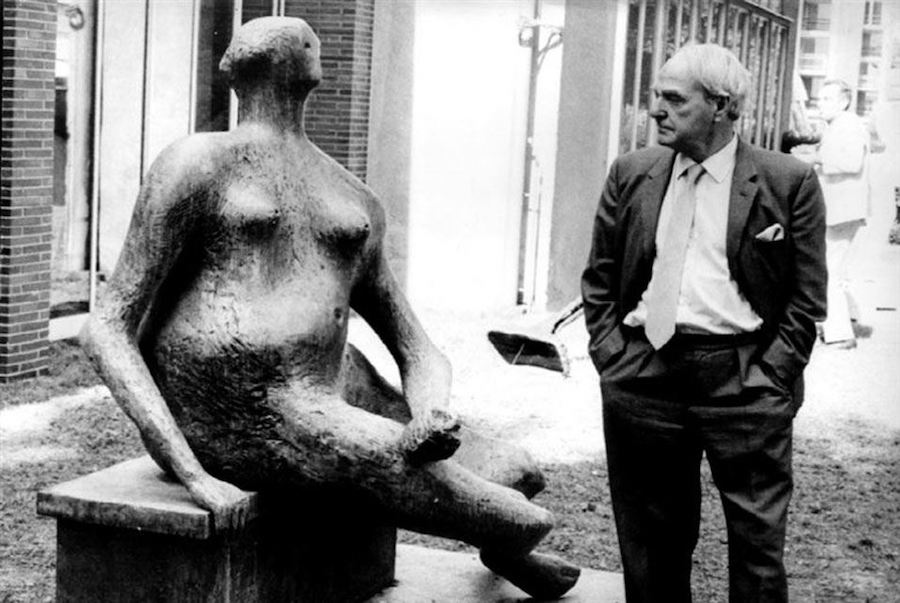

Henry Moore was born July 30, 1898 – Died August 31, 1986. The hulking, hollowed-out forms of Henry Moore’s sculptures have become as much a part of Britain’s visual identity as the rolling hills and chalk cliffs that inspired them. Born in 1898 in Castleford, a Yorkshire mining town, Moore grew up surrounded by industrial grit and ancient geology—a tension between artificial and organic that would define his life’s work.

His childhood was unremarkable but for two revelations: the texture of coal shale under his fingernails, and a teacher who introduced him to Michelangelo’s drawings. By 18, he was both a schoolteacher and a wounded veteran of the Somme, his lungs scarred by mustard gas. That brush with mortality sharpened his focus. “The war made me think an artist’s life wasn’t frivolous,” he later said. “It was urgent.”

Moore’s early years at Leeds School of Art and the Royal College were marked by rebellion. While tutors preached Neoclassical precision, he haunted the British Museum’s ethnographic collections, drawn to the blunt power of Aztec carvings and Cycladic figures. A 1924 trip to Paris cemented his heresies—Rodin’s tortured surfaces and Brancusi’s radical simplifications became his lodestars. By 1930, his first major solo show provoked outrage; critics called his abstracted mother-and-child figures “primitive” and “obscene.”

The 1940s transformed Moore from provocateur to national symbol. His wartime Shelter Drawings—ghostly images of Londoners huddled in Underground stations—caught the public imagination with their raw humanity. Commissioned as a war artist, he sketched miners at work, recognising in their bent postures the same “weight and endurance” as his sculptures. When his Hampstead studio was bombed in 1940, he relocated to Hertfordshire, where the rural landscape seeped into his work. Sheep skulls and flint stones joined his collection of natural objects, their shapes echoing in bronzes like Reclining Figure: Festival (1951), its pierced torso mirroring the wind-scoured hills.

Postwar fame brought monumental commissions: Knife Edge Two Piece (1962) for London’s Parliament Square, the UNESCO Reclining Figure (1957) in Paris. Critics accused him of repeating himself, but Moore never stopped experimenting. In his 70s, he embraced polystyrene maquettes, letting their lightweight forms guide his chisel. The Henry Moore Foundation, established in 1977, became both archive and workshop—a rare artist’s institution designed to outlive him.

Moore’s legacy is carved into contradictions: the modernist who quoted Gothic cathedrals, the global celebrity who worked in a village, the abstractionist who insisted “all art is based on the human figure.” His sculptures now populate civic squares worldwide, yet their power lies in intimacy—the way a concave space invites touch, or a bronze patina recalls weathered skin.

When he died in 1986, his studio remained strewn with bleached bones and river-smoothed pebbles, the raw materials of a man who believed “stone has its own life, and you mustn’t violate it.”

