In the society we now have, photography has become the dominant medium for conveying news, opinion, social criticisms of all kinds. Painting has largely, though not entirely, withdrawn from tasks of this sort, and is often content to create a separate universe of its own, where aesthetic judgments and sensations are the only things that count. This comes up in a big way in a photography show entitled Another Kind of Life, which is currently at the Barbican Art Gallery. It features the work of twenty photographers, some very well known, and the catalogue includes a chunk of what it calls Archive Material.

The headings given to three of these ‘archive’ sections give a clear view of what the exhibition is about:

1. Tranvestia, 1961-1967 (material from an underground periodical about transvestites.

2. Brooklyn Minority Report: An Inside View of the Aspirations of Embattled Youth (1960)

3. Streets of the Lost: Runaway Kids Eke Out A Mean Life in Seattle (1983)

The only way in which this is slightly misleading is that it suggests that the contents of the show are entirely American. This is not the case. One section features the work of Dado Moriyama, a Japanese photographer who offers a disorienting vision of Japanese society in the 1960s. There is another Japanese, Seiji Kurata, who recorded Tokyo low-life a decade later. Paz Errazuriz portrays a group of Chilean trans-people, living under the oppressive regime of Augusto Pinochet. The Ukrainian Boris Mikhailov, in a famous series called Case History, recorded the collapse of civil society in his native Kharkov, as Soviet power crumbled into dust and an alternative struggled to be born. Dayanita Singh, originally commissioned by the Times of London, recorded the lives of the eunuch community in New Delhi. In 1989, the time when she arrived back in her native country, after studies in the USA, it was estimated that there were about 1 million eunuchs living in India.

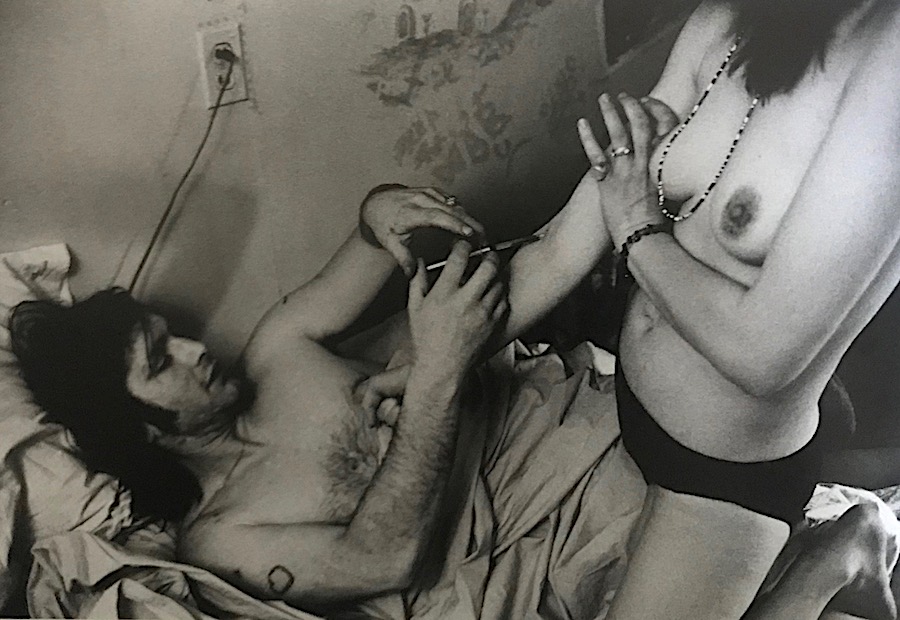

As this brief listing suggests, the show stresses both economic deprivation and deviance from sexual norms. Not all of the minority groups depicted are ones that attract pity, or at degree of social approval. Danny Lyon, in the 1960s, recorded the American biker community with an evident sense of self-identification. Larry Clark, at about the same time, produced his iconic Tulsa series portraying dropouts and druggies.

One senses that both Clark, and most of the other photographers featured, came to identify strongly with the minority communities they portrayed. These are not distancing, objectifying images, and this endows them with a large part of their impact.

Several questions arise. Though the pictures identify with social outsiders, transvestites and eunuchs among them, it has remarkably little to say about women. There are few pictures here where women are front and centre. When they seem to be so, they often turn out to be images of men in drag. Few of the photographers are women, though there are some famous members of the gender among them – Diane Arbus and Mary Ellen Mark. In this sense the show, though it includes images from the current decade, begins to seem like a memorial to things that are passing, if not as yet fully past.

It’s also true that while there are many strong individual images, the real effect is usually cumulative – it is the sequences of pictures, all from the same photographer, expressing his or her point of view, that makes the fullest effect.

There is nothing here that makes you (or shall I say me?) stop and stare, and take it away, once the staring is done. Yours forever, incorporated into your own individual psyche.

The words that echoed in my head as I left the show were those of a famous Bob Dylan song:

Yes, and how many times can you turn your head

And pretend that he just does not see?

The answer is blow’n ‘in the wind.

Words: Edward Lucie-Smith Photos: P C Robinson © Artlyst 2018