Ahead of his solo show at Grimm’s London space (5 March – 18 April), you can see two recent paintings by the Dutch-born, London-based artist Michael Raedecker in ‘Connecting Threads’ at GPS Gallery in Soho. The show deals with the interface between textiles and other media: consistent with that, Raedecker blends painting with richly textural embroidery, resisting the perceived distinctions between ‘fine art’ and craft, and conjuring scenes that hold the urban in an uneasy balance with nature. How did he arrive at his distinctive practice?

You make paintings in unusual ways. How did that start?

When I was studying fashion design at the art academy in Amsterdam in the late 1980s, I remember a dispute and uprising in the painting department. The students were frustrated by the tedious still-life studies in oil paint and the meticulous portrait sessions in life-model classes. What they really wanted was to paint whatever they wanted. However, the teachers insisted that they had the rest of their lives to do that—at the academy, they were there to learn essential techniques. I understood both perspectives: the need for creative freedom and the value of mastering technique. A compelling statement about artistic training and technique is that one goes to art school for five years to learn, and then needs another five years to ‘unlearn.’

Around that time, I accidentally ‘invented’ a transfer technique—a lo-fi, DIY method using A3 laser printer photocopies. I would glue A3 sheets onto the canvas, let them dry, then rub and remove the paper until only the pigment remained. It was monotonous, hard work—especially the rubbing—but the result felt like magic every time. By the time I graduated with a B.A. in Fashion Design, I knew I had to change course and become a painter. The first question I asked myself was: What am I going to paint? And more importantly, how am I going to paint? Painters painting with paint had been done for hundreds of years, and I was not interested in following that same method—I wasn’t drawn to the act of painting itself. Instead, I was intrigued by alternative methods for arriving at the finished image.

And then Winston Churchill, who has a 50-work retrospective at the Wallace Collection running 23 May – 29 November this year, played a surprising role?

During a visit to the local library, I came across a book on Winston Churchill’s paintings. I had never known the renowned statesman was an avid amateur painter. He took his hobby seriously for over forty years and even wrote an essay titled Painting as a Pastime, where he emphasised his passion and the joys of painting outdoors. This struck a chord with me—the idea of painting purely for enjoyment wasn’t embraced in the art world, which made me want to explore it in a tongue-in-cheek way.

I became interested in examining painting as a historical medium through the lens of the ‘Sunday painter’—someone who paints for pleasure, without an agenda. I wanted to escape the tradition of painting by introducing a deliberately ‘wrong’ element. I chose embroidery—a craft, a hobby, a pastime—a medium without ideology—and combined it with the transfer technique. This contrast between ‘high’ art (painting) and ‘low’ craft (needlework) led me to create my first paintings. I selected some of Churchill’s paintings, transferred them onto canvas, and stitched details, such as the work’s title, in colours that matched the print.

What appealed to you about the threading technique?

I appreciated the effort required and enjoyed working with it. At first glance, it might appear provocatively conservative, but its simplicity fascinated me. Stitching with a needle and thread is one of the easiest techniques: puncturing the surface, pulling the thread through, and repeating. The needle moves front to back, back to front, front to back, back to front—a timeline zig-zagging through the canvas. I love threading my paintings when the needle goes in and out, in and out, in and out, in and out. This can be a stitch of a millimetre or as big as the size of the canvas. The repetition was meditative—penetrating the linen again and again, again and again, again and again, again and again. This craft aims to attract and puzzle the viewer and creates an ideal interplay between the high and the low, the banal and the original, the everyday and the uncanny. A stitch both reveals and conceals; what remains unseen is often more significant than what is visible.

You moved away from transfers for some years. Why was that?

After working with transfers and embroidery for a couple of years, I began to feel the limitations of using pre-existing images from books and magazines. This was before digital tools were widely available, and I wanted to compose my own images. I decided to drop the transfers, introduce paint, and keep the stitching. For the next twenty-five years, these materials defined my practice.

