The Chinese zodiac turns once more to the Horse, but not just any horse. This year brings the rare Fire Horse, a volatile alignment that appears only once every 60 years. Tradition links it with heightened energy, restless movement, flashes of brilliance, and the occasional streak of recklessness. It’s a fitting moment, then, to look again at how artists across centuries have tried to capture the animal’s peculiar force its speed, its beauty, its unnerving presence, somewhere between companion and elemental power. Think of it instead as a loose stable of encounters: horses as symbols, as workers, as myth, as flesh and muscle and nervous energy a quick gallop through art history.

10) Horses of Lascaux Cave, France, c. 15,000–13,000 BC Long before oil paint or bronze monuments, horses were running across stone walls.

The caves at Lascaux in southwestern France, sometimes called the Sistine Chapel of prehistory, contain more than 300 equine images. They are astonishingly alive. Painted with charcoal and mineral pigments, these animals surge across limestone surfaces that seem to buckle and move beneath them. The artists used the natural contours of the cave walls to suggest swelling muscle or shifting weight. Nothing here feels static. The horses resemble stocky wild breeds, often identified with Przewalski’s Horse. They gallop, turn, and gather momentum. Some float in space; others emerge from darkness. Their purpose was likely ritual rather than decorative images bound up with survival, belief, and the rhythms of the hunt. Discovered by teenagers in 1940, the caves were later closed to protect them from human breath and light. Even in reproduction, though, the urgency remains. The Horse appears here not as subject, but as presence.

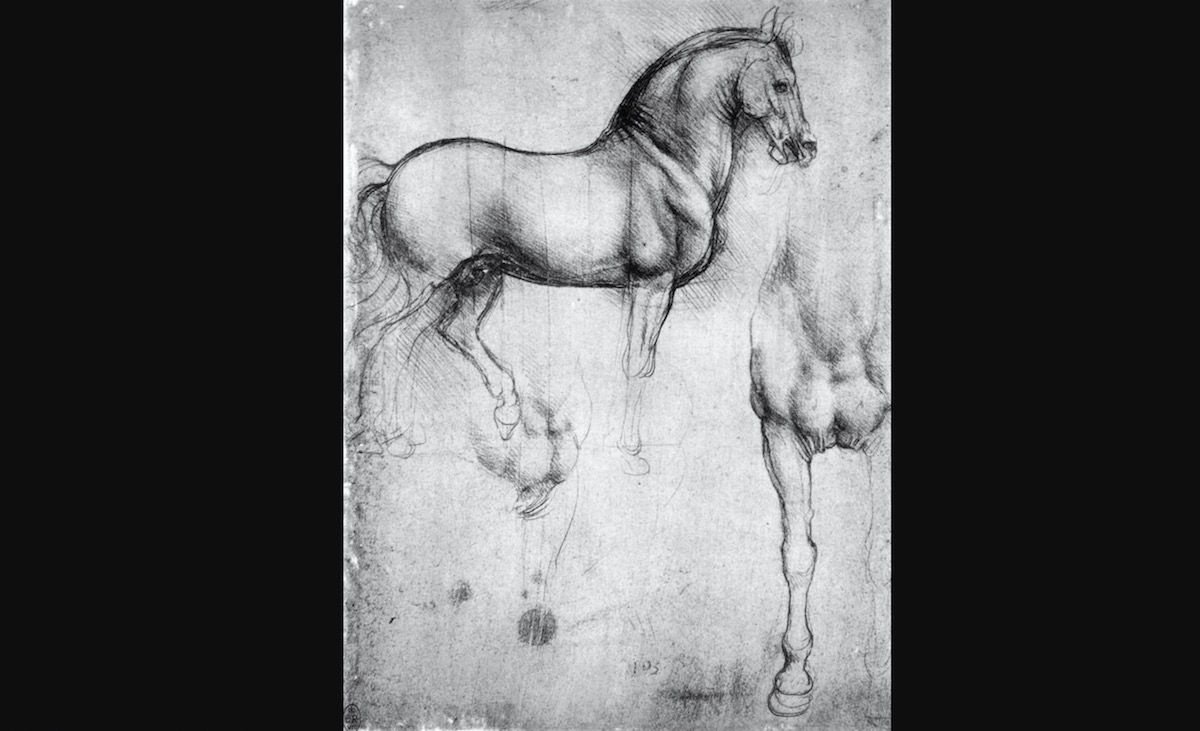

9) Leonardo da Vinci — Horse Studies (late 15th century)

