscope of objects he so carefully drew together take us behind his paintings and cast new light on his aesthetic innovations, revealing what inspired him and what he held close. This October, Sotheby’s will exhibit some 400 items from the Howard Hodgkin collection is to be sold at auction in London on 24th October 2017.

Hodgkin remarked that he found painting solitary but that collecting bought him into contact with like-minded people

The objects with which he was surrounded reflected his passions, influences and interests and nourished his paintings. As items were purchased he would find a space for them, move them around and then finally settle on a place he felt they should stay, according to the other objects around them, creating dynamic visual dialogues. Objects from Italy to India, which suggest a modern day grand tour, were displayed side by side, heightened by the jewel-like tones with which the walls of his London home were painted. Spanning art history through time and geography, they offer a vivid revelation of his private world in all its intense and exhilarating glory.

Speaking of his creative method, his partner Antony Peattie explains, ‘most of his work took place in his mind’. His compositions and strokes were envisaged before he took up the paintbrush, enabling him to execute his vision with swift, confident brushstrokes. ‘”It’s all grist to the mill”, Howard insisted… He collected in order to create new work. What he acquired fed into his work.”

Howard did not keep his own work as he said they got in the way of new work, though he did keep two paintings from his debut show at the ICA in 1962, Bedroom and Travelling. “I have absolutely no desire to collect my own work, but do have what with age seems an almost unquenchable thirst for acquiring other things to look at,” Howard stated. “I think of collecting as a sort of virus really, and I was infected… It is an addiction”. So much so that he kept auction catalogues and a tape measure by his bed, marking things that he fell in love with.

Speaking of the forthcoming sale Antony Peattie said: “Howard liked the idea of a sale after his death. The objects have served their purpose to him, they were what he called his ‘Must Haves’ that, in some mysterious way, fed his work. But now they amplify his absence. After he died the house was so sad: all these objects remained in place but, after 33 years that we spent together, everything had changed. The sale represents a personal portrait of Howard. And it will enable his executors to fulfil his wishes.”

The discreet exterior of the house that was Howard Hodgkin’s London home in Bloomsbury for over 30 years gave no indication of the richness within. Opening the door was akin to stepping into one of his paintings. Art and objects of resounding beauty diffused to stunning effect resulted in unexpected dialogues.

With the surprising and inspired configurations in which he displayed objects, Hodgkin created an entirely new aesthetic. He had an unusually democratic approach to collecting, not adhering to the traditional collecting hierarchy of one medium taking precedence over another – an oil painting taking greater prominence than a watercolour, for example. So confident was he in his selection and of the importance of each piece to his needs that he created his own collecting alchemy. His approach was instinctive and his placements created unexpected yet harmonious arrangements, new works of art in effect.

Surprises lay around every corner of the house. A precious 17th-century Indian sandstone relief formed a backdrop in the kitchen to the artfully stacked china on display. Subtle and knowing conversations between disparate objects were formed across the spaces of rooms. An exquisite fragment from a carpet, with its interlocking geometric pattern, faced a series of wall-mounted Kashan star tiles, and the foliate motifs were echoed in monochrome form in the craftsmanship of an exquisite inlaid Mughal box.

Ornamentation is a prominent thread that runs through the great variety of objects he was drawn to, from both India and Islamic cultures. He especially sought fragments – particular motifs, calligraphy, colours and textures appearing in Ottoman, Indian and Islamic tiles, textiles and rugs. Fragments of calligraphy were not sought after for their meaning, but purely for the visual language of their linear forms, and he honed in on specific parts of larger pattern schemes. In doing so he focused on small yet powerful details, freeing his imagination from the original form.

He collected individual tiles from different periods and countries, spanning Kashan, Iznik and Mughal, and reflecting Hodgkin’s status as one of the greatest colourists of the last half century his concern with colour is evident in his choice of carpets. The intense colour seen in a fragment of the magnificent Von Hirsch carpet for instance, a masterpiece that had been split into four pieces, each of which was sought after by collectors around the world including Hodgkin; or the ‘Portuguese’ carpet fragment which illustrates both the very best of classical Persian dyeing skills and the mastery with which these colours were combined; the Lahore fragments showing just how well Mughal weavers could balance the acidic yellows, shocking pinks and blues of India to glorious effect, as well as including examples of quintessentially Mughal drawing of animals and birds. Textiles appear in the background to some of his prints, for example, Moonlight (1980), Bleeding (1981–2) and Mourning (1982).

