The block of Great Jones Street between Bowery and Lafayette in Manhattan now carries a new name: Jean-Michel Basquiat Way. The Bowery has been home to many influential artists since the mid-20th century, with famous figures from the Abstract Expressionist, Pop Art, Beat Generation, and street art movements having lived and worked there.

The street sign, unveiled on October 21, marks the city’s recognition of the artist who emerged from downtown New York’s gritty, chaotic scene to achieve international renown. Members of the New York City Council joined Basquiat’s family, including his sister Lisane, for the ceremony. The signs stand outside the building where Basquiat lived and worked from 1983 until he died in 1988, a five-story loft he rented from Andy Warhol.

Basquiat died there at age 27, the victim of a heroin overdose. Today, the building bears a plaque commemorating the artist’s presence, and it has been leased by Angelina Jolie to house her fashion brand, Jolie Atelier, operating as a showroom and curatorial space.

Born in 1960 in Brooklyn to Haitian and Puerto Rican parents, Basquiat’s early life was shaped by a constant engagement with the visual world. He left home as a teenager, dropping out of school, and quickly made a name for himself on the streets of Lower Manhattan. Under the pseudonym SAMO, he sprayed cryptic slogans across walls, turning graffiti into a sharp, personal form of social commentary.

By the early 1980s, Basquiat had become deeply embedded in the downtown avant-garde. He moved in circles with Kenny Scharf, Keith Haring, and Arleen Schloss. His appearance in the 1980 Times Square Show put him on the map. Shortly after, he sold his first painting to Debbie Harry of Blondie and became the youngest artist to participate in Documenta, the prestigious German quinquennial.