Leonardo didn’t simply draw horses, he dissected them with his eyes. Across thousands of notebook pages, he studied the animal obsessively: the flex of tendons, the geometry of the skull, the blur of limbs in motion. A raised foreleg becomes a mechanical problem. A turning head, a matter of proportion. His aim was not symbolism but understanding the Horse as a biological engine. These investigations fed into his long and ultimately ill-fated project for the Sforza monument, planned as the world’s largest bronze equestrian statue. He worked on it for 16 years. The vast clay model was destroyed by French archers in 1499 before casting could begin. What survives are the drawings, restless, precise, almost trembling with curiosity. They remain among the most searching studies of animal movement ever made.

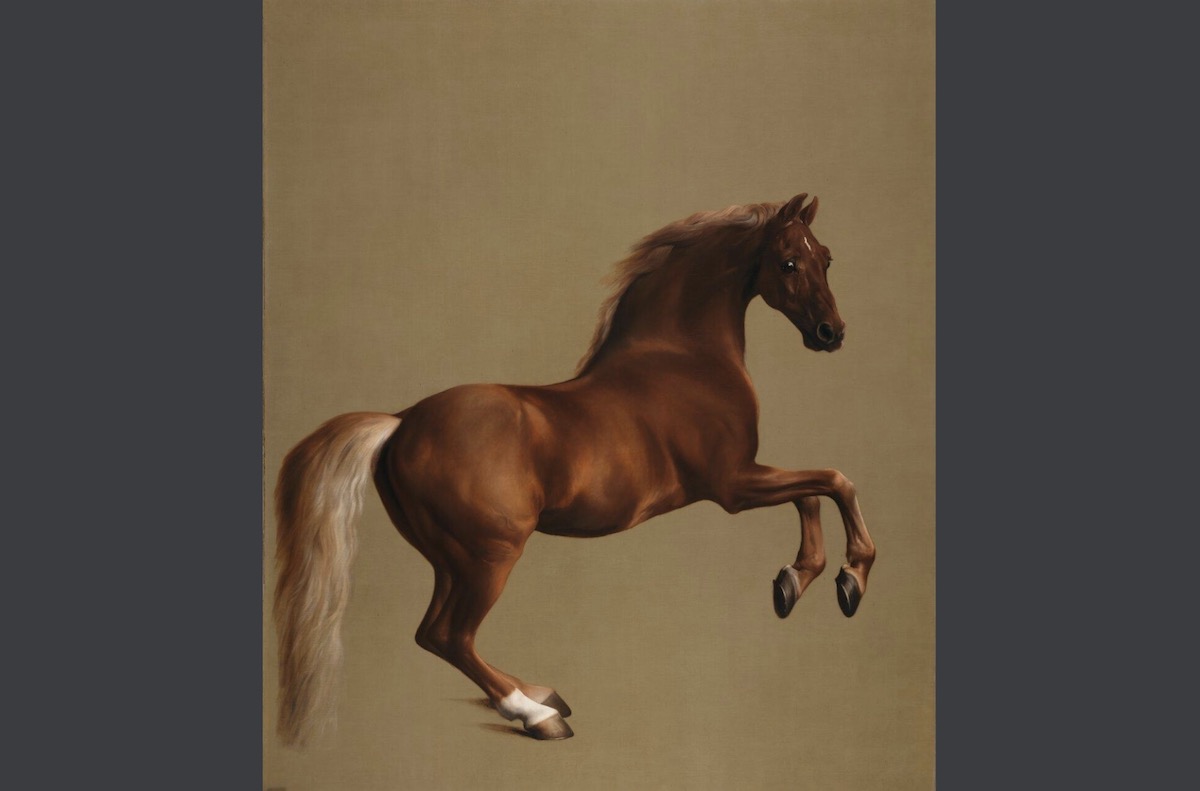

8) George Stubbs — Whistlejacket (1762) National Gallery, London

Few paintings confront you quite like Whistlejacket: no landscape, no rider, no narrative, just a stallion rearing against an empty ground. Stubbs, largely self-taught, studied equine anatomy with near-scientific dedication, even dissecting horses to understand their structure. Here, that knowledge translates into something startlingly direct. The animal seems to exist outside time or place, a pure embodiment of energy held in suspension. Commissioned by the Marquis of Rockingham, the painting carries all the prestige of 18th-century British horse culture. Yet it feels strangely modern, minimal, focused, almost abstract in its isolation of form. The Horse represents power.

7) Jacques-Louis David — Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1801)

