Sotheby’s will stage one of its most ambitious autumn seasons in living memory, as two of the most prominent collecting families of the past century—Chicago’s Jay and Cindy Pritzker and New York’s Leonard Lauder—send major works to auction. Together, their consignments mark a decisive moment for the house, which is attempting to steady itself after a turbulent few years under billionaire owner Patrick Drahi.

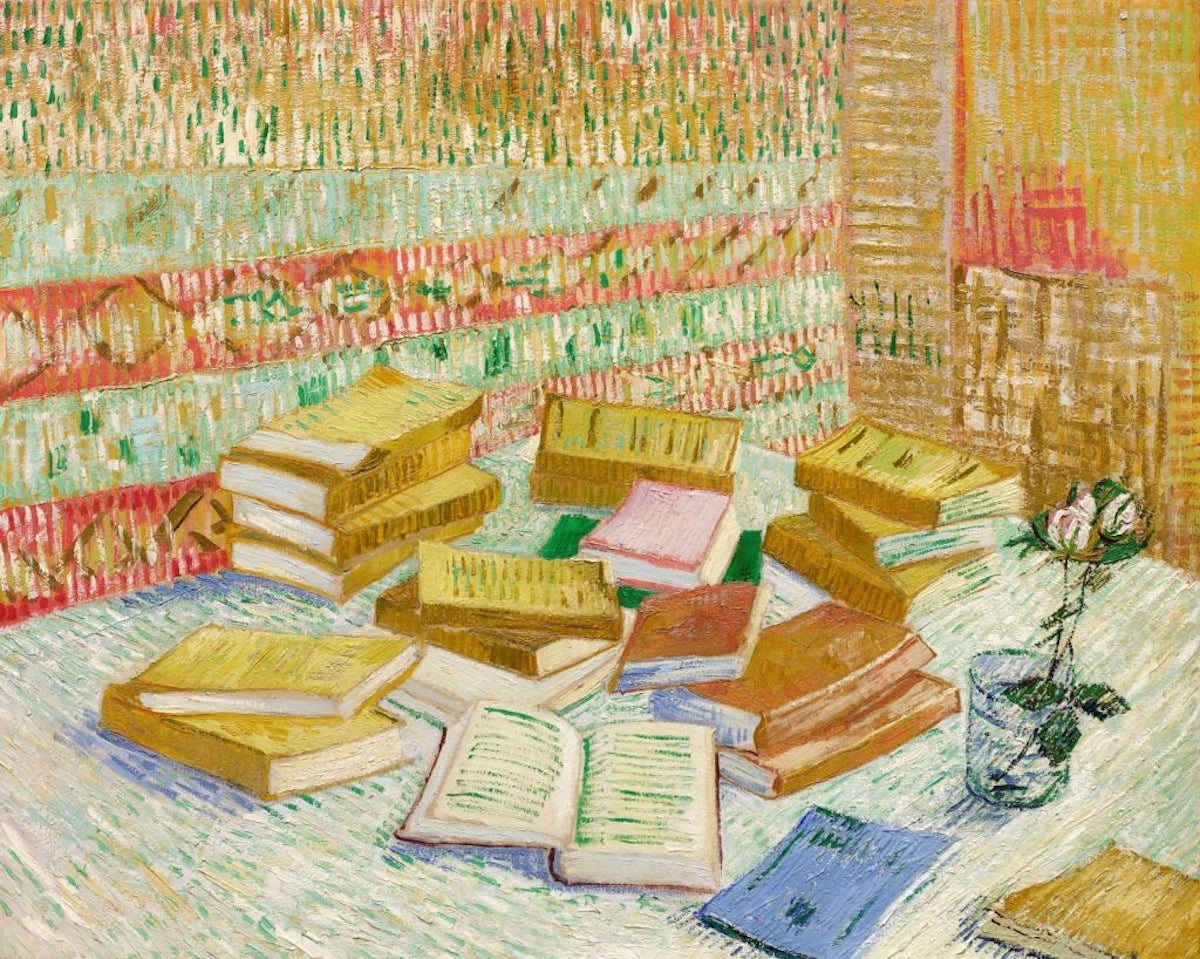

The first salvo comes with the Pritzker Collection, a group of Impressionist and Modern masterworks expected to fetch up to $120 million in Sotheby’s new Madison Avenue headquarters this November. Leading the sale is Vincent van Gogh’s Romans Parisiens (Les Livres jaunes), painted in 1887, a luminous still life that carries an estimate of $40 million. The canvas depicts a stack of yellow-backed paperbacks—Charpentier’s inexpensive “Romans Parisiens”—arranged with a quiet reverence that reflects both Van Gogh’s love of books and his Parisian milieu. The painting was last sold at Christie’s in 1988 for $12.2 million, and has since travelled through the world’s leading museums, from the Musée d’Orsay to the Royal Academy. Sotheby’s calls it “the finest Van Gogh still life to reach the market in decades.”

The Van Gogh is joined by other star lots: Henri Matisse’s triptych Léda et le cygne (1944–46), commissioned for a Paris home and famously admired by Picasso, carries a $7–10 million estimate; Paul Gauguin’s La Maison de Pen du, gardeuse de vache (1889) is valued between $6 and $8 million; while Max Beckmann’s brooding Der Wels (Catfish) (1929), a metaphor for life’s “terrible vitality,” is pegged at $5–7 million. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Hallesches Tor, Berlin (1913) will also appear, with a $3–5 million estimate.

