There are very few cultural objects that carry the weight of an established myth. Fewer still that can be rolled up, placed in a crate, and sent across the Channel under armed guard. The Bayeux Tapestry is one of them — and next year, it will arrive in London under a Government indemnity estimated at £800 million.

The Treasury has confirmed it will underwrite the medieval embroidery while it is on loan to the British Museum, marking the first time the work has crossed the Channel in nearly a millennium. The agreement, years in the making, is part of a cultural exchange brokered at the state level between the UK and France. Politics, history, symbolism — all stitched tightly together.

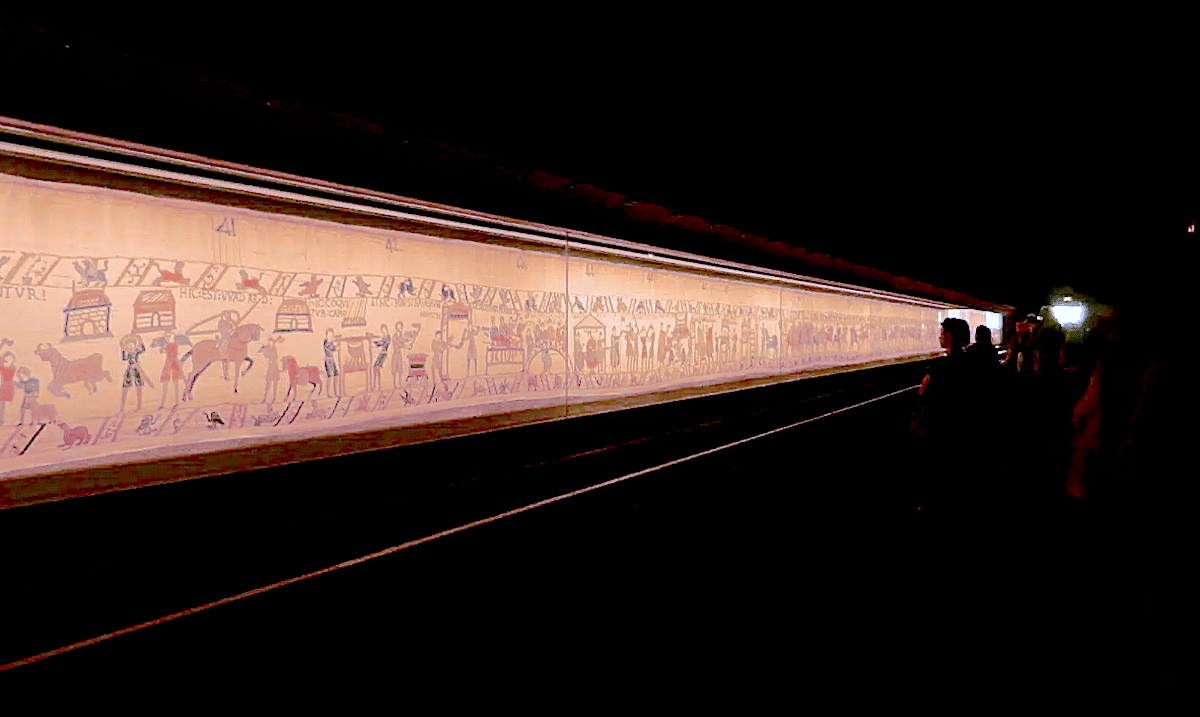

Measuring just over 70 metres long, the Bayeux Tapestry is an early piece of propaganda telling a story entwined with French and English history. It covers the Battle of Hastings in 1066, from Harold Godwinson’s oath to William of Normandy’s victory and coronation—horses rear. Ships land. Men die. Power changes hands. The English lose, BTW.

“Its survival alone is remarkable. That it will now be transported, insured, displayed and publicly scrutinised in London is something else entirely.”

The Treasury’s involvement comes via the Government Indemnity Scheme, a long-standing arrangement that allows major works to travel without museums having to shoulder vast commercial insurance premiums. The scheme will cover the tapestry during transit, storage and display, effectively placing the British state behind the object should anything go wrong.

Without the scheme, officials admit, the loan would be financially impossible. Commercial insurance on an object of this status would be prohibitive — and, frankly, absurd. This is not a painting you can replace or restore without consequence. Damage would be historic, not just material.

The final valuation has yet to be formally signed off, but figures circulating within government place it at around £800 million. The Treasury has not challenged that number. It hasn’t needed to. Not everyone is convinced the journey should happen at all.

In France, several conservators and historians have raised concerns about the tapestry’s condition, arguing that a work approaching its thousandth birthday should not be moved under any circumstances. French officials, however, have insisted that the tapestry has been thoroughly assessed and can travel safely under the strict temperature and humidity controls.

The weighing up of tensions between and risk sits at the heart of this loan. The tapestry will be shown in the British Museum’s Sainsbury Exhibitions Gallery from September next year until July 2027, while its home in Bayeux undergoes renovation. The timing is neat. The symbolism is less so. This is a French-held object depicting the conquest of England, returning — briefly — to the country it helped redefine.

It remains one of the most detailed visual records of medieval life ever made: 58 scenes, more than 600 human figures, over 200 horses, ships, weapons, feasts, executions. It is history rendered not in marble or oil paint, but in wool and linen. Narrative without commentary. Power without apology.

The indemnity scheme itself is often used in special circumstances. Its impact is substantial. Since its creation in 1980, it has enabled a number of major loans that would otherwise not happened. Museums save tens of millions each year through their use, allowing public access to works that might otherwise remain locked behind national borders or private vaults.

In return for the Bayeux loan, the British Museum will send objects to France that carry their own symbolic charge. Among them are artefacts from Sutton Hoo — material tied to early English kingship — and the Lewis chess pieces, those iconic medieval figures carved from walrus ivory.

What remains striking is how much this loan still matters. Nearly a thousand years on, the Bayeux Tapestry can still provoke anxiety, pride, resistance, and desire. It tells a story about who won — and who gets to remember. When the tapestry arrives at the British Museum, it will be one of the most important cultural exchanges of the century.

Top Photo: Beat Ruest Wiki Media Commons