Recurring motifs echoed around the rooms of his home, across a variety of objects of disparate cultural origins. He was fascinated by collage, inlaid items and surface patterns of all kinds: mosaics, Renaissance pietra dura, Cosmati, scagliola, cuerda seca, cloisonné and marquetry. It inspired him in 1992 when he designed the giant Banyan tree shadow mural for the British Council building in New Delhi, executed in black Cuddappah stone and white Makrana marble.

He was particularly drawn to sculptures as well as reliefs, in wood, in marble and in engravings, which created depth in a shallow space, just as his paintings did. He thought of his paintings as objects and painted over the three dimensionalities of the picture frame to incorporate it as part of the composition. He once commented that he liked to enter a room and find people present in the form of sculptures.

Further themes running through the works he collected include elephants and palm trees. Palm trees were perhaps both totemic and a signifier of the exotic, while elephants proved hard for him to resist. He wrote of elephants in 1983: “Perhaps the shifting volume and surface, the loose skin and the obvious structure inside it, the colossal weight which can defy gravity with a leap in the air then sink to the ground in a heap like a mountain, were to the Indian artist what the changing forms and moods of the human body are supposed to have been to the Post-Renaissance European artist.”1 His artist heroes also played their part in his collecting. He loved prints, mezzotints and engravings and was delighted to find that in these media he could own work by Breughel, Hogarth, Piranesi and William Blake.

Even items that might seem anomalous are intimately linked to the other objects in his home, as well as to his own paintings, such as a selection of flags. They fascinated him for their symbolism, their stripes and colours that carry the weight of a whole country, and they appear in his paintings In a French Restaurant (1977–9) and Flag (2006–2010), and in the print Put Out More Flags (1992).

Hodgkin collected in such depth that despite covering almost every surface of his home many of his acquisitions were not displayed. The basement library held a rich trove of prints, paintings, fabric, books and furniture and exquisite fragments – a palette of colours and a reference library for the treasures that he had sought out. Items consigned there were not relics, but an astounding array of source material of the most varied and wonderful kind. Many items were acquired on his travels, but never as mementos. “I particularly don’t like objects of sentiment: people who have things not because they like and admire them but because they have associations. You should have what you want, what you like, around you.” 2 His criteria for acquiring: “Things have to be acquired out of necessity, as well as passion.”

Friendship was important to Hodgkin. As his recent exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery exhibition so eloquently demonstrated, his relationships with people – fellow artists, writers, collectors, academics, family and friends – have been at the centre of his life but also inform his best work. The two early paintings in the sale are critical to understanding both subject and style. Painted in 1960–61, Bedroom recalls a moment in a hotel room in Paris together with his wife Julia, and their friend Mrs Burt. Travelling, painted at the same time, reflects a lifelong interest in experiencing other places.

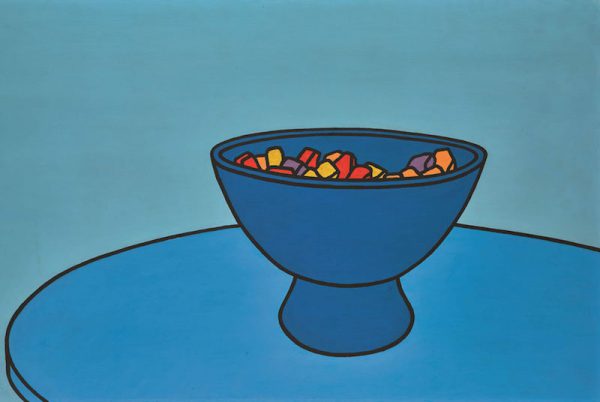

His friendships are powerfully represented in his personal collection by the works of fellow artists with whom he was particularly close and, crucially, those whose art he respected and admired. He once described Patrick Caulfield as “the closest I ever came to having a painter-colleague”, and it is significant that one of Caulfield’s most important still life paintings should end up in his collection. Painted in 1966, Sweet Bowl reveals Caulfield’s heightened awareness of both colour and space, an interest that he clearly shared with Hodgkin. The dynamic minimalist style Caulfield developed where the hand of the artist is almost invisible is, however, almost the extreme opposite of Hodgkin’s own energetic application of paint and it is interesting to consider their work side by side. Further friendships represented by works that Howard owned include Robyn Denny, Peter Blake and Stephen Buckley.

