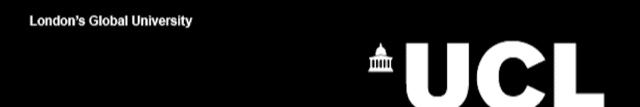

Jewish Dealers And The European Art Market c. 1860-1940 – Clare Finn

Jewish Dealers and the European Art Market, c. 1860-1940, negotiating cultural modernity, Ed’s. Silvia Davoli & Tom Stammers, Bloomsbury Visual Arts, London, New York, Oxford, New Delhi, Sydney, 2025 – in the series ‘Contextualising Art Markets’.

Few interested in the history of early modernist painting can be unaware of the contributions Jewish dealers made to promoting and supporting its artists; Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, Berthe Weil, both Leone and Paul Rosenberg, Alfred Flechtheim, Alfred Stieglitz, are but a few. Why the jews? Why not others?

This publication begins with an extended introduction that focuses on how methods, interpretations, and biases regarding these questions have changed over time. In 1912, Moritz Goldstein insisted, controversially, that without Jewish contributions, there would have been no modern culture in Germany at all. Shortly after this, in 1919, Thorstein Veblen wrote his ‘The Intellectual Pre-Eminence of Jews in Modern Europe’ in which he maintained that being on the margins gave Jews more objectivity. Following World War II and the Holocaust, the significance of these Jewish firms has rarely been considered outside the context of Nazi persecution.

In this book, a wider, longer view moves the focus away from the 1930s and 1940s and Jewish victimhood. Structured in a series of essays by its eighteen academic contributors, it draws on a great deal of more recent, secondary literature. They look into Jewish history, studying the dynamism and inventiveness of Jewish businesses from the mid-19th century, and noting the growth of the modern art market and the shift of the arts from the Royal Court into the metropolis. The spread of Jewish political and legal emancipation refers to the extension of civil rights to Jews and their rapid acculturation into European society.

They reject the idea that there are more Jewish dealerships, numerically speaking, than non-Jewish ones. Nor were Jewish business methods radically different from those of other non-Jewish dealers. On this, some more detailed comparisons would have been welcome. Rather than asking what Jews did differently from non-Jews, new histories ask why Jews were structurally well placed to seize opportunities created by expanding markets. Timing mattered: in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jews migrated to Metropolitan centres, hubs of the art market and crucibles of the avant-garde. Changes, both social and artistic, provided opportunities for new players, including Jews. Had they arrived in Berlin, Paris, Vienna or London decades later, they would’ve had little or no opportunity to play their part as creators or champions of modern Art. Charles Dellheim, author of Belonging and Betrayal: How Jews Made the Art World Modern and of this book’s Afterword, assessed Art dealing as a good fit for Jews. It was a rapidly expanding field with few barriers, required modest capital investment, and offered opportunities to develop international trade and geographical mobility. Thus, Jews who dealt and collected gained acculturation, a source of wealth, and a mark of status.

The ability of Jews, the ‘people of the book’, to make their mark as art dealers, collectors, critics, historians, and artists depended on diverse factors. Nearly all of those I wrote about, states Dellheim, were migrants or immigrants, commercial or financial men who used the skills, habits and contacts acquired in more ordinary businesses in the world of Art. Migrant contacts in the logistics, brokerage, and shipping sectors were beneficial for importing non-European goods.

Before becoming art dealers, Jews were known as assessors of the value of many luxury items: feathers, diamonds, metals, and horses. Before becoming dealers in paintings, Nathan Wildenstein was a trader in horses; Paul Rosenberg’s father was a cereal dealer; Joseph Joel Duveen, arriving in Hull from the Netherlands, started as a general dealer specialising in Nanking porcelain; Kahnweiler came from a background in commerce. All brought skills gained in other trades to the market for Art.

Selling works of Art turns on highly subjective criteria of value. Such transactions are not anonymous but are made through a web of interpersonal relationships, “in which the credibility of the dealer is inextricably caught up with a perceived quality of the merchandise”. Art dealing represented the union of two historic Jewish specialities, commerce and scholarship, in new ways. Credibility, however, could be disrupted by antisemitism, as illustrated by Fae Brauer’s essay on Kahnweiler, focusing on WWI.

In the 19th century, art dealing was not as specialised; dealers could sell furniture, decorative arts, curios, and paintings. Through case studies, this book demonstrates the role of the family in Jewish businesses, and before modernist Art, many were known for introducing Asian Art into Western Europe. They were essential mediators in uniting east and west, most obviously in the case of Japanese arts and the vogue for Chinese porcelain in the early 20th century, whether we think of Sigfried Bing and Phillipe Sichel in Paris, Edgar Gorer in London or Edgar Worsh, Felix Tikothin and Otto Burchard in Berlin.

This book leads the reader through themes, strategies and politics of prominent Jewish art businesses many of whose names and contributions are less familiar; Moisé Michelangelo Guggenheim in Venice (no relation to Peggy or Solomon), the Mannheims in Paris, Charles’ The Only Man in Europe’ Davis in London, the Samuel Family, and Florine Ebstein Langweil the latter two being prominent dealers in East Asian Art and Curios. This is before we reach Siegfried Bing and Julius Meier-Graefe, or those names known for promoting modernist Art: Kahnweiler, Léonce Rosenberg, Alfred Flechtheim, Gimpel Fils, and Martin Birnbaum. Not every Jewish dealer one may know of gets an essay to themselves; Paul Roseberg, the Wildensteins, Berthe Weill and others are mentioned but not dealt with in depth. Then there was the infamous rather than famous Leo Nardus and the Birtchansky Brothers, known for selling forgeries and pieces with more enthusiastic attributions than they warranted.