Additional highlights include Joan Miró’s bronze La Mère Ubu (1975), based on Alfred Jarry’s anarchic play Ubu Roi, expected to fetch up to $6 million, alongside a Camille Pissarro river landscape priced at $1.8 million. A supporting cast of works by Braque, Botero, Calder, and Le Corbusier will anchor day sales. At the same time, the Pritzkers’ wide-ranging taste will spill into other categories, including manuscripts and Chinese works of art.

The sale marks a symbolic moment: the Pritzkers’ name has long been attached to Chicago’s cultural fabric, from the Art Institute to Millennium Park, not to mention the creation of the Pritzker Prize, architecture’s highest honour. Jay Pritzker, who founded Hyatt Hotels and built an empire across airlines and ticketing companies, died in 1999; Cindy, who championed public libraries and civic projects, died this March. The Van Gogh, with its bookish subject, seems a fitting tribute to her legacy.

This November sale will also serve as a debut for Sotheby’s renovated home in the Marcel Breuer-designed building that once housed the Whitney Museum. The house paid around $100 million for the Brutalist landmark in 2023, and enlisted Herzog & de Meuron—architects who have themselves won the Pritzker Prize—to refit the galleries for its marquee auctions.

Yet the Pritzker consignment is only the opening act. The season’s true leviathan is the Leonard Lauder Collection, a $400 million tranche announced just weeks after Lauder’s death at the age of 92. Long associated with the Whitney Museum—where he served as trustee and later chairman emeritus—Lauder was celebrated for his discerning acquisitions of Cubist works, many of which he donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2013. The group now headed to the auction reflects another side of his holdings.

At the centre is Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer (1914–16), a full-length portrait poised to become the most expensive lot of the season. The painting, once part of the Viennese artist’s circle of wealthy patrons, is expected to achieve more than $150 million, easily eclipsing Klimt’s standing record of $108.4 million set at Sotheby’s London in 2023 for Dame mit Fächer (Lady with a Fan).

