In the hugely competitive world of art fairs, timing, as we know, is everything, but the location is equally important. Miart, Milan’s international modern and contemporary art fair, has ticked both boxes and takes place in April, just before the huge Milan Design Trade Fair (the largest trade fair of its kind in the world), and the Venice Biennale, a short train ride (or private jet) away, meaning the international VIP collectors are stopping off on their way to Venice. Inevitably, there is a little crossover with many sales made in Miart of artists whose work is also featured in the “no business” Venice Biennale. First Floor Gallery based in Harare, for example, sold several silicone weavings by Troy Makaza for up to €19,000 (£16,000), who is in Zimbabwe’s pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

It’s not really trying to compete with the commercial fairs like Art Basel or Frieze and is happy with its position as a medium-sized fair, but for me, it had a lot of appeal in terms of actual work and galleries. And, for all the reasons mentioned, it is an exciting time to visit Milan, with so many external projects running across what is one of the greatest Art Cities in the world.

This year, there were 169 galleries from 28 countries, showing at least a thousand works, many of which were from the UK. Then, of course, there are the most important Italian galleries, from the small experimentals to the blue chips.

For me, art fairs are not only a window into the art world, but also an opportunity to see museum quality works that may never see the light of day again.

Here, I focus on six of my favourite works at the fair:

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Uomo con zainetto (man with a backpack), 2018 was on show at Artemisia Fine Art and worked so well in this space, reflecting the trot-buy-trot-buy collectors and fair visitors rushing through a corridor. Pistoletto, who is now 90 and still working, is considered one of the leading exponents of the Italian art movement, Arte Povera, and his Mirror Paintings, like this one, are the foundation of his practice with a few choice ones on sale at the fair, from some of his earlier works to this later one.

Since the early 1960s, he has been using stainless steel polished to a mirror finish and screen-printed photographic images on top, with the mirrors reflecting the surroundings, such as the art fair visitors in this case, designed to open up a dialogue between the viewer and the image in front of them, in effect, giving the art fair visitors a central role in the artwork, quite literally becoming part of it, as his mirrored image start interacting with the printed motif.

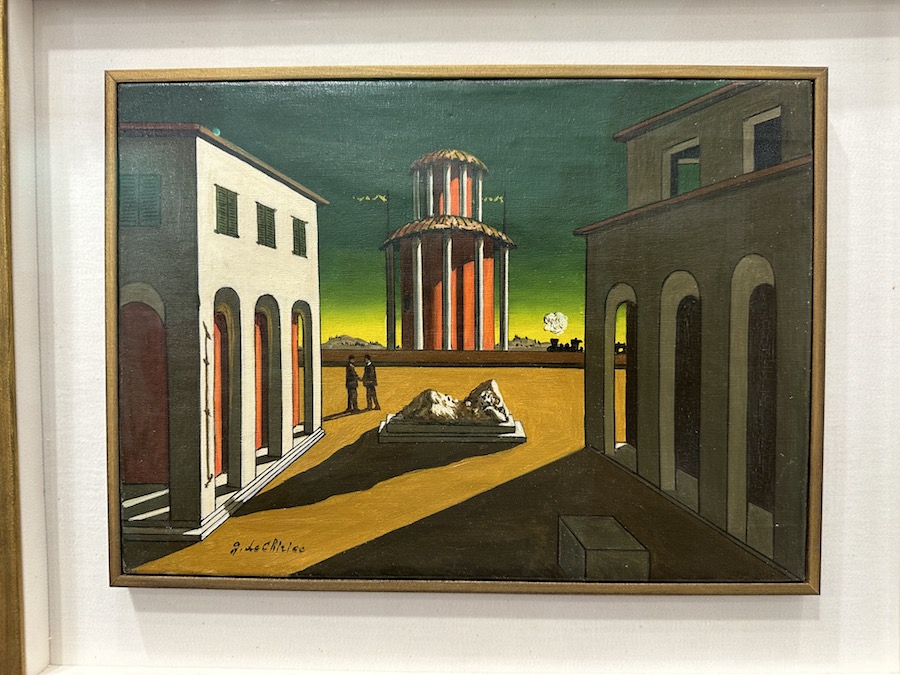

Tornabuoni Arte, a gallery that specialises in Post-War Italian Art, is showing a very nice selection of Giorgio de Chirico, including Piazza d’Italia, from 1958.

Metaphysical painting was developed by de Chirico and Carlo Carrà, in around 1911, and empty squares, like The Piazza d’Italia, were the most frequent subject and repeated theme in de Chirico’s oeuvre – and were a crucial inspiration for the Surrealist movement. Then, long after he first created them, the “metaphysical works” like this one, became highly sought-after by collectors, prompting him to create duplicates in order to keep up with demand.

