I’ve just been reading a remarkable book, published last year, that seems to have received almost no attention here in Britain, save for a brief anonymous review in The Guardian. There also nothing much about it that I can discover, published in the United States.

Called, ‘Confessions of an Old Jewish Painter’, it is an autobiography written by the late R.B. Kitaj, an American artist who once enjoyed a very prominent place in the British art scene, and also to a considerable extent internationally. It has been published, in English, by the German publisher Schirmer/Mosel, which has somewhat of a speciality in publishing books about leading American artists. The source is a somewhat disorderly manuscript left behind by Kitaj after his death, edited by the German scholar Eckhardt J. Gillen. There is a preface by Kitaj’s friend David Hockney and over 200 illustrations, among them 33 photographs by Lee Friedlander of Kitaj and friends. There are Biographical Notes, written by Gillen, plus notes on people who were important in Kitaj’s life and also a serviceable bibliography. Maddeningly, the one thing the book lacks is an index. With such a complex personality and life-story, this is a big lack.

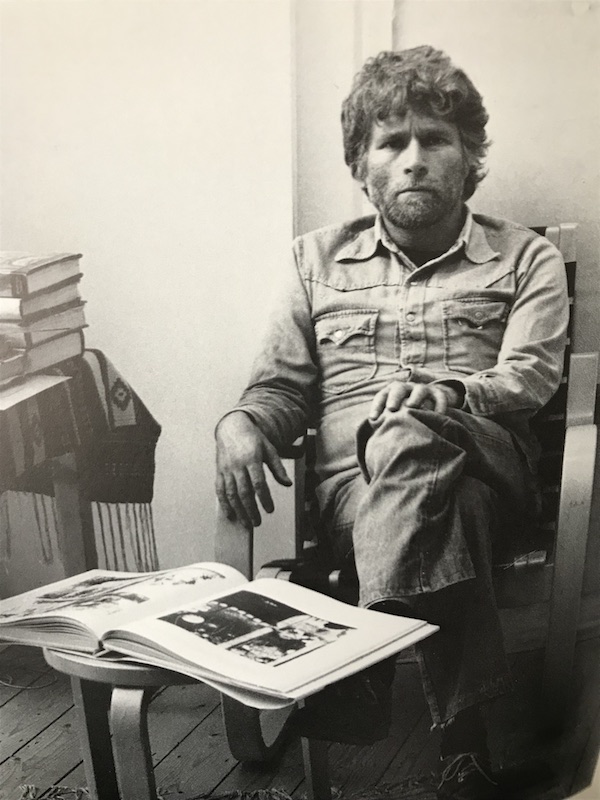

A striking thing about Kitaj is the way he and his work seem to have vanished from sight since his death – ELS

Three things emerge from the text. One is, as the title suggests, is his obsession with his own Jewishness. Another is his lasting resentment at the critical attacks on his retrospective at the Tate in 1994, which caused him to shake the dust of Britain, where he had long been resident, from his feet. He went so far as to blame these critical attacks for the sudden death of his beloved second wife, Sandra Fisher. His first wife, Elsi Roessler, committed suicide. The third thing – ‘emerge’ here being the right word – is Kitaj’s lifelong inability to keep his dick in his pants, even during the years of his marriage to Sandra, who seems to have accepted this characteristic with a certain equanimity. Paid for sex or unpaid, it doesn’t seem to have mattered too much. In this respect, he seems to have identified himself with the whoring giants of the Ecole de Paris, among them Giacometti.

A striking thing about Kitaj is the way he and his work seem to have vanished from sight since his death – a suicide like his first wife – in 2007. This is not the case with the galaxy of British figurative artists who surrounded him, many of whom – Freud, Auerbach, Bomberg, Kossoff – were Jewish-identified, like himself.

