Three very different books that somehow reflect different facets of the same situation. The most obvious relevant – the title tells the tale – is Georgina Adam’s The Dark Side of the Boom, subtitled The Excesses of the Art Market in the 21st Century (Lund Humphries). This certainly offers plenty of thought-provoking material. ‘Who owns the rights to a work of art?’ it enquires. And, even more to the point: ‘Who authenticates?’

Those who run our museums are horrified by what they see going on in the great auction rooms – ELS

As a relatively naïve British reader, but also as a sometimes bemused observer of British art institutions, I was struck by several things in Adam’s lucid text. First, that while British experts certainly play a role in complex games of authentication, the British art world plays only a comparatively minor role in the crazy games now taking place, where a top layer of prices increasingly separates itself from what is happening in the rest of the market. It’s often much easier to sell a $7m artwork than one that is notionally worth only $70,000. That is, if you have access to the right hype.

Telling little is said about major British institutions. One factor is that they don’t usually have the funds to buy at the very top of the market, even in cases when they are able to put together deals where government money is topped up by private donations. Another is the ‘goody-two-shoes’ factor – those who run our museums are horrified by what they see going on in the great auction rooms and the great art fairs. Their reaction, increasingly, has been to run away into self-righteous populism. They love things like performance art, video, temporary installations. They are, however, reluctant prisoners of the fact that their public is still responsive to great historical names. And in the kind of society we have now quite a few exhibition goers seem prompted to go to exhibitions not only to look at the art but to look at the money. ‘Hey, here’s a Leonardo painting – what did yesterday’s paper tell us it’s worth?’

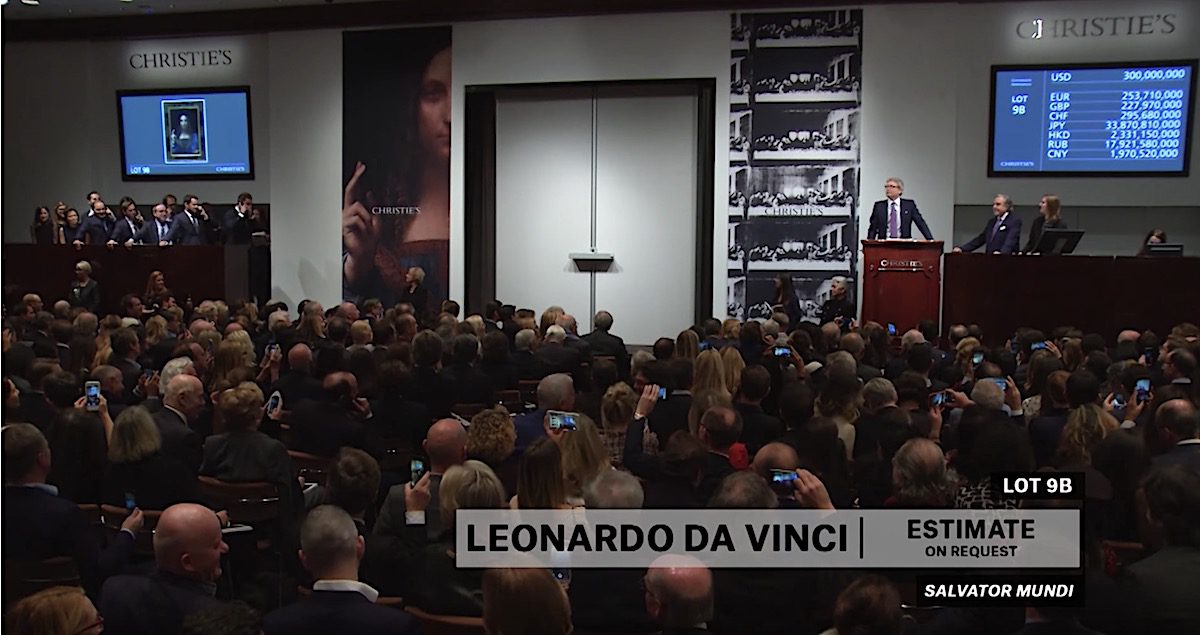

A telling case in point is the recently rediscovered Leonardo Salvator Mundi, which made its first real public appearance in the National Gallery’s Leonardo at the Court of Milan (November 2011-February 2012). Intimately connected with this rediscovery was the British expert Martin Kemp, who has now published Living with Leonardo: Fifty Years of Sanity and Insanity in the Art World and Beyond (Thames and Hudson).

This text, admirably modest in tone, is in fact largely concerned with not one, but two, recent Leonardo ‘discoveries’. One is the Salvator Mundi; the other is the profile portrait of a girl entitled La Bella Principessa. The Salvator is now firmly in the record; La Principessa is still scrabbling to be let in. Kemp, who believes in both attributions, explains why this is the case.

However, there is more to it than this. The Salvator is a much reconstructed work, which emerged into public view only after many years of restoration When it was recently sold by Christie’s for the record price of $450 million (the buyer being, perhaps through intermediaries, the Louvre Abu Dhabi), this prompted a re-examination by a site called artwatch.org.uk, well known for interventions in difficult matters of this kind. What this intervention seemed to prove, with striking visual evidence, was that the painting had been touched up yet again after it was exhibited in London. Christ’s cheeks, for example, now have a manly blush they didn’t previously possess.

The painting, as a physical object presented to your gaze, more than half a millennium after Leonardo touched it, requires the eye of faith. It’s the eye of faith that tells you, not only that Leonardo was the author of this work, but that, in its present state, it represents – more or less – what he may have intended. And what strengthens your confidence that this is so is in fact – yes, of course – the price. In our society, nothing validates like money.

Another new book from Thames & Hudson, The Lives of the Surrealists, raises some related questions. Morris claims to be ‘the last surviving Surrealist artist’, though he is in fact much better known for other activities – for his 1967 book The Naked Ape and for the Zoo Time and other television programmes. His new book offers brief biographies of 32 Surrealist artists, of varying degrees of eminence, some of them (de Chirico, Henry Moore) rather tangentially connected to the main Surrealist Movement, others (Giacometti) connected to it only for a while. Thanks to its self-appointed Pope, André Breton, the main Movement had rather a taste for excommunications.

The Lives are crisp and clear. This is a very useful book. It has one feature that is both amusing and informative. Each biography is headed, amongst other pieces of information, by a list of the ‘partners’ of the artist concerned. In the case of those of the male gender, the sum total is a formidably large number. Male Surrealists, to put it bluntly, were a band of Minotaurs – devourers of women.

It is, of course, true that there were female Surrealists who counted for something, though not many: Leonora Carrington, Leonor Fini, Meret Oppenheim, Dorothea Tanning. About the only other place in the history of early Modernism where you find important women artists is among the members of the Russian avant-garde.

When Surrealism flourished, the #MeToo movement was still a long way in the future.

The Dark Side of the Boom, The Excesses of the Art Market in the 21st Century, Georgina Adam (Lund Humphries)

Living with Leonardo: Fifty Years of Sanity and Insanity in the Art World and Beyond, Martin Kemp (Thames and Hudson)

The Lives of the Surrealists Desmond Morris (Thames & Hudson)