There’s no doubt that the Jean Dubuffet show just opened at Pace here in London would be entirely worthy of a great museum – that is, if it happened to be presented in one of our official institutions, rather than in a space belonging to a leading international commercial gallery.

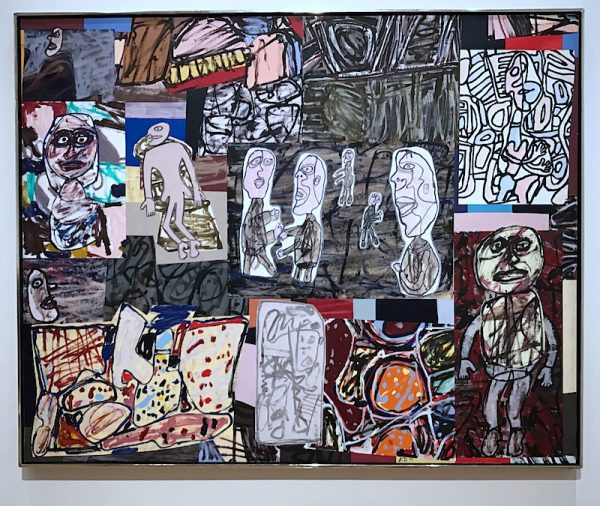

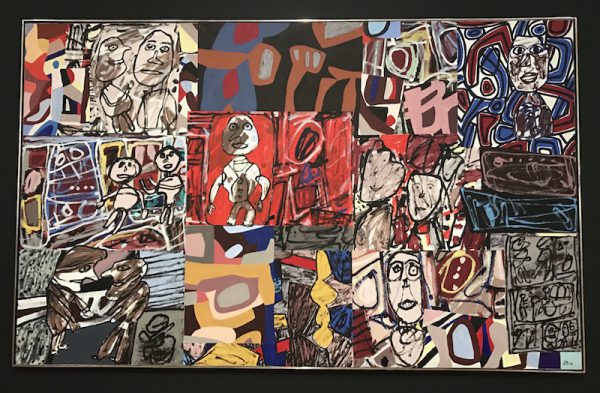

The works in this series are large collages, produced between 1975 and 1978

Entitled Les Théâtres de Mémoire, it belongs to a relatively late phase of Dubuffet’s career. The works in this series are large collages, produced between 1975 and 1978. As the catalogue for the current show explains:

‘These collages, or “picture assemblages” as Dubuffet occasionally referred to them, are made from disparate elements cut from his paintings on paper…which the artist then rearranged and glued on to large-scale canvases.’

The elements used thriftily recapitulate images from a number of previous series, among them those from L’Hourloupe, (1962-74), the series for which the artist is now perhaps best known.

By the time the works to the Théâtres de Mémoire series were made, Dubuffet, after a somewhat stuttering start, was extremely well established internationally. He did not devote himself fully to making art until 1942, by which time he was already in his forties. He first exhibited outside of his native France in 1947. The show was in New York, at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, which had a mission to support the idea that Paris was still the centre of innovation in art, despite the hiatus caused by the war years.

This was also the epoch at which Dubuffet began to devote himself to the idea of Art Brut – a concept that spanned the work of both trained artists, such as himself, but that of naïve, or ‘outsider’ artists, with no professional formation, practitioners with whom, in contrarian fashion, he wished to associate himself.

After the war, Dubuffet rapidly became a key personality in the Parisian art scene. By the 1960s, he was also enormously successful internationally, with a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1962, which travelled to the Art Institute of Chicago and the Los Angeles County Museum. Other exhibitions in major official spaces followed: Palazzo Grassi, Venice, in 1964; then in 1966 shows in Dallas, Minneapolis, the Tate Gallery, the Stedelijk in Amsterdam, and the Guggenheim in New York, followed by another show at MoMA in 1968, plus one at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. These certified not only Dubuffet’s personal reputation but that of the culture from which he came.

It is not too much to say that Dubuffet was thought, in the 1960s, as the saviour of the continuing Modernist tradition in Paris – the artist who demonstrated that the creative leadership, for Europe at least, was still firmly rooted there.

This wasn’t a situation that would last. Now, just short of 50 years later, art in France seems curiously isolated. Contemporary French painting, in particular, no longer competes reputation-wise with what is happening in Germany, in Italy, or even here in Britain.

There are people, I know, who see Dubuffet as still being influential today. They cite, for example, resemblances between his work and that of Jean-Michel Basquiat, the New York graffiti artist who is now fetching enormous prices at auction. Basquiat may indeed by a big financial deal right now, attracting, for some reason, rich Japanese collectors. The fact is, however, that he died in 1988, almost thirty years ago, and there has been nothing much like him since. Today’s fashionable graffitists resemble Banksy far more than they do Basquiat.

Confronted with the show at Pace, which is an excellent one in its own terms, showing Dubuffet at more or less the top of his game, with huge, intricate compositions, what strikes me is that it is so clearly the end of something, not the beginning of something.

The impulse towards the primitive, so important in the history of the Modern Movement which ran its course from the early 1900s until somewhere in the late 1970s, when art began to be Post Modern, is displayed here at its last gasp. During the decade when these collages were made, it began to be replaced by other things, such as the much-discussed impulse towards ‘appropriation’.

Modernist Primitivism came in two forms – admiration for the art of tribal Africa, and also a fascination with the art of children, and of untutored artists in general, unsullied by any kind of academic impulse that might sully its essential purity and sincerity. Art Brut, as Jean Dubuffet christened the second of these two impulses, was not only ‘art in the raw’, but art naked, without pretensions. Picasso felt this impulse long before Dubuffet, and it appears intermittently in his work from Cubism onwards, but particularly strongly in what he produced towards the end of his life. Dubuffet tried to systematise it, and, in doing so, it seems to me, he pretty much killed it off. These big collages are too elaborate and sophisticated for their own good. What they gain in complexity they lose in sincerity. And that’s a big loss.

Jean Dubuffet – ‘Theatres of memory’ Pace London Until 21 October FREE Visit Here

Gallery Notes: Theatres of memory is the first exhibition dedicated to Dubuffet’s Théâtres de mémoire series in over three decades. Organized by Arne Glimcher, the founder of Pace Gallery, the exhibition features eight monumental paintings on loan from significant European museums and foundations including Fondation Dubuffet, some of which will be displayed publicly for the first time.

Jean Dubuffet (b. 1901, Le Havre, France; d. 1985, Paris) began painting at the age of seventeen and studied briefly at the Académie Julian, Paris. After seven years, he abandoned painting and became a wine merchant. During the thirties, he painted again for a short time, but it was not until 1942 that he began the work which has distinguished him as an outstanding innovator in post-war European painting. Dubuffet’s interest in art brut, the art of the insane, and that of the untrained person, whether a caveman or the originator of contemporary graffiti, led him to emulate this directly expressive and untutored style in his own work. His paintings from the early forties in brightly coloured oils were soon followed by works in which he employed such unorthodox materials as cement, plaster, tar, and asphalt-scraped, carved and cut and drawn upon with a rudimentary, spontaneous line.