‘I only felt safe and comfortable in the studio with Israëls – they were wonderful afternoons, lazy, I believe – he drew a little portrait of me – crayon – I just sat very still – resting easily and he talked – talked … he shook me awake out of my sad dreaming – my indifference…’ It’s 1895. Jo is a young widow, burdened by an immense task, but her friendship with the painter Isaac Israëls makes her feel alive again. She confides it in her diary.

A little-known but highly influential figure: Jo van Gogh-Bonger (1862-1925), wife of Theo and sister-in-law of Vincent van Gogh, is the woman who dedicated her life to a single mission: promoting Vincent’s art.

2025 marks the centenary of Jo’s death, and the Van Gogh Museum is dedicating a very special small-scale exhibition to her: Captivated by Vincent. The Intimate Friendship of Jo van Gogh-Bonger and Isaac Israëls (until 25 January 2026), curated by Hans Luijten and Lisa Smit. Through paintings, drawings, sketches, diaries and letters, we discover Jo’s heartfelt friendship with the Dutch impressionist painter Isaac Israëls (1865-1934), and the many portraits he painted of her. We also find a new expression, ‘Vincenting’, coined by Israëls, who had borrowed several masterpieces by Van Gogh from Jo, including the Sunflowers, which appear in the background of many of his works. The exhibition is the culmination of years of research, taking us into the thoughts of Jo and Isaac, into their intimacy. The spirit of an age: it coincides with the launch of the digital edition of over one hundred unpublished letters that Israëls wrote to Jo, edited by Hans Luijten, senior researcher at the Van Gogh Museum and author of the biography Jo van Gogh-Bonger: The Woman Who Made Vincent Famous.

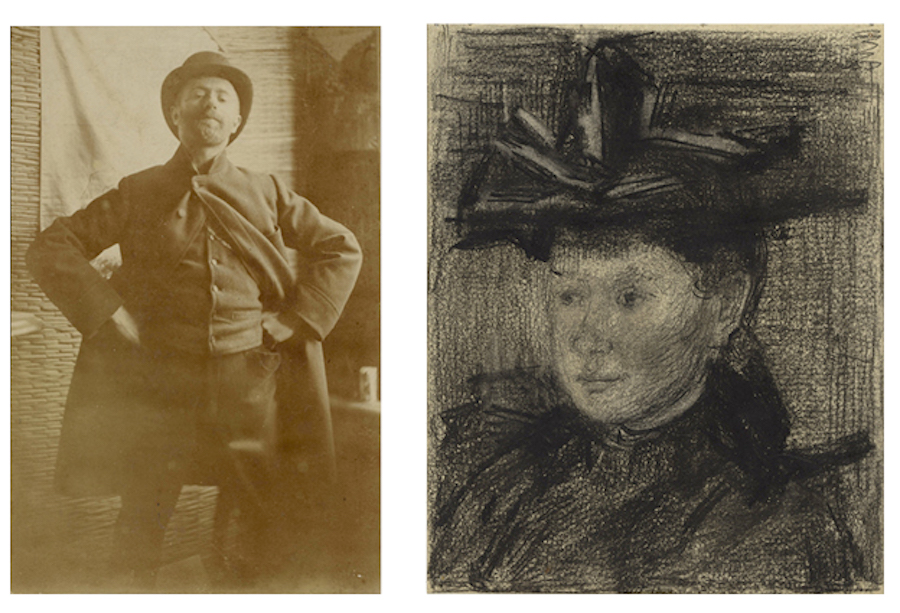

From the left: Isaac Israëls, ca. 1888 (Joseph Jessurun de Mesquita [attributed to], photograph), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; Isaac Israëls, Jo van Gogh-Bonger, 1895, chalk drawing, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

Jo’s mission is a monumental task

Jo married Theo in the spring of 1889 and moved to Paris. She experienced her marriage as ‘the most beautiful one can dream of’. But her dream would not last. At the end of July 1890, Vincent would commit suicide, shooting himself in the chest. Six months on, Theo, who had encouraged and supported his artist brother for over a decade, also passed away, leaving her with their baby, named Vincent after his uncle.

