Tate’s new Picasso exhibition is not, we are told in the catalogue, “an exhibition that explores the relationship between Picasso and theatre”. It is a ‘gesture’ to “bring out new relationships [between his works] and audiences”. Thus, the exhibition is not about what Picasso was doing with his various paintings and sculpture but about the works’ afterlives when they have left the artist’s studio.

In the case of the central painting in the show, Picasso’s The Three Dancers, painted in 1925, he began it with a more classical aesthetic than it appears to us now. Leaving the painting unfinished, he then made a trip to Monte Carlo to visit the Ballet Russe with his ballerina wife, Olga. On his return to Paris, he reworked it to have its present, more frenzied appearance. If it started as an interpretation of the Three Graces, the figures became more frenzied maenads. What was Picasso up to in this large canvas? Despite the massive amount that has been written about him, he was remarkably silent on what his art meant to him. He left his audiences to their own interpretations as they so wished. Thus, it has been interpreted biographically; the response to the news of the death, in March 1925, of a Catalan friend, Ramod Pichot, or an expression of his growing disenchantment with his wife. Nothing conclusive has yet been settled on.

The Three Dancers was among the works Picasso kept, not letting his dealer, Paul Rosenberg, sell it. But come 1939, when Alfred H. Barr Jr., Director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, was putting together loans for his show Picasso: 40 Years of His Art, the painting left the artist’s studio, together with other paintings from Picasso’s personal collection. It crossed the Atlantic and began to take on other connotations. Today its life in America has been eclipsed by Guernica, but with the outbreak of World War II and the subsequent Nazi Occupation of France, The Three Dancers too moved from being an ‘exhibition loan’ to a ‘war loan’. Picasso was known to be living in Paris, and his paintings in America became symbols of his defiance in the face of the Occupation. MOMA ensured it was seen. Displaying it in their entrance, touring it and exhibiting it in a show of Large-Scale Modern Paintings in 1947. There, alongside paintings by Siqueiros, Matta, Lam, it took on other meanings for a new generation. It was returned to Picasso in 1958.

Despite its seven-foot stature (215.3 x 142.2 cms), The Three Dancers seems almost dwarfed alongside Fernand Léger’s Composition with Two Parrots, (1935-9), and Jackson Pollock’s Mural, (1943), in installation photos of Large-Scale Modern Paintings. Why did Picasso choose this format? We have no definite answer, not one at least from the ‘horse’s mouth’. That it was a statement piece – yes, yet it remains a format he did not choose often. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is 243. X 233.7 cms, and I think we know this was a breakthrough piece; choosing such a size was also a way to make his point. The Three Dancers is smaller but still large. It is what I would call full-length portrait size, giving its subject presence. I have not trawled through Picasso’s catalogue raisonné, Zervos, but from memory I can think of one Still Life from 1924, Mandolin and Guitar, which is 140.7 x 200.3 cm. Guernica is of course larger, 349.3 x 776.5 cm, as is Picasso’s mural War and Peace in Vallauris, 1000 x 500cm, and his The Fall of Icarus for UNESCO covers 90 m². These last three are surely best understood as architectural. I may have forgotten some, but Picasso did not paint many that are so large.

Picasso, of course, worked in the theatre, designing for the Ballet Russe and for Count Étienne de Beaumont’s Soirées de Paris. He was taught how to paint stage scenery by Vladimir Polunin. Stage scenery is vast, and there exists a photograph from 1917 taken by Harry B. Lachman that shows Picasso and scene painters sitting on the front cloth for the Ballet Russe’s production of Parade during the painting of this theatrical cloth, which would be the first thing the audience would see. The painters look tiny against the size of the painted cloth. But Picasso seems not to have taken up the gauntlet of size from these experiences. But their sizes make them arresting and eye-catching, which I am sure Picasso did have in mind. Did this not come from the theatre, or did it come from his early training in academic work, where a painting of size could still be seen, even if it was hung high up, if it was suitably large?

Picasso’s mind is also something to consider. If we think just of a simple drawing, any drawing by anyone. It starts in the mind, goes through the eyes, down the arm to the hand and into the pencil or brush. Sometimes the thinking goes on down on the page, or canvas. The results are feathery lines that must be worked on. But with Picasso, the entire drawing seems to have formed in his head before it travels down his arm to the page. This is captured to perfection, in 1949, in a series of photographs by Gjon Mili that capture Picasso drawing with light. Leaving his camera shutter open, he caught the trail of the tiny light Picasso used to draw centaurs, bulls, Greek profiles in the air. With no leeway for mistakes, Picasso knew exactly what the drawing would be before he even started.

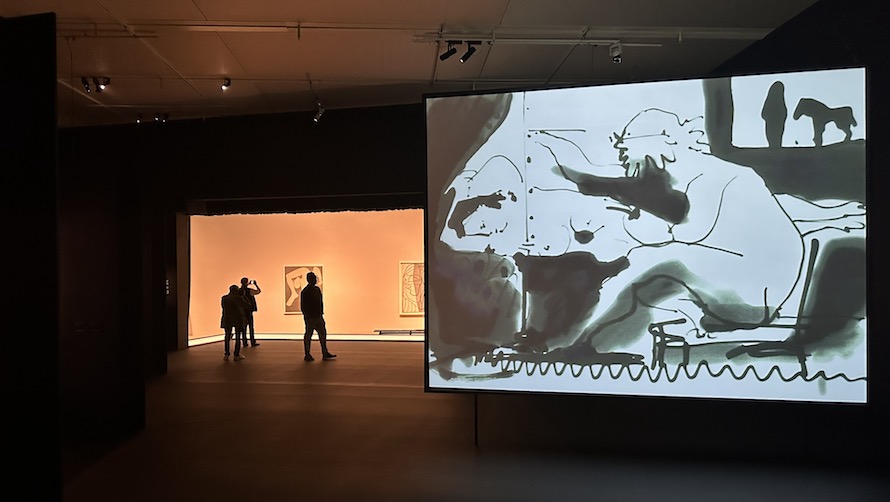

The exhibition includes a showing of The Mystery Picasso, directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot in 1956. It is a documentary of the creative process. By using thin paper and inks that penetrate through the paper, the audience sees the creation of a work without the artist’s hand to obscure the process. By filming the other side of the paper, the images just appear and build as Picasso adds them. They seem random, but one comes to realise he knows exactly what he is doing. He has thought it all through first. “What we see is a performance, for Picasso was a consummate performer. It has been suggested such performances where to keep the audience out of his studio, away from what work was really on his mind. A diversion to cover an enigma.”

This is a show of all of Tate’s holdings of Picasso, augmented by loans from the Musée National Picasso Paris and the Musée Picasso Antibes. It is not displayed chronologically, nor is the viewer tasked with reading long labels. It is an exhibition about what you, the exhibition audience, think. For me, I will continue to puzzle over what Picasso thought.

Theatre Picasso, Tate Modern, 17 September 2025 – 13 April 2026.