In its just over 300 pages, this well-referenced publication provides an excellent grounding on the subject and plenty of information for anyone wishing to dive deeper.

Jewish Dealers and the European Art Market, c. 1860-1940, negotiating cultural modernity, Ed’s. Silvia Davoli & Tom Stammers, Bloomsbury Visual Arts, London, New York, Oxford, New Delhi, Sydney, 2025 – in the series ‘Contextualising Art Markets’.

Few interested in the history of early modernist painting can be unaware of the contributions Jewish dealers made to promoting and supporting its artists; Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, Berthe Weil, both Leone and Paul Rosenberg, Alfred Flechtheim, Alfred Stieglitz, are but a few. Why the jews? Why not others?

This publication begins with an extended introduction that focuses on how methods, interpretations, and biases regarding these questions have changed over time. In 1912, Moritz Goldstein insisted, controversially, that without Jewish contributions, there would have been no modern culture in Germany at all. Shortly after this, in 1919, Thorstein Veblen wrote his ‘The Intellectual Pre-Eminence of Jews in Modern Europe’ in which he maintained that being on the margins gave Jews more objectivity. Following World War II and the Holocaust, the significance of these Jewish firms has rarely been considered outside the context of Nazi persecution.

In this book, a wider, longer view moves the focus away from the 1930s and 1940s and Jewish victimhood. Structured in a series of essays by its eighteen academic contributors, it draws on a great deal of more recent, secondary literature. They look into Jewish history, studying the dynamism and inventiveness of Jewish businesses from the mid-19th century, and noting the growth of the modern art market and the shift of the arts from the Royal Court into the metropolis. The spread of Jewish political and legal emancipation refers to the extension of civil rights to Jews and their rapid acculturation into European society.

They reject the idea that there are more Jewish dealerships, numerically speaking, than non-Jewish ones. Nor were Jewish business methods radically different from those of other non-Jewish dealers. On this, some more detailed comparisons would have been welcome. Rather than asking what Jews did differently from non-Jews, new histories ask why Jews were structurally well placed to seize opportunities created by expanding markets. Timing mattered: in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jews migrated to Metropolitan centres, hubs of the art market and crucibles of the avant-garde. Changes, both social and artistic, provided opportunities for new players, including Jews. Had they arrived in Berlin, Paris, Vienna or London decades later, they would’ve had little or no opportunity to play their part as creators or champions of modern Art. Charles Dellheim, author of Belonging and Betrayal: How Jews Made the Art World Modern and of this book’s Afterword, assessed Art dealing as a good fit for Jews. It was a rapidly expanding field with few barriers, required modest capital investment, and offered opportunities to develop international trade and geographical mobility. Thus, Jews who dealt and collected gained acculturation, a source of wealth, and a mark of status.

The ability of Jews, the ‘people of the book’, to make their mark as art dealers, collectors, critics, historians, and artists depended on diverse factors. Nearly all of those I wrote about, states Dellheim, were migrants or immigrants, commercial or financial men who used the skills, habits and contacts acquired in more ordinary businesses in the world of Art. Migrant contacts in the logistics, brokerage, and shipping sectors were beneficial for importing non-European goods.

Before becoming art dealers, Jews were known as assessors of the value of many luxury items: feathers, diamonds, metals, and horses. Before becoming dealers in paintings, Nathan Wildenstein was a trader in horses; Paul Rosenberg’s father was a cereal dealer; Joseph Joel Duveen, arriving in Hull from the Netherlands, started as a general dealer specialising in Nanking porcelain; Kahnweiler came from a background in commerce. All brought skills gained in other trades to the market for Art.

Selling works of Art turns on highly subjective criteria of value. Such transactions are not anonymous but are made through a web of interpersonal relationships, “in which the credibility of the dealer is inextricably caught up with a perceived quality of the merchandise”. Art dealing represented the union of two historic Jewish specialities, commerce and scholarship, in new ways. Credibility, however, could be disrupted by antisemitism, as illustrated by Fae Brauer’s essay on Kahnweiler, focusing on WWI.

In the 19th century, art dealing was not as specialised; dealers could sell furniture, decorative arts, curios, and paintings. Through case studies, this book demonstrates the role of the family in Jewish businesses, and before modernist Art, many were known for introducing Asian Art into Western Europe. They were essential mediators in uniting east and west, most obviously in the case of Japanese arts and the vogue for Chinese porcelain in the early 20th century, whether we think of Sigfried Bing and Phillipe Sichel in Paris, Edgar Gorer in London or Edgar Worsh, Felix Tikothin and Otto Burchard in Berlin.

This book leads the reader through themes, strategies and politics of prominent Jewish art businesses many of whose names and contributions are less familiar; Moisé Michelangelo Guggenheim in Venice (no relation to Peggy or Solomon), the Mannheims in Paris, Charles’ The Only Man in Europe’ Davis in London, the Samuel Family, and Florine Ebstein Langweil the latter two being prominent dealers in East Asian Art and Curios. This is before we reach Siegfried Bing and Julius Meier-Graefe, or those names known for promoting modernist Art: Kahnweiler, Léonce Rosenberg, Alfred Flechtheim, Gimpel Fils, and Martin Birnbaum. Not every Jewish dealer one may know of gets an essay to themselves; Paul Roseberg, the Wildensteins, Berthe Weill and others are mentioned but not dealt with in depth. Then there was the infamous rather than famous Leo Nardus and the Birtchansky Brothers, known for selling forgeries and pieces with more enthusiastic attributions than they warranted.

In its just over 300 pages, this well-referenced publication provides an excellent grounding on the subject and plenty of information for anyone wishing to dive deeper.