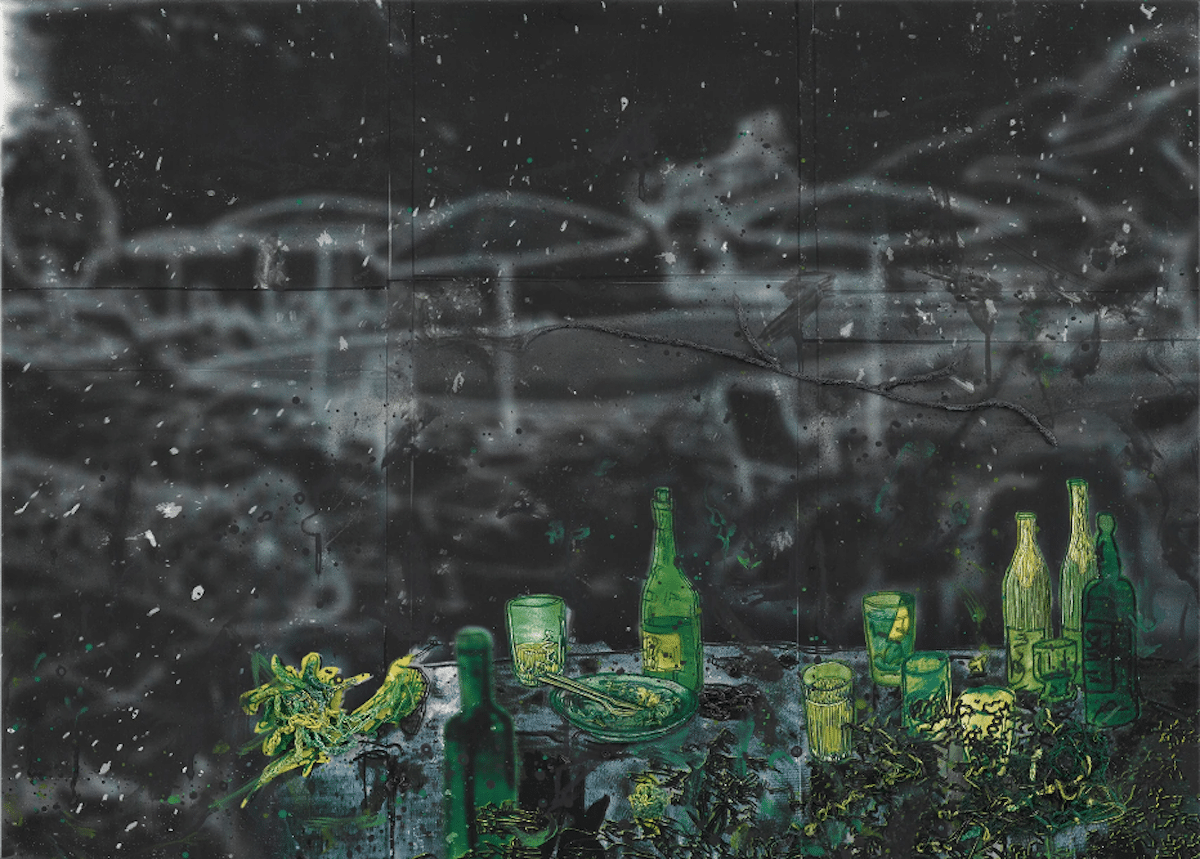

I used paint to establish tone and atmosphere rather than to create detailed imagery. I painted quickly using large brushes to cover the canvas in monochromatic washes. I avoided virtuoso brushwork and instead found ways to subvert traditional figuration—pouring paint to mimic rippling water, layering shades to suggest rocky landscapes. Initially, I used household paints for their ready-mixed colours but later switched to high-quality acrylics for durability. I never used oils as they didn’t work well with thread and took too long to dry.

But now you have returned to the transfer technique?