I knew Kitaj, briefly but quite well, during the latter part of the 1970s, when he was living a prosperous life in London, surrounded by a very small circle of friends, among them Vera Russell, a terrifying Russian, once an actress and fairly recently divorced from John Russell, art-critic of the London Sunday Times, who departed for greener pastures in New York in 1974. During that time, Kitaj made a rather good profile portrait of me. I wonder where it is now? We fell out of touch because I had a family crisis at the end of the 1970s, which lasted into the early 1980s. This put paid to any extra socialising in favour of obligatory hospital visits and the travails of moving house. Though I was already doing stuff as a critic, there was never a cross word between Kitaj and myself during this reasonably brief acquaintanceship.

I did go to the opening of Kitaj’s ill-fated Tate retrospective in 1994, accompanied by a woman friend, Hungarian-Jewish, a painter, and a great fan of his without knowing him personally. We progressed comfortably through the first two galleries, and then our admiration crashed, shipwrecked by one rather pretentious explanatory text after another – the artist’s ‘observations’ as he called them – posted side by side with the paintings. Zsusi kept clutching my arm and exclaiming: “Oh Ted, I’m so disappointed!” We were glad to get away, and later on, I felt profoundly grateful that I didn’t have to review the show. Had I done so, I would no doubt have rated an excoriating mention in the autobiography I am discussing here.

Later still, reflecting, I thought the bad reviews were provoked by two things. First, by those pretentious texts, telling the viewer what to think. Second, maybe even more so, by a series of interviews with female journalists, published in advance of the exhibition. The main theme of these was Kitaj as homme fatal, in the French vernacular sense of that phrase. The basic message was “I wanted to lie down then and there, and let this sexy artist tickle my tummy.” No wonder the reviewers, all male in those days, felt pre-empted and were correspondingly irritated.

The odd thing was that these hostile reviews seemed to make no difference to an already well-established career. Success came to Kitaj with remarkable rapidity once he moved to Britain in 1959 and enrolled at the Royal College of Art, where he teamed up, initially as a sort of father-figure, with David Hockney. He had his first solo show at Marlborough in 1963, took part in Documenta 3 and the Venice Biennale in 1964, and had a solo at Marlborough-Gerson in New York in 1965. In that same year, one of his paintings was purchased for the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

He established a reputation as a curator in the 1970s/early 1980s, with the Human Clay show for the British Council in 1975, and the Artist’s Eye for London’s National Gallery in 1980. There was a major retrospective at the Hirshhorn in Washington in 1981/2, which continued to Cleveland and Dusseldorf. The ill-fated retrospective at the Tate in 1994 continued to the Los Angeles County Museum in California and to the Metropolitan Museum, at both of which it had a much more favourable critical reception. In 1995 he was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale.

In 1997, after his move to Los Angeles, in disgust with the British art world, his international success continued. At least for a while. In 1998 a retrospective entitled An American in Europe toured from the Astrup Fearnley in Oslo to the Reina Sofia in Madrid, the Jewish Museum in Vienna and the Sprengel Museum in Hanover.

The problem was, I think, that, based as he now was in California, and increasingly reclusive, he never became the central figure in the United States that he had been in Britain. New York was still, though by that time precariously, the centre of the American art world and he didn’t belong. There were lions in American art who were both bigger than he was and could roar louder than he was now able to do.

Declining health was a factor. He was suffering from multiple sclerosis and increasingly unable to work on a large scale. No wonder he gave up.

I remember him saying to me in the days when I knew him, rather pretentiously and with suitably baited breath: “I wonder what my late style will be like?” The implication was that he would enjoy an experimentally radical and glorious old age like that of Titian or Rembrandt – though Rembrandt didn’t, in fact, get to be so old. It wasn’t to be.

This doesn’t alter the fact that, as this autobiography shows, Kitaj deserves a much bigger reputation than he seems to have now. Not least, because as he knew, and sometimes boasted, he was one of the best draughtsmen of his time. Good drawers are a lot rarer than good painters.

Words: Edward Lucie-Smith Top Photo P C Robinson © Artlyst 2018

R.B. Kitaj Confessions of an Old Jewish Painter Schirmer/Mosel £36