History painting rarely resists drama, and David gives us plenty of it. Napoleon, cloak whipping in the wind, urges his rearing horse up a treacherous Alpine pass. The reality was apparently far less heroic; the general crossed the mountains on a mule, but accuracy was beside the point. This is propaganda, pure and confident. David painted multiple versions of the image, refining its theatrical force each time. Horse and rider fuse into a single symbol of command, ambition, and state power. Even now, the painting’s swagger is difficult to ignore. The Horse here becomes political theatre history rewritten at full gallop.

6) El Greco — Saint Martin and the Beggar (c. 1597–1600)

El Greco’s horses feel almost otherworldly. Limbs stretch, proportions elongate, colour shimmers strangely. In Saint Martin and the Beggar, the mounted saint divides his cloak to share with a destitute figure below. The Horse stands poised, elegant yet slightly unreal, its presence lending the scene spiritual gravity. Everything seems pulled upward, bodies, gestures, even light itself. The animal is not just a form of transport. It is part of the painting’s mysticism: a creature suspended between the earthly and the divine realms.

5) Edgar Degas — Horses Before the Stands (1866–68)

Degas loved the moments before action. His racehorses wait, shift weight, tremble with nervous anticipation. Influenced by early photography, including the motion studies of Eadweard Muybridge, Degas explored posture and movement with unusual precision. Figures cluster awkwardly; horses turn their heads unexpectedly. The compositions feel cropped, almost accidental. Nothing heroic here. Just tension in the air, the charged stillness before release.

