The Design Museum’s new exhibition, Imagine Moscow: Architecture, Propaganda, Revolution, is in many respects a great improvement on its rather incoherent opening show (or collection of shows). It offers a timely look at the impact made by the Russian Revolution of 1917, and at what happened to doctrinaire Soviet building projects in the years that immediately followed. In this basic fashion, it offers a good partner to the Revolution show now at the Royal Academy, though there, it must be said, the message is both more complex and a great deal subtler.

The basic, inescapable fact is that, of the seven major architectural projects featured in the show, only one reached completion, and then not in the full form originally intended. This exception to the general run of things is Lenin’s tomb, where the corpse of the Bolshevik leader is preserved, and still displayed (but for how long?) like that of a Christian saint. Visitors still wait in line to see the body, though the line is less long than it was in Soviet times. Wikipedia reports: “Visitors are required to show respect while in the tomb: photography and videotaping inside the mausoleum are forbidden, as is talking, smoking, keeping hands in pockets, or wearing hats (unless female).” Pray hard enough to St Vlad the Marxist, and he might be able to work a miracle for you.

‘What resonates today is the sheer un-realism of all these schemes’

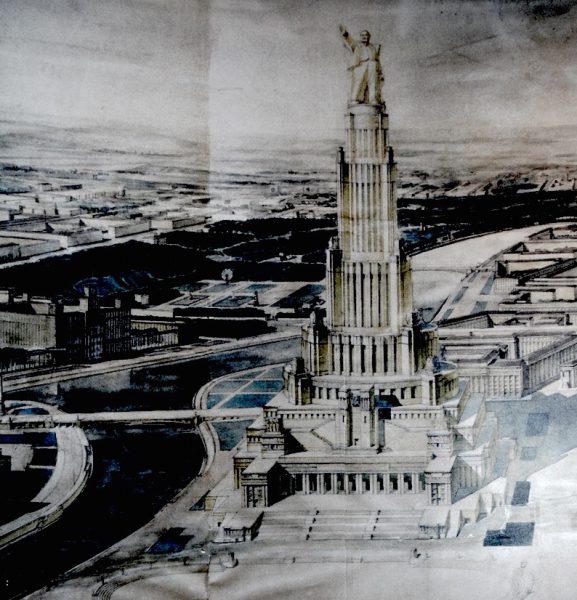

None of the other six projects exists in any recognisable form today. The site in Moscow intended for one of them, a gigantic Palace of the Soviets, was originally occupied by the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, built in the 19th century. This was pulled down in 1931 to make way for a vast new building – a model for it was shown at the Paris World Exposition 1937. Construction started that year but was halted by the German invasion of 1941.After that the site for a while lay more or less desolate – at one point it was occupied by a swimming pool. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the cathedral was rebuilt, in something closely resembling its original form. This sequence of events offers a verdict in itself.

In general, these aborted building projects reflected a determination to remake and transform Russian society, shared both by visionary Futurists and by the new rulers of Russia., though the latter turned out to have very different ideas about how the wished-for results might, in fact, be achieved. Among the dreams that never came to fruition was one for a Lenin Institute – a monumental central library intended to hold fifteen million books, which would transform a society many of whose members were still illiterate. There was also be a Health Factory on the shores of the Black Sea, dedicated to the idea of productive rest. A USSR Conference on Workers’ Vacations declared: “Like a machine, a person needs repair and recuperation; Socialist leisure restores the Proletarian machine-body.”

There was, too, a project for a Communal House, that would merge individual units into a single space, abolishing traditional family structures. As the catalogue for the show tells one:

“Communal kitchens and nurseries were [to be] introduced so that women could dedicate their free time to self-improvement. The emancipation of women was ultimately aimed at adding women to the workplace, one of the cornerstones of the new economic model of the Soviet Union.”

While I’m sure that at least some of these ideas resonate with visionary leftists today, the fact is that none of them worked in Soviet Russia, either in the short or the long term. What’s left is what one sees at the Design Museum – a lot of rather seductive graphic materials: posters, plans, architects’ drawings. Plus, tucked into a corner, a gigantic version of Lenin’s minatory forefinger, intended for a colossal statue that was never produced.

What resonates today is the sheer un-realism of all these schemes, which are comparable with Leonardo da Vinci’s seductive drawings of flying machine that would never have been able to fly. In the age on Brexit and of President Trump’s plans to revolutionise the provision of American healthcare and run American society without a continuing flow immigrants, either temporary or permanent, the show also, in a broader sense, seems right up to the minute.

Imagine Moscow: Architecture, Propaganda, Revolution Design Museum 15 March – 4 June 2017 Adult £10