Dozens of film reels Andy Warhol shot in the 1960s have been developed and cleaned. They will premiere on 2 February at the Museum of Modern Art in a one-off screening titled Andy Warhol Exposed: The Newly Processed Films, which features more than an hour of unseen footage from material that had sat unprocessed for 60 years.

Shot by Warhol and his collaborators at the height of the Factory era, the films include Screen Tests, early experiments, candid documentation of Pop Art culture, and substantial amounts of explicit material that complicate long-held assumptions about Warhol’s work and persona.

In 2015, Katie Trainor, who manages MoMA’s film collections, was visiting the Pennsylvania facility where the museum stores most of Warhol’s film archive, which he began collecting in 1987. While examining the collection with Greg Pierce, then director of film and video, they noticed a box marked simply “raw stock”. The label had discouraged curiosity for years. Unused film from decades ago rarely promises a revelation, even when Warhol is involved.

A closer look changed that assumption. Inside were 45 rolls of 16mm film, each capable of holding around 4 minutes of footage. The reels showed signs of exposure. Some were even labelled. One read “Jerry & Girl”, likely pointing to Warhol assistant Gerard Malanga. Another bore the date 3 March 1966 and referenced a car ride to Ann Arbour, the journey Warhol took with the Velvet Underground for a now-legendary performance at the University of Michigan.

The find raised another question. Why had these rolls never been processed? No clear answer exists. The chaos of The Factory offers one explanation. Warhol filmed constantly and obsessively. Processing may not have kept pace. There was also the possibility that the images had faded entirely. Even so, Trainor and Pierce suspected there was something worth salvaging.

In spring 2024, the reels were sent to ‘Colorlab’, a specialist film laboratory outside Washington D.C. Thomas Aschenbach, the owner, has extensive experience dealing with ageing film stock and felt cautiously optimistic. Out of eighty-six rolls submitted, more than half proved unusable, either blank or ruined by exposure. Thirty-eight, however, survived with surprising clarity.

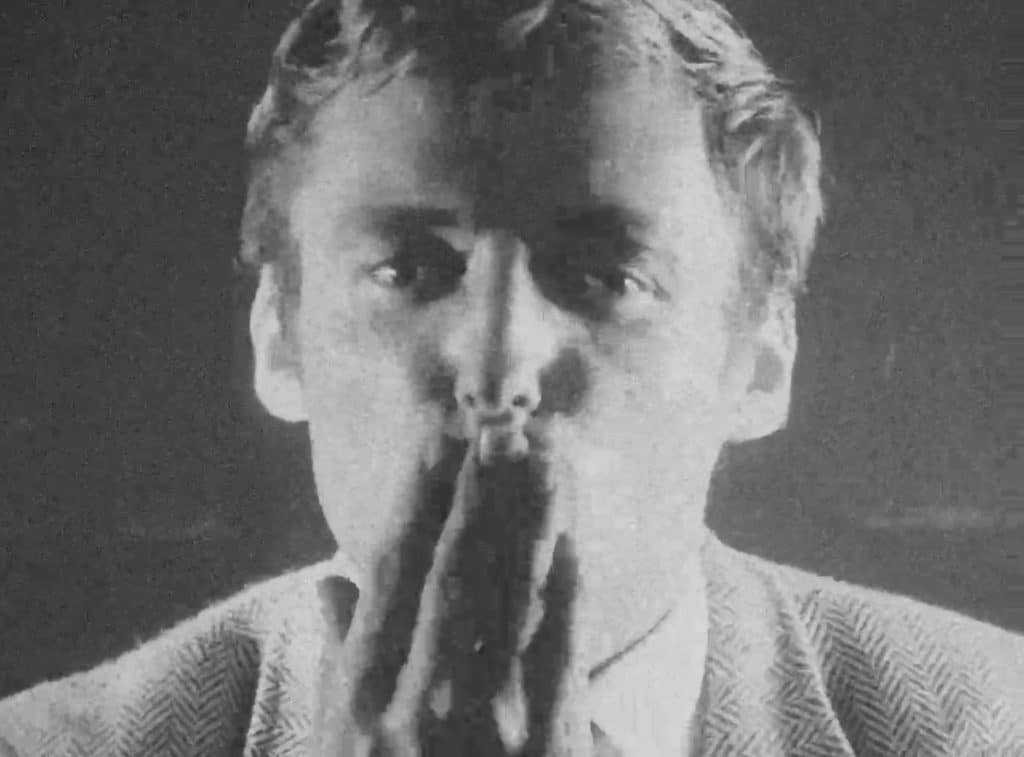

The actor Dennis Hopper in one of the Screen Tests.CreditCredit…Via The Museum Of Modern Art And The Andy Warhol Museum

What emerged was something more intimate and revealing. Eight new Screen Tests expand Warhol’s famous series of filmed portraits, which already numbers more than 400. Among them are familiar faces, including Dennis Hopper and Jane Holzer, alongside Naomi Levine, an early Warhol supporter who had been oddly absent from the Screen Tests until now. Other subjects remain unidentified.

The footage, unseen by the artist, offers insights into Warhol’s daily routine. A January 1964 reel captures a Frank Stella exhibition PV at the highly regarded Leo Castelli Gallery. Warhol was eager to break into this world. A March 1966 film documents a Factory party heaving with energy.

There are also fragments from known films. Nearly four additional minutes from Sleep show John Giorno, naked and unconscious, extending one of Warhol’s most durational works. Reels connected to the couch reveal further scenes of excess and intimacy unfolding on the Factory sofa, already infamous in Warhol mythology.

Around a quarter of the newly developed material is overtly sexual. Masturbation, oral sex and group encounters surface in grainy frames. The footage belongs firmly to the sexual politics of the 1960s, a period in which Warhol was quietly testing to the limits mainstream culture, which preferred not to acknowledge. Although his 1969 Blue Movie became the first explicit film to receive a full theatrical release, the years of the Factory are often remembered as strangely restrained by comparison.

Looking at the bigger picture, the films reveal an artist driven to record, placing his faith in the camera rather than recollection, and leaving behind a body of work that can still catch us off guard. That Warhol never saw these images feels strangely fitting. The material continues to emerge on its own wavelength, long after the artist has passed.

Seen together, for the first time, these newly released film segments sharpen Warhol’s legacy. They reveal an artist who filmed compulsively, trusted the camera more than memory, and Warhol’s record is still capable of surprising us.

The screening at MoMA offers a rare chance to watch history develop in real time, sixty years late, but undiminished in force.

Andy Warhol Exposed: Newly Processed Films From the 1960s, 2 February, 6.30 pm Museum of Modern Art, New York