At 28, Jo suddenly found herself alone in a Paris apartment surrounded by a colossal burden. Hundreds of paintings, not just hung on the walls but stuffed under beds, hundreds of drawings by a virtually unknown artist, piles of letters, and a child whose first birthday fell just a week after his father’s death.

She returned to Holland and opened ‘Villa Helma’, a boarding house in Bussum, which was a lively cultural hub not far from Amsterdam. There she would begin to weave together a web of contacts, critics, painters, writers – anyone who could help her to gain recognition for Vincent’s life and work. Working tirelessly, she organised strategic sales exhibitions, and in 1905 she staged the largest ever retrospective of Vincent’s oeuvre, at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, with over 480 works on display. She immersed herself in reading Vincent’s letters to Theo, a truly emotionally demanding undertaking: ‘I literally live with Theo and Vincent in my thoughts’.

Jo felt like the heir to the mission initiated by Theo and carried it forward day by day with passion and tenacity. Her struggle was particularly significant in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a period heavily dominated by men. Her lines tell of a young woman, both progressive and conflicted. On one hand lay her motherly duties and the monumental task of ‘keeping all the treasures that Theo and Vincent had collected intact for the child’. On the other, was her highly independent spirit, her desire to be a woman – free to live and free to love. Sometimes pain and loneliness assailed her: ‘my grief is becoming master of my thoughts because I feel weak. The child with his head of golden curls is my only ray of light.

Isaac Israëls, Portrait of Vincent Willem van Gogh, 1894, oil on panel, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation). Photo © M. Guzzoni/Artlyst 2025.

Isaac and Jo, ‘playing with fire’

‘Israëls came to see me today. – At last, I have a portrait of the child now – I can’t help thinking about it all the time – it’s wonderful to have it. – The little blue eyes look so serious…’. The year is 1894.

Portrait of Vincent Willem van Gogh is a miniature painting on panel, exquisitely impressionist, 15 cm high, less than a hand’s breadth (here displayed in a glass case). This picture of the baby – ‘my angel’ – opened her heart. For some years, Jo and Isaac had an intimate friendship; they had many interests in common: art, literature, and theatre. Jo visited his studio, spending wonderful afternoons there. But in the portrait Isaac painted of her in those years (newly restored), her gaze speaks to us, magnetises us. It tells of a woman searching for something, perhaps for happiness she cannot find.

Isaac Israëls, Portrait of Jo van Gogh-Bonger, 1895-97, oil on panel, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation). Photo © M. Guzzoni/Artlyst 2025.