The presence of two works by Bhupen Khakhar in the collection is also the result of a long and storied friendship between the two artists. De-Luxe Tailors, 1972 (est. £250,000–350,000) which featured prominently in the recent Tate retrospective of Khakhar’s work, epitomises the artist’s early style and is a signature work from this period. Hodgkin was in many ways his mentor and in some ways his liberator. Hosting Khakhar in England at various times in the late 1970s, finding him teaching positions and advocating for his works with galleries and museums, Hodgkin helped Khakhar to expand his horizons: his art seemed to become freer, looser, funnier and unflinchingly honest. It was Howard Hodgkin’s friendship and encouragement that may have sparked Khakhar’s recognition as one of India’s greatest 20th-century artists.

Hodgkin remarked that he found painting solitary but that collecting bought him into contact with like-minded people. Furthermore, the discriminating eye that he developed was nurtured by close friendships with experts in the field. It was Hodgkin’s art master at Eton, Wilfrid Blunt, who first introduced him to nonWestern art and who inspired him to collect his first examples of Indian painting. Later, Hodgkin became friends with the collector Robert Erskine and through him the network of various Parisian dealers, including Charles ‘Uncle Charlie’ Ratton. Robert Skelton, then Assistant Keeper at the V&A, became a lifelong friend with whom the artist first visited India in 1964. It was with Skelton that Hodgkin was able to meet other connoisseurs and collectors, including Jagdish Mittal, Kumar Sangram Singh, Milo C. Beach and Stuart Cary Welch, whose own celebrated collection of arts of the Islamic and Indian world was sold at Sotheby’s in 2011.

Hodgkin first encountered the word antique in a comic, at the age of seven, when he had been evacuated to America during World War II – Minnie Mouse was on the phone talking about the footstool she had just bought and he assumed the word was pronounced Anti-queue. By the time he had his first retrospective, at the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford in 1976, he was better known in the art world as a collector than as a painter. In the 1970s trading in antiques supplemented his income as an artist and art teacher, and he specialised in frames – hitchhiking from Bath to London in his pursuit as he never learned to drive. His quest for particular frames continued throughout his life and they came to play a significant role in his paintings. When he travelled he often sought out frames to take home with him, incorporating them in his paintings of the place or trip from which they originated.

So honed was his eye that he particularly delighted in finding overlooked treasures. “There was delight in the orphan: finding some misrecognized piece, restoring it to its rightful primary place,” his partner comments. “He once bought an early 19th-century mahogany teapot, which stood on four tiny lion’s paw feet. Holes had been drilled through the faces above them. Nobody knew what they were. Howard had them photographed and the images enlarged. They are now identified as late Roman Ivory casket fittings. He gave them to the British Museum, in memory of his father, Eliot Hodgkin.”

Howard Hodgkin came from a long line of collectors and grew up surrounded by the eclectic acquisitions and assemblages of his great-grandparents, John Eliot Hodgkin, and his wife Edith, whose inventory of art was published in 1900 in three volumes as Rariora, listing ‘things wondrous rare and strange’. He evidently shared their passion for tiles – they collected English tiles, whereas Howard was drawn to tiles from Persia, India, Turkey and Damascus from the 12th century onwards.

It was partly with the help of his cousin, Margery Fry, that when Hodgkin left school in 1949 he won a place at Camberwell Art School, and then moved on to the Bath Academy of Art, Corsham. At Camberwell, he was taught by leading Euston Road School painters Victor Pasmore and William Coldstream, and remembers considerable peer pressure to conform to a house style. “I was already an outsider even then,” he recalls, and by the time he went to Corsham, he already had his own artistic language. He studied at the Camberwell School of Art in London and the Bath Academy of Art in Corsham from 1949–1954. Critical recognition for his work grew steadily through the 1960s and 1970s, and by 1984 he was asked to represent Britain at the Venice Biennale, swiftly followed by being awarded the Turner Prize in 1984. Since then Hodgkin has been the subject of numerous major international exhibitions, including the Hayward Gallery, London (1996), ‘Howard Hodgkin: Time and Place 2001–2010’, Oxford, Tilburg, California, (2010–11), ‘Howard Hodgkin: Absent Friends’, The National Portrait Gallery, London (2017), ‘Howard Hodgkin: In The Pink’ at Gagosian, Hong Kong (2017), and the current show ‘Howard Hodgkin: Painting India’ at the Hepworth Wakefield in Yorkshire, England, which closes on 8 October 2017. ‘Howard Hodgkin: India on Paper’ will open at the Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, on 14 October 2017 and will run until 7 January 2018.

Hodgkin Collection: Visit Sale Here