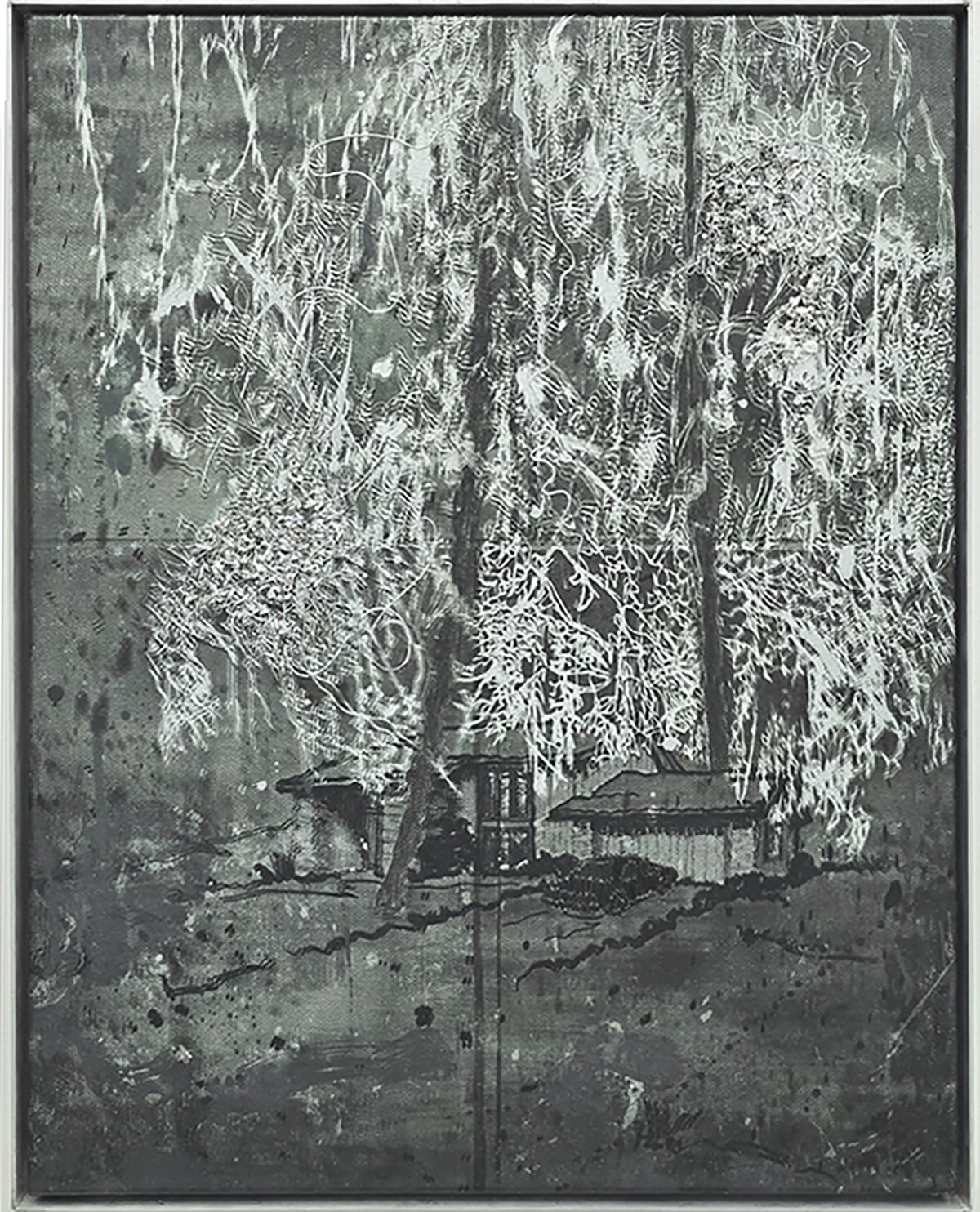

About six or seven years ago, yes. By then, I had worked with a computer for many years to prepare sketches and compositions in Photoshop, giving me complete control over my images. My process now starts with a hand-drawn sketch, which I develop on canvas with thread and paint. I photograph the work, discard the original, and rework the image digitally. After multiple test prints,s the final composition is transferred onto canvas. Two layers of the same image are printed on top of each other, however, never fully aligning, obscuring the boundaries between paint, print, and stitch. I sometimes paint beneath or over the transfer, finishing the piece with embroidery. Recently, I have been exploring classic craft techniques like crocheting, knitting, and weaving, incorporating fabric cut-outs, beads, and sequins. I occasionally enlist an assistant to prepare these elements before attaching them to the canvas.

Up close, my work is all material—thread behaving as pigment, transfers resembling paint. Stepping back, decoration becomes figuration, and materials blend into imagery. My paintings are not just pictures; they are built from overlapping processes and materials. I enjoy playing with layering to construct a painting, where each separate element is insufficient on its own, but together they create an engaging composition. After all these years, I remain fascinated by how a painting is made—more than by what it depicts.

Yet your what is also interesting… You have described yourself as dealing with our confrontation with nature. Could you expand on that?

We did not choose to be here; we did not have anything to say in the matter. Earth, nature, and the landscape have been here long before us, and will be here long after we are gone. We have to deal with nature, but nature does not deal with us; it is just doing its own thing.

Human superiority, intelligence and arrogance found an impressive way to inhabit and conquer earth – to create humanity and achieve a quality of life. However, existentially, we are still trying to get used to being here, not always knowing whether we even belong here. Not always able to express what we really want, or to say what we really mean.

Throughout the thirty years of my practise I have made works that deal with this confrontation, alliance, symbiosis of us versus nature – our place in this world. The visualisation of these themes goes hand in hand with my cultural background, where I am living and in what time. And also, the type of medium I use to express myself.

Has that remained similar?

Looking back, the enormous variety of events and developments experienced over these last thirty years has naturally seeped in. Questioning life, myself, and society. And next to that, painting; not only the what, but more, the how to paint.

My paintings deal with the presence, but the visual absence of us in relation to our environment, indoors and outdoors. The suburban setting where the landscape meets man-made dwellings, the proximity and power of nature in relation to the urban environment. Where we live, the exterior and the interior, and the variety of items we gather to make our living environment personal and homely. Observing, playing, translating, and finding an awareness of ‘where’ we exist. The familiar with the alien, the banal with the profound, the ordinary with the incomprehensible.

All Images courtesy the artist and Grimm Gallery. Top Photo: Michael Raedecker with ‘common chaos’, 2022 – Laser printer pigment transfer, dispersion, acrylic and thread on canvas, 140 x 185 cm

‘back drop’ and ‘demo (quiet boom – silver)’ are included in ‘Connecting Threads’ at the GPS Gallery, 36 Great Pulteney Street, Soho – 8 -17 January 2026. Michael Raedecker’s solo show will run at Grimm, 43a Duke Street, St. James’s, 5 March – 18 April