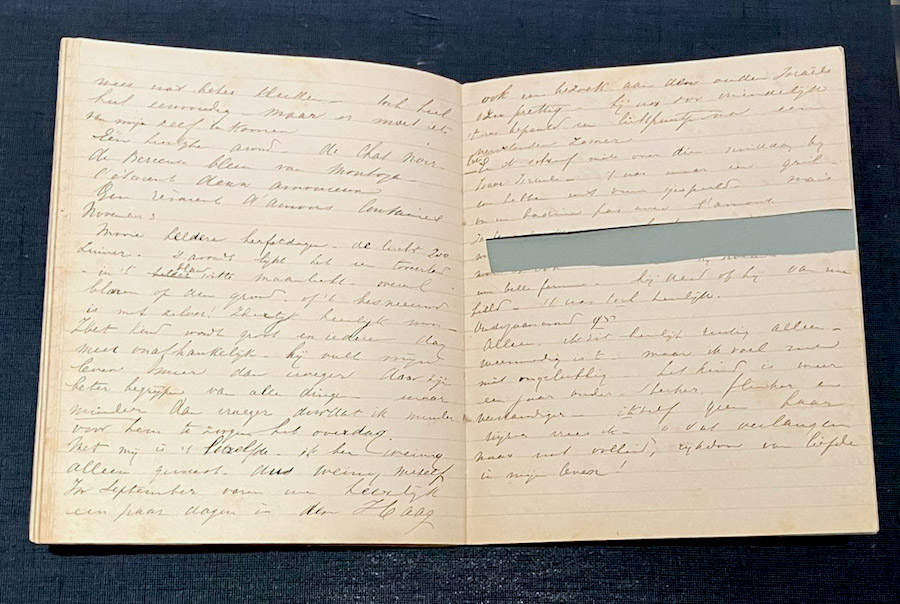

Isaac knew how to capture her thoughts and put them on canvas. From time to time she sent him bouquets of flowers, they exchanged books, short messages; just once, he signed himself ‘your boyfriend’, ‘I would come to see you, but you’re never on your own. The opposite to me’. Jo was torn, she knew that Isaac was not ‘a man for marriage…’ ‘it was just an impulse, we played with fire – but there’s no trifling with love […..]’. This page of her diary on display has a cut out, three lines not to be left to posterity.

Jo van Gogh-Bonger, Diary no. 4 (1892-1897), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation). Photo © M. Guzzoni/Artlyst 2025.

‘The highly inflammable, reddish-haired charmer that Israëls was, went through life as a libertine, and Jo was not impervious to his charm’, says Luijten. At a certain point, she decided to put an end to their ‘ambiguous’ relationship. Once Isaac commented: ‘you are the eternal slave to your duty or your sense of duty’, but in the end he agreed to break off. However, their friendship would not end.

‘I’m still busy Vincenting’

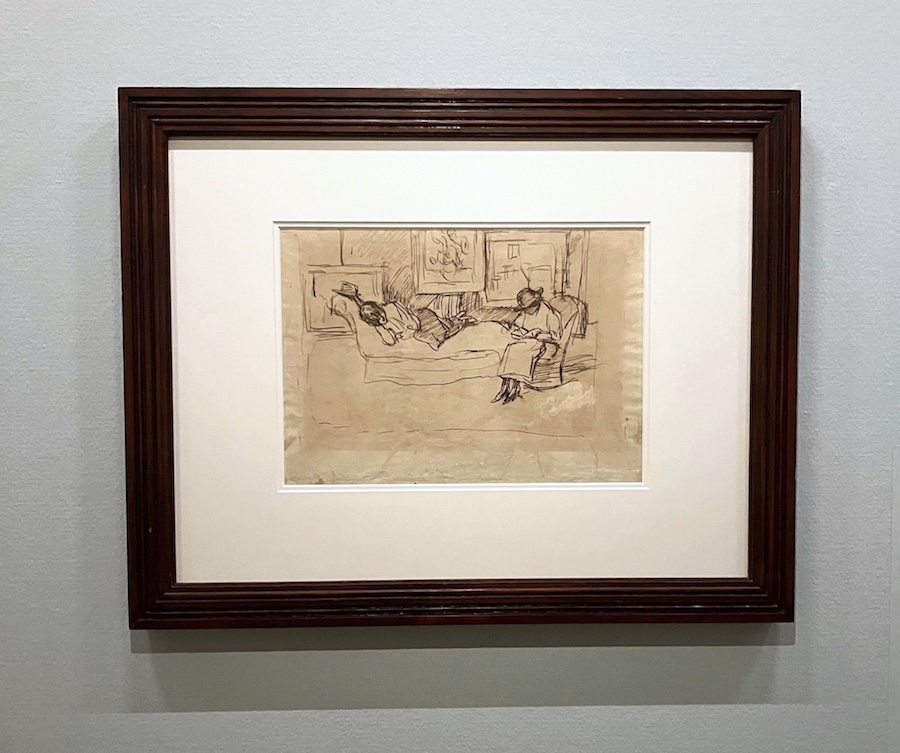

After years of hard work, in 1914, Jo succeeded in her goal: publishing, one at a time, the three volumes of Vincent’s letters to his brother Theo (Letters to His Brother). ‘But what a lucky devil, malgré tout, to have someone to whom he could say and write just anything, and that with no fear of being misunderstood. Not many people have that!’, Isaac wrote to Jo, thanking her for the first volume he received. Their friendship rekindled, so much so that Isaac asked to borrow some of Vincent’s paintings to study, including Sunflowers, The Bedroom and The Yellow House. We can see the three of them, displayed in the background of a large sketch, with the sunflowers at the centre.

