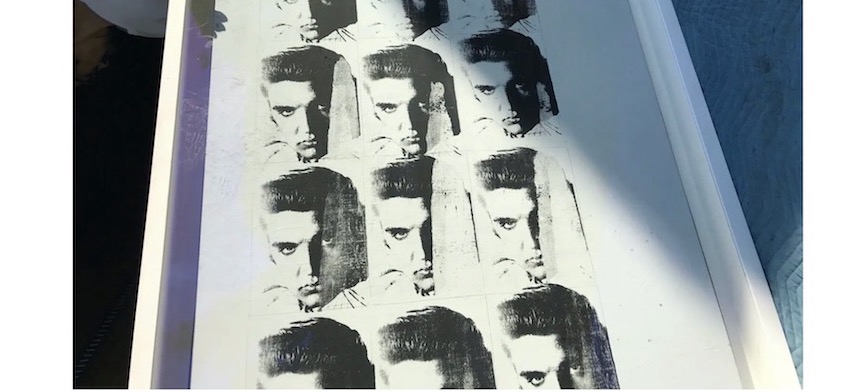

A New York judge has dismissed Ronald Perelman’s attempt to claim $400 million from insurers for paintings he said had been damaged in a 2018 fire at his East Hampton estate. The billionaire financier and collector argued that five works—two Warhols, two Ruschas, and a Cy Twombly—had been ruined by smoke, soot, and humidity. Justice Joel M. Cohen of the State Supreme Court found no evidence that the paintings suffered perceptible damage.

The decision, handed down on Friday, brought an end to a protracted five-year dispute that generated almost 2,000 court filings and drew in specialists to argue over fire science, smoke damage, and the stability of paint surfaces. Central to the case was Perelman’s claim that the fire had dulled Cy Twombly’s 1971 canvas of looping ovals. He told the court the picture had lost its “spark” and the clarity of its lines.

Insurers countered that the paintings were untouched. They accused Perelman of leveraging the fire as a cover for financial strain following steep declines in Revlon stock, the cosmetics empire he had taken over in 1985. The businessman has since sold around 70 works, raising nearly $1 billion to satisfy loans. Jonathan Rosenberg, representing Federal Insurance Company, argued that Perelman had shifted positions on the Twombly, offering it for sale when an expert found it undamaged, then pursuing an insurance claim when the sale failed.

Justice Cohen’s ruling was unambiguous: “I find that there was no visible damage to the five paintings. Nothing traceable to the fire.” While the court rejected the insurers’ claim that Perelman deliberately misled them, the judgment sided squarely against his bid for compensation.

The fire broke out in the attic of Perelman’s estate, The Creeks, a 72-acre waterfront property long associated with the collector’s public image. Some works were undeniably harmed—thirty pieces in total were acknowledged as damaged—but the five in dispute were not among them, according to the insurers. Lawyers for Perelman’s holding companies argued that the frames protecting the works were not airtight, and that humidity and smoke particles inevitably seeped in. Expert witnesses testified that the effects of such exposure may not be immediately visible but could alter paint layers over time.

The insurers dismissed these claims as speculative. They required policyholders to demonstrate a “perceptible, material, and negative change” to claim a payout. Anything less, they argued, would amount to an open-ended liability for subjective judgments on whether a painting had “lost its spark.”

Perelman’s testimony was brief but colourful. He compared Twombly’s lines to “a symphony orchestra,” insisting the canvas no longer carried the same vitality after the fire. Under cross-examination, however, he faced questions about attempts to sell other works from the house, including Brice Mardens that had survived the blaze. One of these, Letter About Rocks #2, was ultimately sold to hedge fund billionaire Kenneth Griffin for $30 million, after a visit arranged with dealer Larry Gagosian.

The insurers used these sales to argue that Perelman’s claims were inconsistent and motivated by liquidity pressures. They described the lawsuit as “a portrait of a contrived claim.” At the same time, Perelman’s lawyers countered that the insurers had shifted their position on which works they accepted as damaged, backing away from earlier acknowledgements once the most significant insured values came into play.

Perelman is no stranger to courtroom clashes. His litigious history includes disputes with Morgan Stanley, former spouses, and art world figures such as Gagosian. He has also cultivated a reputation as a philanthropist, donating $75 million towards the cultural complex at the World Trade Centre site and serving briefly as chair of Carnegie Hall before resigning in a power struggle.

The current case was notable for its unique testing of the boundaries of art insurance. The dispute extended beyond questions of market price, raising the more complex issue of whether a work can be considered damaged when no visible change is apparent. Perelman’s lawyers argued that his policies were designed around replacement value rather than auction benchmarks, ensuring he could keep his collection at a particular level. The insurers countered that this approach confused personal dissatisfaction with demonstrable loss.

Cohen’s judgment favoured tangible evidence over claims of lost vitality. For the court, the works by Warhol, Ruscha, and Twombly remain what they were: intact paintings, untouched by fire, soot, or water. Whether they still carry the same “oomph” for their owner is a matter, it seems, beyond insurance.

The decision leaves open the possibility of appeal, but for now draws a line under a dispute that exposed both the fragility of high-value collections and the legal complexities of insuring them. It also raises the broader question of how collectors, insurers, and courts approach artworks when the line between physical damage and subjective perception becomes blurred.

For Perelman, a collector with a history of turning litigation into theatre, the judgment is another chapter in a long-running saga. The Twomblys still hang, the Warhols and Ruschas remain in his possession, and the art world continues to watch as money, power, and perception collide in court.

Top Photo: Ronald Perelman Tribeca Film Festival by David Shankbone, Wikimedia Commons