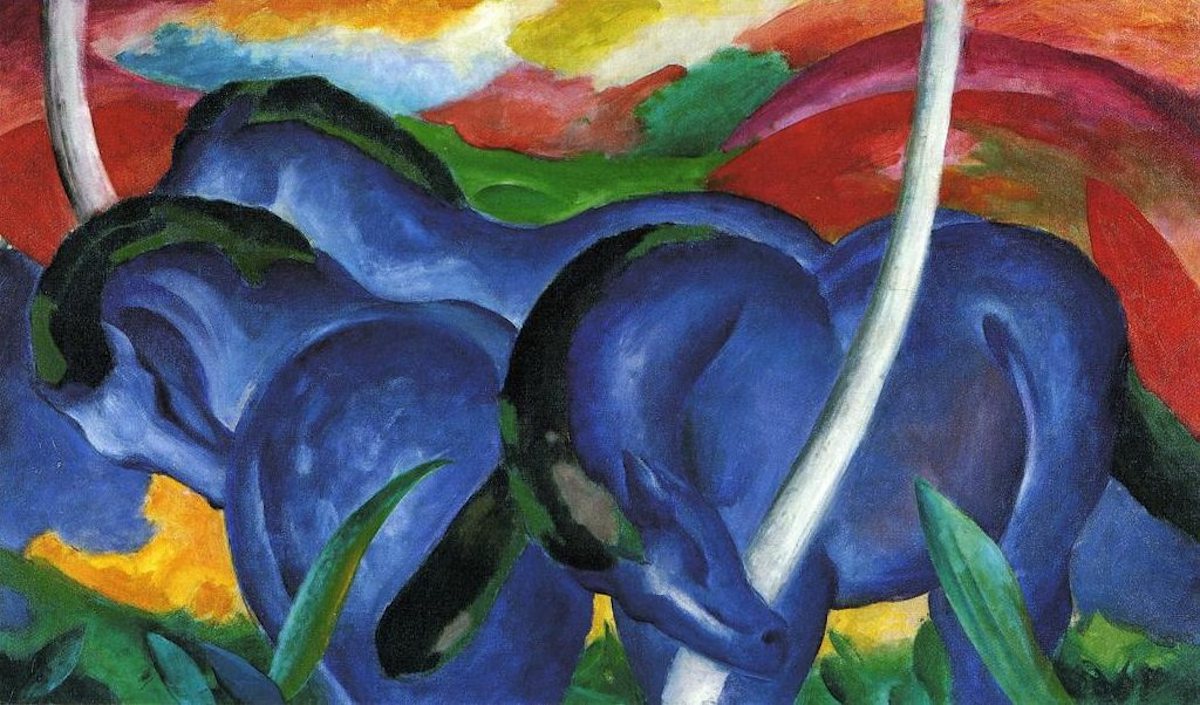

4) Franz Marc — Blue Horses I (1911)

Marc’s horses are not flesh-and-blood animals but vessels of feeling. Painted in luminous blues against fractured colour fields, they embody spiritual harmony and emotional intensity. Marc believed that colour carried symbolic meanings: blue for masculinity and spirituality, yellow for warmth, and red for violence. The result is both tender and strange. These horses exist in a world purified of human corruption, an ideal that the First World War would soon shatter.

3) Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec — Équestrienne (At the Cirque Fernando) (1887–88)

The circus ring is all theatre spectacle, balanced on risk. Toulouse-Lautrec captures a female rider preparing to leap through a hoop as her horse charges forward. The scene feels tense, almost confrontational. The rider’s painted face, the ringmaster’s glare, the animal’s speed everything pushes toward a moment that hasn’t yet happened. The Horse becomes an accomplice to performance, a partner in danger and display.

2) Elisabeth Frink — Horse Sitting (mid-late 20th century)

Frink’s horses feel ancient, heavy, scarred, and almost prehistoric in their presence. Whether sculpted in bronze or rendered in spare drawings, they carry an elemental dignity. She stripped forms down to essentials: mass, texture, stance. Her animals are not decorative but psychological, charged with tension and vulnerability. They exist in a state of watchfulness, poised between strength and fragility. It’s a powerful reminder that the Horse remains one of art’s most enduring mirrors of human emotion.

1) A Final Gallop

Eadweard Muybridge (born Edward James Muggeridge) was a pioneering English photographer whose work in the 1870s and 80s fundamentally reshaped our understanding of motion. Most famous for his study of a galloping horse, he used a complex system of tripwire-activated cameras to prove that all four hooves leave the ground simultaneously. This breakthrough not only settled a long-standing scientific debate but also led to his invention of the zoopraxiscope. This primitive motion-picture projector paved the way for the birth of cinema.

Beyond his scientific achievements, Muybridge led a life as dramatic as his photographs. After surviving a near-fatal stagecoach accident that some believe altered his personality, he gained notoriety for the 1874 murder of his wife’s lover—a crime for which he was later acquitted on the grounds of “justifiable homicide.” Despite this turmoil, his massive 11-volume compendium, Animal Locomotion, remains one of the most influential photographic works in history, serving as a vital bridge among fine art, Victorian science, and modern technology.

Across these works, from cave wall to white cube, the Horse persists as a subject that refuses to settle. It can be a divine messenger, a political emblem, a labouring companion, or an abstract form. It can embody velocity, endurance, vulnerability, and rage. The Fire Horse year is characterised by intensity and transformation. Artists, it seems, have been grappling with those same qualities for millennia — trying, again and again, to pin down something that is always moving.