Isaac Israëls, Woman reading to a Woman Lying on a Sofa, 1915-16, pen and ink on paper, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation). Photo © M. Guzzoni/Artlyst 2025.

Isaac was familiar with Vincent’s works, which he had admired in Paris and in Amsterdam, and especially at Villa Helma, where the walls were covered with them. Now he had the opportunity to have some paintings day and night, for months at a time. He incorporated them as backgrounds in at least sixteen canvases; twelve are on display (the whereabouts of the remaining five paintings are unknown). He was so fascinated that he gave a motto to his practice: ‘I’m still very busy Vincenting’, he wrote to Jo. One of these paintings is truly intriguing.

‘The big pot’, Woman Standing in Front of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers

Isaac Israëls, Woman Standing in Front of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, 1915-20, oil on canvas, Van Gogh Museum. Photo © M. Guzzoni/Artlyst 2025.

‘I think it’s very kind of you to send me these paintings, although – once they’re here, it’s very tedious to have to send them back again! It’s like adorning oneself with borrowed plumes. I want to hang the big pot, but I won’t do it…. But that pot? However, it’s one of the most important things you own, Isaac told Jo in December 1915.

A woman, seen almost from behind, stands admiring a painting of sunflowers. The painting is displayed on an easel. It is already framed, so it’s not a work in progress – the work of a painter who wants to show us what he’s doing. We don’t know who the woman is; she’s smoking a cigarette. We only see her blue blouse, one hand, her neck, and her head with her hair tied back. There is nothing else. We recognise Van Gogh’s Sunflowers.

In this painting, Israëls makes the Sunflowers a portrait of the act of looking, an ode to contemplation. The observer of the work becomes the work itself, is transformed into the work. We are enveloped in this aura of silence, of an interior calm that converts silence into emotion.

But if we pause for a moment, there’s something amiss about these sunflowers… and yet they are by Van Gogh, there’s no doubt about that. What’s amiss? The image. A careful comparison allows us to discover that Israëls, for unknown reasons, created a mirror version of Vincent’s Sunflowers. The mirror image of Vincent’s composition, in fact, matches Israëls’s painting almost perfectly, except the flower in the lower left. But that’s not all. To fit it all into his canvas, Isaac reduced its size by almost exactly half (perhaps with the help of a grid). Unfortunately, we have no comments in his letters, and not even Jo’s diary can help us.

Israëls was an ironic man, and here he made a subtle variation on the original and played with us, the viewers, offering a mirror image. The structure of the work is preserved, but an expert eye is disoriented. How many will notice it? The artist seems to wonder…

It was 1924 when Jo decided to part with the Sunflowers on a yellow background and sell the painting to the London National Gallery (a second version is preserved at the Van Gogh Museum), ‘a sacrifice for the sake of Vincent’s glory’, she wrote to the director of the museum. She was right. Homages to Vincent’s iconic painting were and still are numerous. Even some British artists in the 1930s attempted the theme, as the landmark exhibition Van Gogh and Britain (Tate Britain, 2019) well documented, with glowing bouquets of Sunflowers by Jacob Epstein (1933), by William Nicholson (1933) and others.

However, Woman Standing in Front of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers opens up broader reflections. More than a century later, it is part of a game of reverberations, a triangulation of absolute modernity, which has to do with the enjoyment of the work of art, and the experience of beauty. Once again, ‘the big pot’ teaches.

Top Photo: Isaac Israëls, Woman Standing in Front of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, 1915-20, oil on canvas, Van Gogh Museum. Photo © M. Guzzoni/Artlyst 2025.

Captivated by Vincent. The Intimate Friendship of Jo van Gogh-Bonger and Isaac Israëls Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam 12 September 2025 – 25 January 2026

* Further reading

Isaac Israëls’s letters to Jo van Gogh-Bonger and Jo’s Diaries, ed. by Hans Luijten, can be consulted at:

https://israelsletters.org

https://bongerdiaries.org