The artist Duncan Grant (1885-1978) was a charismatic, much-loved central figure in the Bloomsbury Group, a collection of friends, including the writer Virginia Woolf, the critic Clive Bell, the painter Vanessa Bell – Virginia’s sister – and the deeply influential economist and writer Maynard Keynes that has fascinated scholars and readers for decades. Their intertwined relationships and sexualities, not to mention intellectual and artistic achievements, have proved of lasting fascination from the latter half of the 20th century and on into the present, with an ever-growing audience nourished by academic studies, major biographies, popular books and exhibitions.

What is true in 2021 is how graceful and charming the whole appears – MV

Some of this may be attributed to the inviting notions of profound friendships that endured through understandable tensions and shifting allegiances, and much to the undeniable importance of their cultural influence in the anglophone world and beyond. The fact that American scholars have been just as absorbed in Bloomsbury history has also helped. In the very insecure and frightening times that we are living through, the attraction of friendship, mutual support and understanding, has perhaps never been higher.

There is a very solid testament to the allure and interest of the group in Charleston, the relatively modest 17th century stone farmhouse in Sussex, which has been continually modified and decorated: it was ‘georgianised’ in the 18th century. But its credentials have been burnished, and its importance assured, by the captivating renovations and decorations when it became the beloved country house of Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. Vanessa Bell evidently had a beautiful speaking voice, and it was she who was the relatively calm centre of the group, credited with somehow keeping it together, tight at times, loose at others. Charleston’s guidebook, sub-titled A Bloomsbury House and Garden, subtly and seductively indicates that the house itself is a Bloomsbury muse.

This exhibition, its opening prolonged for a year by the pandemic, commemorates 101 years on the 100th anniversary of Grant’s first solo exhibition (1920) at the Carfax Paterson gallery in Old Bond Street; Grant showed just over thirty paintings, and the collection engendered mixed reviews. The Times said he had a great talent but could be wilful, and the paintings could exhibit a kind of automatism; the Telegraph acknowledged “certain elements of attractiveness” but said some was “wilfully grotesque and absurd”, and altogether was of the “most defiant modernity”. These critics, however, did take Grant seriously, and little did they, writing in the 1920s, imagine what was to come in the visual arts.

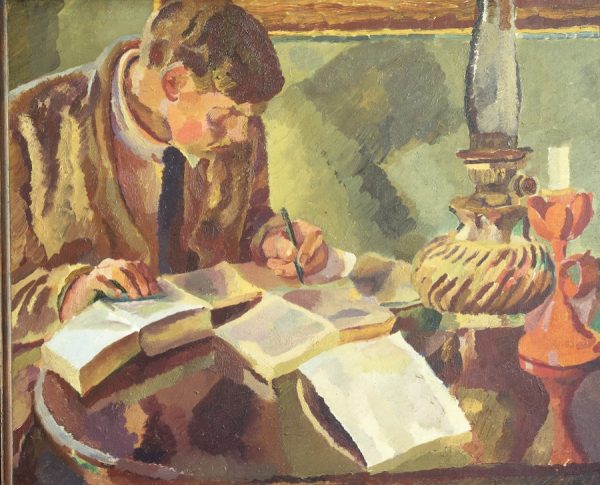

What is, of course, true in 2021 is how graceful and charming the whole appears. A poignant, even wistful Room with a View (1919) looks out into the garden at Charleston; Vanessa Bell is reclining in her deck chair just outside. The Student unpretentiously shows David Garnett in his mid-twenties, and dressed conservatively in a jacket and tie, sitting at a table with several open notebooks, and with immense concentration writing away with from an open book to the side. Neither study gives a hint of being posed, rather that they are taken from the pulse of daily life, observed by the artist. There is a plethora of still life: table-top, the perhaps inevitable platter of fruit, a coffee pot, a washstand, vases and bowls, a plaster cast, a bookcase, a jug of flowers, some decorative studies. We look out too, to the garden and the neighbouring barns, the surrounding farm buildings, the cowshed. One painting The Interior shows us Grant’s two lovers at the time, David Garnett and Vanessa Bell, being observed by Grant himself: Vanessa is painting, and David Garnett is working at the table on a difficult translation from the Russian. A portrait of Vanessa, in the red dress in which she was painted several times – once when pregnant, and thought to be one of the first times a secular domestic pregnancy was shown, rather than that of the Virgin- is vivid, even compelling.

There is a superb complementary exhibition at Philip Mould Gallery, 18-19 Pall Mall, St James’s London SW 1 (until 10 November), accompanied by an outstanding and detailed publication, titled Charleston The Bloomsbury Muse (£27.50), with essays by diverse experts. We are reminded that Charleston was only saved as a house to be visited by the public in 1979, and yet now it is wound tightly into the cultural life of England – and well beyond.

This reviewer was lucky enough to meet Duncan Grant once or twice in his old age (as well as David Garnett) and can testify to his unforced charm: he was a delight. It was a memorable experience: he was curious, outgoing, and in that cliché which does really embody a truth (I always think that is why some phrases become clichés) was so full of life. It is this sense of a life well lived that somehow pulses through these unassuming pictures, and pictures they are with daily life their inspiration.

What the exhibitions reveal is perhaps a truism but potent for all that: there is always more to see and learn. The friendships, sexual and platonic, and often both, not to mention the creative and intellectual achievements of Bloomsbury, still have so much more to show us, literally, figuratively and metaphorically. Enjoy.

Words: Marina Vaizey ©Artlyst 2021 Photos courtesy of Charleston

Duncan Grant: 1920, Charleston, Firle, Lewes, East Sussex, BN8 6LL – 18 September 2021-13 March 2022

Visit Here

Charleston: The Bloomsbury Muse, Philip Mould 14 September – 10 November 2021

Visit Here