There is a conundrum at the heart of the work of Emil Nolde. How could it be that this superb experimental colourist, this embracer of all things which seemed ‘modern’ at the time – an interest in ‘primitive’ societies that provided a sort of prelapsarian alternative to western culture, a fascination with the freedom of dance and the power of the erotic, the daring to paint pictures that expressed not how the world looked but how it felt – could also be a committed member of the Nazi party. And does it matter?

Nolde would, eventually, be denounced as a degenerated artist, despite his life-long commitment to National Socialism

When the celebrated writer George Steiner was asked that thorny question about how could it be that the Nazis listened to Bach and Beethoven in the evenings having spent the day putting people in gas ovens, he responded “[there are those who are] certain that the cultivation of the sensibility of beauty, of humanity, of seriousness in art, in literature, in music and painting, would be some kind of help, some kind of barrier, against inhumanity. But it’s all over our world: inhumanity can be combined with high aesthetic experience.” The interviewer then asked: “So the humanities don’t necessarily humanize, civilization doesn’t necessarily civilize —”. No, Steiner answered: “It may indeed barbarize.”

Nolde grew up in a house where the only book was the Bible, which he read avidly. North German Protestantism, at the time, was pious, fundamentalist, conservative and deeply rooted in the idea of being close to the soil and land. In 1906 he painted Free Spirit. In flat planes of vibrant pink, green and orange he placed his biblical figures against an urgent blue background, depicting Christ as an outsider and prophet. His work was imbued with a religious pathos and deep spiritual yearning, comparable to Wassily Kandinsky’s near-abstract compositions that symbolised the mystical re-birth of Mother Russia. Like the most celebrated ‘moderns’ Nolde was not afraid of making pictures that were not initially pleasing to the eye. In fact, he claimed that the best art was often difficult on initial viewing and that every significant artist created new values and new forms of beauty. Not lacking confidence, he viewed himself as ahead of his time, a prophet for a new artistic religion, drawn to the chthonic and elemental.

The exhibition in Dublin opens with the extraordinary painting of 1918, Brother and Sister. The almond-shaped coal-black eyes, the red gashes for mouths, the skin yellowed as if by lamp light and the closeness of the two figures’ heads suggest an incipient, possibly incestuous, relationship, completely at odds with the piety of the farming folk from the border area between Germany and Denmark that Nolde called home. There is nothing provincial about this painting. It has something of the harsh loucheness of Max Beckmann or Otto Dix. The intense crepuscular light is reminiscent of Van Gogh’s Potato Eaters, while the vibrant colours echo those of the Fauvists and the young artists of the Brüke group, to which Nolde briefly belonged. While Ecstasy, painted in 1929, shows a naked woman, kneeling, her legs spread wide, her bright blue eyes bulging, her scarlet nipples pert with orgasmic bliss as she leans back beside a woman with flaming red hair who is brandishing a blue cross. Is this Mary Magdalene or Mary, the mother of God? A profane version of the Annunciation or simply an excuse to paint the wanton or lascivious? Whatever Nolde’s psyche at the time, it is an extraordinary painting. The sacred and profane are the binaries here to which he returns to again and again. Uninhibited ecstasy is also suggested in his dance paintings. Ritualistic, wild and uninhibited, they are more bacchanalian and Rite of Spring than Mazurka. The fiery expressionistic colour, the frenzied movement place him firmly in the camp of the avant-garde. So, it is hardly surprising, that with Hitler’s jealous hatred of ‘modern’ art, Nolde would, eventually, be denounced as a degenerate artist, despite his life-long commitment and unrepentant support for National Socialism.

Emil Nolde (1867-1956) ‘Paradise Lost’, 1921

And yet? And yet? Are there clues to his more unpalatable views within the paintings? I suggest that there are. Take the 1908 painting of Market People, a group of hatted, bearded men clustered together, no doubt doing business. Many his local agrarian north German neighbours. But on the right, there’s a figure in green with a small cigar. He seems to be leaning on some sort of counter. With his hooked Semitic nose could he be a Jewish money lender? Again, his 1911 painting of Slovenians shows a couple, the man with a black beard, the woman dishevelled in a blue hat, wide-eyed, it’s implied with drink, indicated by two tall glasses and a bottle in front of them. It is a terrific painting. The movement and fluidity suggesting their slightly inebriated state. But Nolde has not painted them as individuals but as types. Foreigners. Strangers. Swarthy ‘others’. Compare this to his extraordinary self-portrait, executed in cool pale tones, in which his icy blue eyes dominate that is a rendering of pure Arian genes.

It is this problematic relationship between modernity and a longing for an uncorrupted, unchanging Heimat or homeland that was to take him on his voyage to the South Seas of the Pacific in October 1913 in search of a pristine world, which he then complained he could not find. Standing in front of his Manus Men 1914, inhabitants of Northern Papua New Guinea, I could not help but feel uncomfortable. With their fuzzy hair, their earrings and necklaces and a one of them with a bone through the nose, they seem emblematic of the ‘Noble Savage’. Again, types not individuals. There is none of the tenderness, say, of Gauguin, towards his Tahitians.

Yet, ironically, on the 23rd August 1941, Nolde received a letter from the President of the Reich Chamber of Visual Arts informing him that his paintings ‘did not meet the standards expected since 1933 of the art produced by all visual artists working in Germany’. Two months later he was forbidden to sell, exhibit or publish his art. It was then that he painted his ‘unpainted pictures’, watercolours of drenched virtuosity that mined myth and fairy tales with a cast of grotesque fantasy figures. Slowly a myth grew up, encouraged by Nolde himself, that these luminous little paintings were the result of not being allowed to paint in oil. Shrouded in a veil of secrecy, he suggested that his ‘unpainted pictures’ grew from the painting ban. But the truth may be more complex. That he simply felt that they revealed too much about him, laid bare his soul.

Nolde continues to pose problems for a modern audience. The brilliant jewel-like flower paintings, the brooding, gorgeous sea and landscapes reveal an imaginative virtuosity. It is easy to apologise for him because of the luminosity, the saturated colours of these stunning paintings, seeing him simply as a painter who wanted to express his love and attachment for his beloved homeland. But there was, in this Eden, a secret heart of darkness.

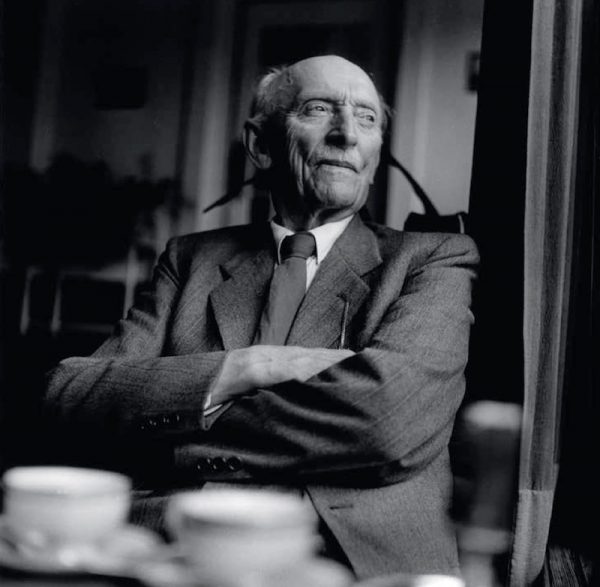

Top Photo: Emil Nolde Detail, Large Poppies Red 1942

EMIL NOLDE ‘Colour is Life’ National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin until 10th June 2018

The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh 14th July – 21st Oct 2018

Sue Hubbard’s new novel, Rainsongs is published by Duckworth. Purchase Here