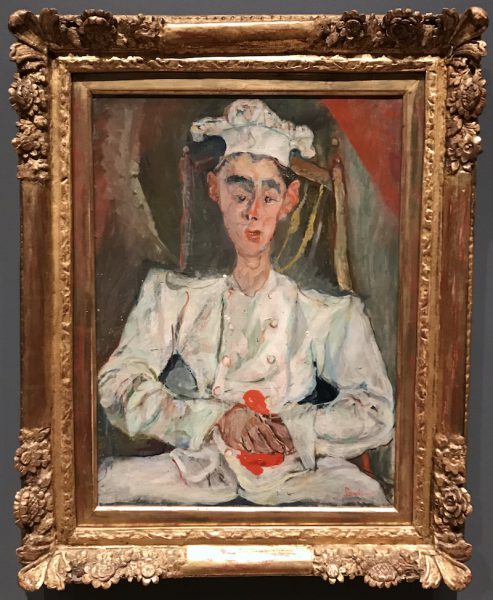

This compact, high-quality exhibition at the Courtauld offers a fascinating sociological and psychological puzzle. Entitled Soutine’s Portraits, and subtitled Cooks, Waiters and Bellboys, it features members of the inter-war underclass – specifically those who worked in the grand hotels and restaurants of Paris, with a few – females in this case rather than males – who worked in wealthy private households.

Portraits of servants and domestic workers were not new in European art. Usually, they appear in what are now classified by art historians as genre scenes. It is their activity that counts, rather than any attempt to discover a singular, specific human essence. There are just a few exceptions – for example, Orpen’s boldly confident, Velazquez-like Le Chef de l’Hotel Chatham Paris, painted c. 1921 – that is, very soon after Soutine produced the very first of his Pastry Cook paintings, usually dated c. 1919 and now in the collection of the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia. The two images could scarcely be more different regarding actual handling, but both seem to mark a sociological shift. They mark the point when cooks in grand hotels and restaurants became personalities in their own right.

Soutine was born poor and Jewish, in what is now Belarus, the tenth of eleven children. He studied art in Vilnius, Lithuania, and in 1913, aged twenty, migrated to Paris, like many aspiring artists from Eastern Europe and elsewhere. For a while, he shared quarters at La Ruche with Amadeo Modigliani, also Jewish. During this epoch, he attracted the attention of two major dealers, first Léopold Zborowski, then Paul Guillaume, but remained desperately poor. Until that is, he attracted the attention of the great American collector, Albert C. Barnes, who bought sixty paintings, all in one go. After this Soutine was never poor, though he seems to have remained rather isolated socially.

The series of portraits exhibited at the Courtauld represents a large majority of what he did when tackling this very particular category of subject-matter. Only two of them, a Butcher Boy painted c. 1919 and a Little Pastry Cook, painted c. 1921, belong to the period when he was still poor.

One as to ask oneself, what sort of message the series conveys, while recognising that the text may not have been wholly recognisable to the artist himself.

It is clear that the paintings were made direct from the model, long hours of confrontation in the artist’s studio, not in the places where the sitters worked. They sometimes depict the same individual, on separate canvases, several times over. The Courtauld how offers four different portraits of a single red-headed sitter, always seen frontally and wearing the same uniform. Soutine does not seem to have supplied titles to his pictures, and the different titles now attached to these canvases give some idea of the different atmosphere that each conveys. They are, respectively: Head Waiter (also known as Hotel Manager; Valet (also known as Hotel Boy); Room Service Waiter, and simply – once again – Valet. That is, the individual shown has been instinctively placed in three different hierarchies within the elaborate structure of grand hotel employment. Who he is may be the same; what he is, in each image, is subtly different.

As the catalogue points out, Francis Bacon did the same kind of repetitive thing with some of his major sitters – George Dyer, Isabel Rawsthorne, Henrietta Moraes. However, Soutine doesn’t seem to have cultivated this kind of intense personal relationship.

Nor is there quite the same dialogue one sees, in Soutine’s art as well as in Bacon’s, with established masterpieces of the past – in Soutine’s case, there is the series of variants on Rembrandt’s Flayed Ox. In Bacon’s, there are the numerous Popes, based on Velazquez’s portrait of Innocent X.

The other issue that interests me here is that all the domestic personnel shown are identified not just by their features, rendered with daring subjectivity, but by their uniforms. The catalogue tries to make something of this, pointing out that the chef’s hat sported by one of the sitters somehow resembles a crown, and that, in addition, one of the portraits has strong likeness to Fouquet’s famous portrait of Charles VII of France (1445-50), while the king’s red jacket is strangely reminiscent of the clothing worn by a Soutine Bellboy.

For me, what all this adds up to is the fact that these portraits, these intense examinations of individuals who can all be seen as members of a hierarchy – a cosmopolitan hierarchy only fully established in Soutine’s lifetime, the economy of the Grand Hotel – are also a metaphor, in negative form, for the painter’s own isolation. What Soutine found in the life of hotels, and in the grand country houses belonging to patrons that he also sometimes frequented, was the certainty that he belonged nowhere.

Words: Edward Lucie-Smith Photos: P C Robinson © Artlyst 2017

Soutine’s Portraits: Cooks, Waiters and Bellboys Courtauld Gallery London Until 21 January 2018

Visit Exhibition Here