Questions of attribution in Dürer’s work rarely reach certainty. One painting, quietly downgraded for decades at London’s National Gallery, has been thrust back into focus by a significant new publication. German scholar Christof Metzger argues in his catalogue raisonné that The Painter’s Father is not a later copy but an authentic work by Dürer, painted in 1497.

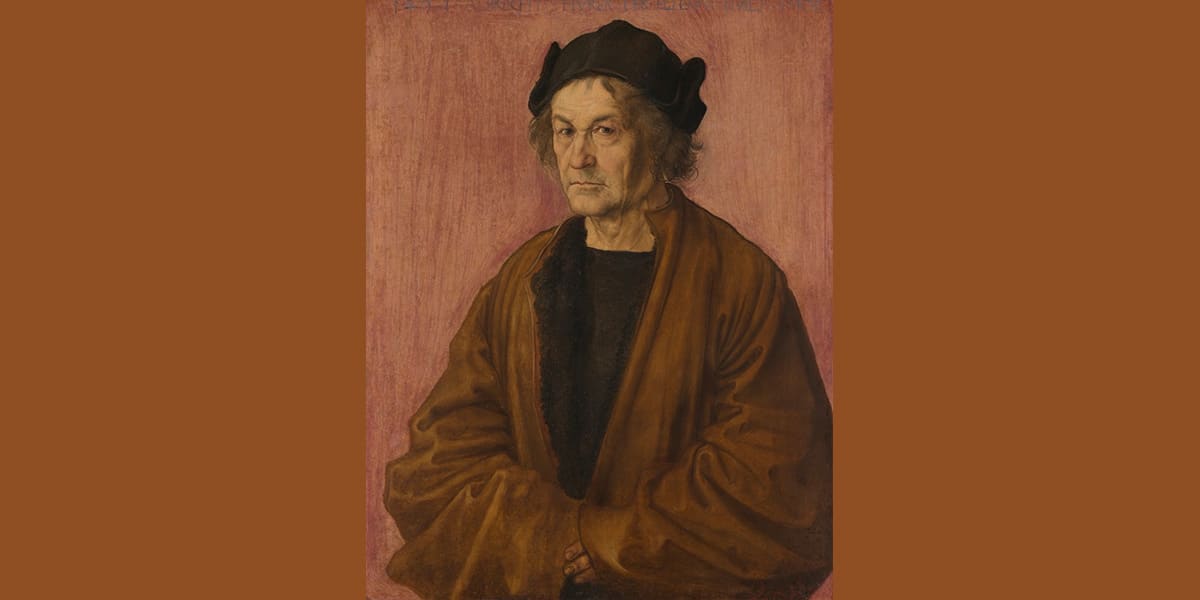

The inscription at the top of the panel identifies the sitter as seventy years old. Its wording is not disputed; the debate centres on whether Dürer himself applied it or someone later copied it from a now-lost original. The National Gallery maintains the latter, considering the painting a sixteenth-century copy produced decades after Dürer died in 1528.

The painting arrived in London with little recorded provenance. Yet a fragment of paper on the back of the panel, written in a hand resembling seventeenth-century script, suggests a more complex story. A similar label appears on the back of Dürer’s 1498 Self Portrait in the Prado, suggesting that the painting once belonged to Charles I. The label opens the possibility that the National Gallery’s portrait may have followed a similar journey.

A 1639 inventory of the royal collection includes the painting. Dürer’s father is described as wearing a black cap and a “dark yellow gown, his hands are hidden in the wide sleeves,” against a reddish background described as “all crack’t.” The National Gallery version matches that description in surprising detail. The technical details of the National Gallery’s The Painter’s Father have long invited scrutiny. The pink-red background is streaked, composed of a pigment that has faded unevenly over the centuries.

Drying cracks are more pronounced here than in works firmly attributed to Dürer, whose careful layering usually resulted in a smooth, even surface. The London panel seems to show paint laid in a single, thick layer, producing a texture unlike Dürer’s usual finishes. A comparison with the Prado Dürer Self Portrait highlights the contrast between the two paintings. The form is modelled with subtlety, facial features are precise, and the hair is carefully observed. By comparison, the National Gallery portrait appears flatter, less convincing, and sculpted, and is generally regarded as a copy after a lost original, probably dating from the late sixteenth century.

If this is the painting sent to Charles I from Nuremberg in 1636, the distinction between the original and the copy becomes more complicated. Dürer’s workshop copied works under his supervision. When the painting was presented to the king, authorship may have mattered less than the status it conveyed. This was a tangible tribute to one of Nuremberg’s most distinguished citizens, Albrecht the Elder

Upon its arrival in England, the painting passed through a succession of private collections before entering the National Gallery in 1904. Its surface, scarred and fading, has posed challenges for display. Although it was on view in the Sainsbury Wing for decades until the 2023 closure for refurbishment. The gallery is understood to be planning its return, reports TAN

Whether or not this painting is by Dürer, it continues to draw attention. It is popular with visitors who are invited to look beyond questions of authorship and view this superb portrait.