What is a mastaba? Some dictionaries will tell you that the word means a bench, but more usually it’s a term used to describe an early Ancient Egyptian form of grave monument. A type that was in use even before they began to build the pyramids.

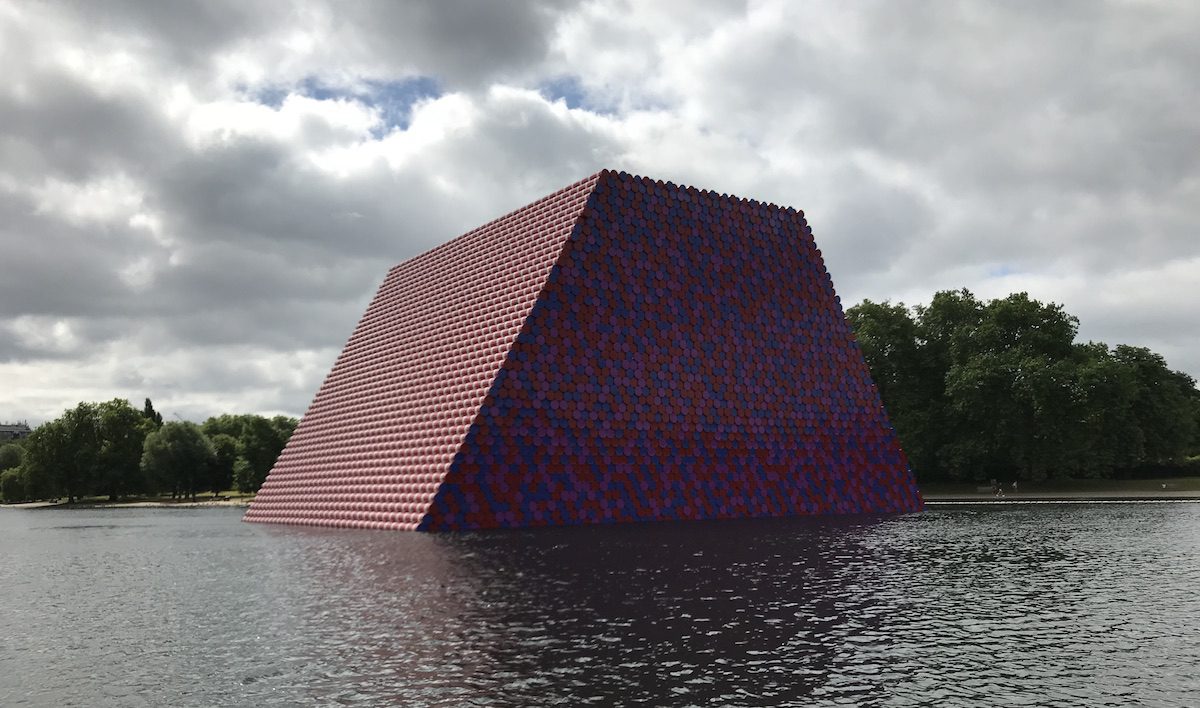

So, what’s a huge grave monument made of oil barrels doing floating in the Serpentine, Hyde Park’s much loved recreational lake?

It’s there because it’s the work of Christo, the famous Bulgarian-American sculptor, photographer and conceptual artist. Mastabas made of oil barrels aren’t the only things by any means that he’s made in his long career, usually in collaboration with his late wife Jeanne-Claude. You’ll find quite a big documentation of these and other projects, together with a few more oil barrels in less ambitious configurations, at the Serpentine Gallery, close to the lake. There are models, blueprints and diagrams galore. These extras, of course, will continue to exist when the improbable floating monument on the lake has long since disappeared, as similar Christo projects have first manifested themselves then vanished during the artist’s lifetime of celebrity. This one will be gone by the end of September, so hurry over to the park and take a look while you still have the chance. Christo doesn’t build for the future, as those distant Egyptians did in their day.

One of the lessons this project seems intended to inculcate is that not all monuments are built for eternity. This mastaba is addressed to the here and now. Once it’s gone, it’s gone. All that’s left is the vibe that you, the spectator, carry away with you. You look, and you incorporate it into yourself – it becomes part of your psyche, and its fragility, despite its looming insistence on being looked at in these unexpected surroundings, is very much part of its appeal.

As it happens, it’s not the only thing of its sort that happens to be visible in London right now. Make your way to Trafalgar Square, and there you will find a full-scale Assyrian bull, modelled on one that until recently stood guard over the ruins of the ancient city of Nineveh, and which was recently destroyed by Isis. The work of the American artist Michael Rakowitz, it is made of the cans used, not for oil but for date syrup. The artist’s title for this is The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist.

I think there are slightly self-contradictory conclusions to be drawn from the public presence of these works by two different artists, on extremely visible and central sites here on our great metropolis. One, obviously, is that not all artworks have to aim for an extended lifespan. The syrup-can winged bull may survive a bit longer, though necessarily in a different location from the one it has now, from Christou’s ephemeral oil-can mastaba. Having made its point, the bull will be jostled off the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square by some other project.

The other is the enormous resonance that things done and made in the past can have over our minds in the present. Both artworks stress the continuing influence of past events, even very remote, half-forgotten ones. They also serve as warnings and exemplars. In these two cases, it is not just the warning is embodied not just in the forms they take, but what we know these sculptures are made of common-or-garden tin cans, emblems of our grimy industrial present.

I’ve sometimes complained here about the increasing, and increasingly self-satisfied moralism of the British contemporary art world, especially the part of it that is firmly in the grip of official bodies. Let me say it now: sometimes, at least, this does have a point.