In a business where authenticity is a crucial selling point, de Chirico became a self-forger from around 1937. An act that confused (and confuses) collectors and galleries by churning out copies of his own early twentieth century works for decades (exact dates are disputed) and calling these copies “verifalsi”, or “true fakes.” The copies (I think “replicas” is preferred by those investing in his work), are so similar that only experts can tell the difference between the earlier and later works. De Chirico didn’t see any problem with this, saying “that the idea is important, and the idea is what the artist owns,” an artist decades ahead of his time.

Apart from the de Chirico beauty, Tornabuoni Arte had a collection on display worthy of any museum collection.

A popular booth was Galleria Raffaella Cortese, who were showing a solo selection of Francesco Arena, a young artist from Brindisi.

His work, Altalena, is a bronze swing edition (of 3), on which is engraved: “All the present days are similar to each other” in one direction, and “each past day is different in its own way” in the opposite direction. Nicely polished from art fair visitor’s bottoms!

It was great fun watching the besuited and bejewelled Milanese who probably haven’t been on a swing for several decades, queuing up to have some silly fun, albeit on a swing priced at €35,000 (about £30,000), of which all three editions (and an artist proof), sold out.

One of my favourite spaces was Galleria Antonio Verolino from Modena, a gallery that specialises in tapestries. They were showing several beautiful works, including some by the influential artist Enzo Cucchi, an Italian painter and a central figure in the Transavanguardia movement of the 1980s Italian Neo-Expressionists, whose work was once described in the New York Times as an: “artist who waves his paintbrush like a magician’s wand.” Cucchi works in many different mediums, and the tapestry on display at the fair is a recent (2023) untitled work which incorporates a mix of ancient and modern mystical symbols. But in the same gallery, Sonia Delaunay’s hand-woven tapestry got my vote as the most desirable piece in the art fair. Delaunay, a pioneering artist in the fields of abstraction and applied arts, created “Monumental II” in 1975 and it is a significant work in the legacy of the artist, part of a series of works that explore the relationship between colour, form, and movement, ideas that took shape in the late 1960s, when she began to work in a medium loaded with tradition: tapestry. The one on show at the fair was a stand-out of classic Delaunay of bold, dynamic shapes and vibrant colours arranged in rhythmic patterns creating a sense of movement and energy. I want.

The well-established Galerie Lelong & Co, had some fine works on display, including four rare Robert Rauschenberg photos, giving new buyers an entrée into collecting an artist who’s prices are way beyond the reach of most. These all sold out on the first day.

In the same gallery, one of the biggest deals (that we know about) was a lovely David Hockney folding screen, Caribbean Tea Time, from 1987 which went within minutes of the fair opening for €580,000 (£500,300), from an edition of 36. Whoever bought it, got a museum quality piece, as the Tate has one in its collection (but I’ve never seen it), as does the Metropolitan Museum of Art. One of the same editions sold at Christies last year for $378,000 (£305,600).

It really is a gorgeous and unusual Hockney, a large-scale lithograph partitioned into four panels of a folding screen in stunning fauvist-like colours and floating shapes that playfully reference his previous works and remind us of Hockney’s forays into set design.

Then of course, in a city that you associate with the artist, Lucio Fontana’s work could be found at various galleries.

Fontana moved to Milan as a child (but was born in Argentina) and studied at Brera Academy. One of his works displayed at the fair was Concetto Spaziale, Attesta (Spatial Concept, Waiting) from 1963-64, a lovely green Fontana at Cortesi Gallery.

Earlier that day, we’d been on a Fontana walking tour organised by the hotel Principe Savoia, visiting the art supply shop where he got his materials and walking through the Brera Academy, where he studied in the late 1920s under the symbolist sculptor Adolfo Wildt. After working in Argentina with his father (also an artist), he returned to Italy in 1948 and exhibited his first Ambiente spaziale (‘Spatial environment’) at the Galleria del Naviglio in Milan. Fontana was the first known artist to slash his canvases – which he said symbolises an utter rejection of all art theory.

One of the nicest touches of the fair is having the “emerging” galleries in the initial section rather than tucked away in some corner, as you see at most fairs. This is a nice democratising element and means these galleries don’t get overlooked, as collectors scrambling to buy another Fontana must walk through the emerging artists.

All in all, Miart is a nice size fair, with some great galleries and fantastic work, and easy enough to do in a day, and then spend time seeing the numerous events around the city and then, of course, pop on a train down to Venice for the Biennale!

Words and Photos James Payne ©Artlyst 2024

MIART 2024 No Time No Place took place 12-14 April 2024

Visit Here