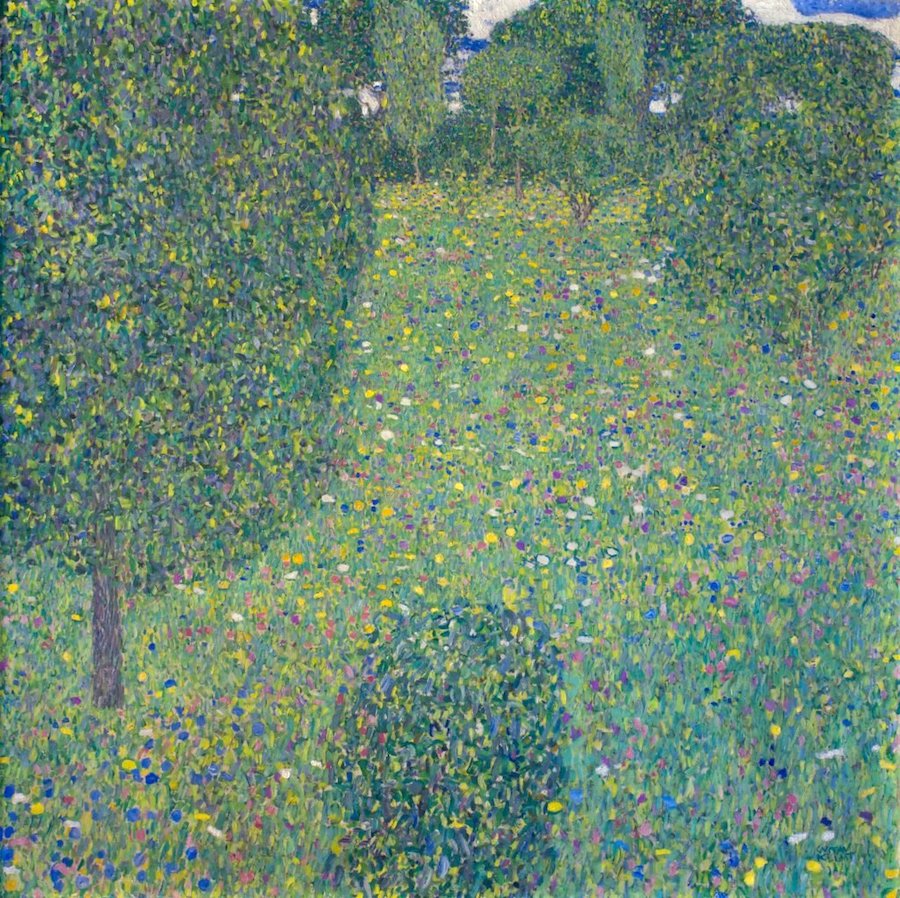

The Lederer portrait will be joined by two Klimt landscapes: a meadow from 1906 estimated at $80–100 million, and a forest scene from 1917 tagged at $70–90 million. Together, they underscore Klimt’s dual ability to capture both opulent society portraits and meditative natural vistas.

Lauder’s consignment also features six bronzes by Matisse worth $30 million collectively, an Edvard Munch painting with a $20 million estimate, and an Agnes Martin canvas valued north of $10 million. In total, 55 works will be dispersed across Sotheby’s November evening and day sales.

The announcement comes at a precarious time for Sotheby’s. The auctioneer, controlled since 2019 by Drahi, has faced mounting criticism over job cuts and strategic missteps. A failed sale of a $70 million Giacometti sculpture earlier this year, and a New Yorker profile painting Drahi as an erratic leader, have sharpened doubts. In August, the Guardian reported losses of $248 million. Against this backdrop, securing the Lauder collection is a coup—and one that the company insists will “make history.”

The scale of these consignments also reflects the continued polarisation of the market. As mid-range sales falter, the top end remains fiercely competitive, with estates and billionaire collections providing the most secure inflow of works. The Van Gogh, Klimts, and Matisse bronzes represent precisely the sort of trophies capable of igniting bidding wars across continents.

For Sotheby’s, the stakes are unusually high. The house has not only poured money into its new Breuer headquarters but also ceded part ownership to ADQ, an Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund, in a billion-dollar deal last year. With November’s sales, Drahi’s team will hope to show that the old model—prestige consignments, glittering evening auctions, and the gravitational pull of masterpiece lots—still holds power in an uncertain art economy.

Whether it is Van Gogh’s yellow paperbacks, Klimt’s shimmering portrait, or Beckmann’s monstrous catfish, these works are freighted with more than just art-historical weight. They represent confidence, legacy, and a market constantly recalibrating itself. The November sales will test not only Sotheby’s balance sheet but the broader resilience of the art trade at its highest level.

Top Photo: Vincent van Gogh, Romans Parisiens (Les Livres jaunes) (1887). Courtesy Sotheby’s.