Today, as contemporary artists grapple with ecology and embodiment, Moore’s work feels newly relevant. Not as flawless icons, but as weathered markers—like menhirs or standing stones—that ask us to measure our fragile flesh against the deep time of the land.

In 2025, Henry Moore would be celebrating his 127th birthday (born July 30, 1898).

10 of Henry Moore’s most significant works

1. Reclining Figure (1929, Leeds Art Gallery)

Why Significant? His first major public commission, blending Pre-Columbian influences with modernist abstraction, was a radical departure from traditional British sculpture.

2. Mother and Child (1932, private collections)

Why Significant? A tender yet primal exploration of familial bonds, carved directly in Hornton stone, showcasing his early “truth to material” philosophy.

3. Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure (1934, Tate Modern)

Why Significant? His first experiment with fragmentation, breaking the human form into abstract, interlocking shapes—a precursor to his later pierced sculptures.

4. Shelter Drawings (1940–42, Imperial War Museum)

Why Significant? Haunting sketches of Londoners huddled in Underground stations during the Blitz, capturing wartime resilience with raw, expressionist lines.

5. Madonna and Child (1943–44, St. Matthew’s Church, Northampton)

Why Significant? A rare religious commission, softening his abstraction into a universal maternal image, carved in muted brown Hornton stone.

6. Family Group (1948–49, Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Why Significant? His first large-scale bronze public sculpture, merging modernist simplicity with communal themes for postwar Britain.

7. Reclining Figure: Festival (1951, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art)

Why Significant? Created for the Festival of Britain, its hollowed-out torso and flowing lines became iconic, reflecting his fascination with landscape and anatomy.

8. King and Queen (1952–53, Glenkiln Sculpture Park, Scotland)

Why Significant? A mythic yet approachable pair, blending primitive power with regal stillness—one of his most universally recognised bronzes.

9. Nuclear Energy (1964–66, University of Chicago)

Why Significant? A chilling monument to the first controlled nuclear reaction, its mushroom-cloud silhouette merging science and sublime terror.

10. Large Two Forms (1966–69, Art Gallery of Ontario)

Why Significant? A late-career masterpiece, where two massive biomorphic shapes converse like ancient standing stones, distilling his life’s work into pure form.

Henry Moore’s top 10 auction results, showcasing the market’s recognition of his most coveted sculptures and drawings:

1. Reclining Figure: Festival (1951)

Price: £19.1 million ($24.8 million)

Auction House: Christie’s London (2012)

Details: A seminal bronze from his Festival of Britain series, exemplifying his signature pierced forms.

2. Reclining Figure: Draped (1952–53)

Price: £12.3 million ($18.1 million)

Auction House: Sotheby’s London (2014)

Details: A rare draped variation, merging fluid fabric-like textures with organic abstraction.

3. Working Model for Reclining Figure: Lincoln Centre (1963–65)

Price: £9.4 million ($12.4 million)

Auction House: Sotheby’s London (2016)

Details: A preparatory model for his iconic Lincoln Centre commission.

4. Reclining Figure (1956–57)

Price: £8.3 million ($10.9 million)

Auction House: Christie’s London (2012)

Details: A mid-career masterpiece with sweeping, landscape-inspired curves.

5. *Two-Piece Reclining Figure No. 3* (1961)

Price: £7.4 million ($9.7 million)

Auction House: Christie’s London (2016)

Details: A bold experiment in segmented forms, bridging figuration and abstraction.

6. Sheep Piece (1971–72, bronze)

Price: £6.9 million ($8.8 million)

Auction House: Sotheby’s London (2019)

Details: A late pastoral work, inspired by watching sheep in his Hertfordshire fields.

7. Reclining Mother and Child (1960–61)

Price: £5.8 million ($7.6 million)

Auction House: Christie’s London (2014)

Details: A tender yet monumental take on his lifelong maternal theme.

8. Standing Figure: Knife Edge (1961)

Price: £5.2 million ($6.8 million)

Auction House: Sotheby’s London (2018)

Details: A vertical counterpoint to his reclining figures, with razor-thin precision.

9. Maquette for Three-Piece Reclining Figure: Draped (1975)

Price: £4.7 million ($6.2 million)

Auction House: Christie’s London (2017)

Details: A small but potent study for one of his final draped figures.

10. Helmet Head No. 4 (1950, bronze)

Price: £4.3 million ($5.6 million)

Auction House: Sotheby’s London (2015)

Details: A haunting exploration of interior/exterior space, inspired by armour.

Market Insights:

Reclining figures dominate, reflecting their iconic status.

Large bronzes command premiums, but even maquettes (preparatory models) fetch millions.

Postwar works (1950s–60s) are most sought-after, blending maturity and innovation.