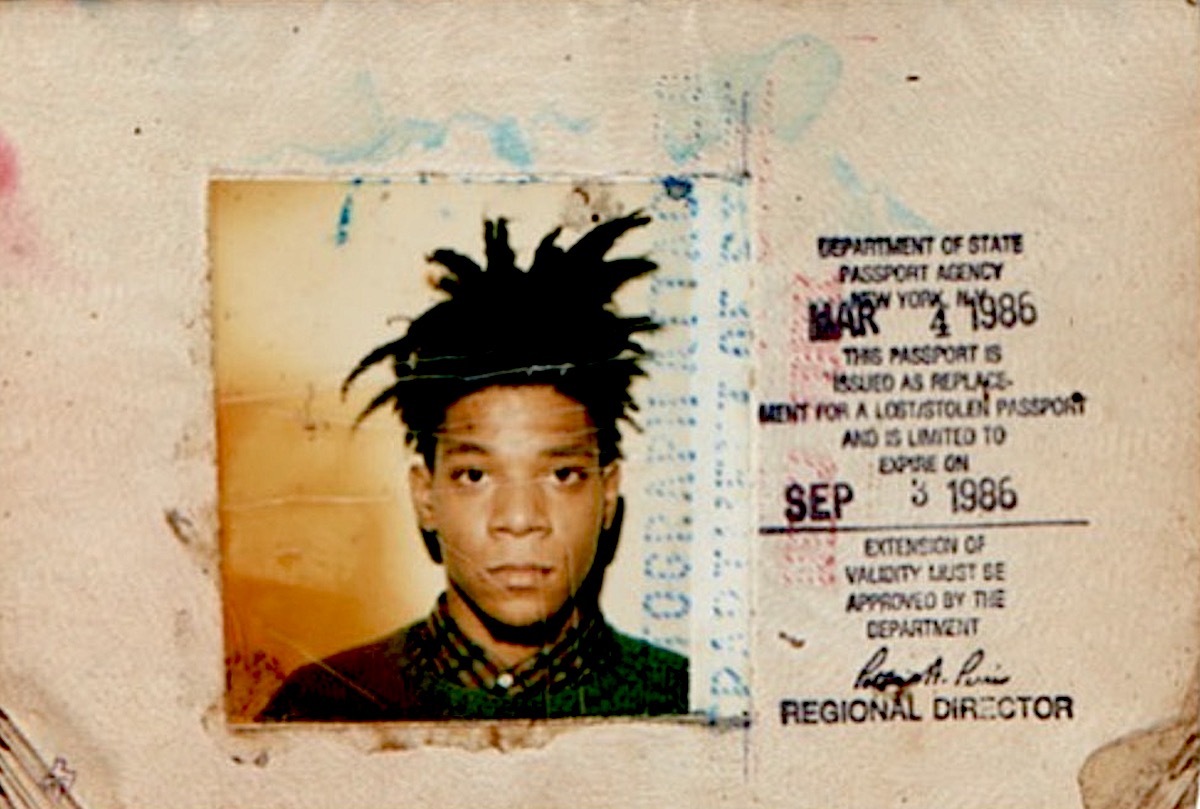

Success arrived fast. Basquiat travelled extensively, represented by dealers such as Larry Gagosian and Mary Boone. He was celebrated, scrutinised, and commodified in equal measure. The pressures of fame, coupled with a racially biased art world, contributed to his escalating drug use and unpredictable behaviour. The headlines often focused on the spectacle of his life rather than the substance of his work, a tension Basquiat seemed to confront in every mark he made.

This street naming in Manhattan is not Basquiat’s first urban tribute. In 2018, Paris inaugurated Place Jean-Michel Basquiat, a public square in the city’s 13th arrondissement, surrounded by streets honouring artists such as Paul Klee and Marcel Duchamp. In both cities, the gestures acknowledge his lasting impact on contemporary culture and the streets that shaped him.

Basquiat’s legacy is inseparable from the streets of New York. His name now marks a corner of the city that once served as a stage for his graffiti, a laboratory for his early experiments in text, imagery, and rhythm. It is a reminder that his art, like the city itself, was raw, urgent, and uncontainable.

Jean-Michel Basquiat was born in Brooklyn in 1960. From childhood, he moved through the city with his eyes open, absorbing every visual stimulus around him. Museums, books, films, sketches—these were his daily companions.

He copied drawings, studied anatomy diagrams, and collected images from comics and textbooks. These fragments of the world would later appear in his work, rearranged into symbols, marks, and coded language that only he could read thoroughly.

By his late teens, Basquiat had left school and home. He adopted the name SAMO, marking walls and subway stations with short, enigmatic phrases.

The city became his canvas. This was not play; it was a declaration. He demonstrated that graffiti could be sharp, critical, and visible to all, rather than being hidden in private collections. Soon, he moved from walls to canvases, doors, packaging, and clothing. Each surface carried the same urgency, the same insistence on immediacy and presence.

Basquiat’s work combines references from African, Aztec, European, and classical traditions with his own invented signs. History, identity, and social commentary collide across his surfaces. His first solo exhibition in 1982 confirmed what downtown New York already suspected: he was not only gifted but uncontainable. His work could bring the streets into the gallery, and the gallery into the streets, simultaneously.

Meeting Andy Warhol in 1983 shaped Basquiat’s public persona. They collaborated on paintings, but the partnership also exposed the pressures of the mainstream art world. As a young Black artist, Basquiat operated within a system that celebrated him while demanding he fit into narrow expectations. He accepted the attention but remained fiercely individual, and his paintings never surrendered their complexity.

Race is central in Basquiat’s work. His paintings address slavery, colonialism, and the African-American experience directly. They are urgent and political. Fame, however, complicated his life. By the mid-1980s, drug use intensified, and his temperament became more unpredictable. Dealers, curators, and friends sometimes struggled to keep up with him, but his work remained groundbreaking and edgy.

After Warhol died in 1987, Basquiat’s paintings took on a sharper, more urgent tone. His final canvases are full of apocalyptic imagery, grappling with loss and mortality. He worked feverishly, producing some of his most confident and mature work in the last year of his life. Basquiat died in 1988 at the age of 27.