Christie’s has set a new auction benchmark for Artemisia Gentileschi today, with her early self-portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria selling for roughly $5.69 million at the house’s Rockefeller Centre headquarters. The work, part of Christie’s January Old Master sale, more than doubled its pre-sale estimate of $2.5–$3.5 million.

The record eclipses Gentileschi’s previous auction high, €4.7 million ($5.25 million) for Lucrèce at Artcurial, Paris, in 2019. Adjusted for inflation, that earlier result would equal around $6.6 million, placing today’s sale just below that mark.

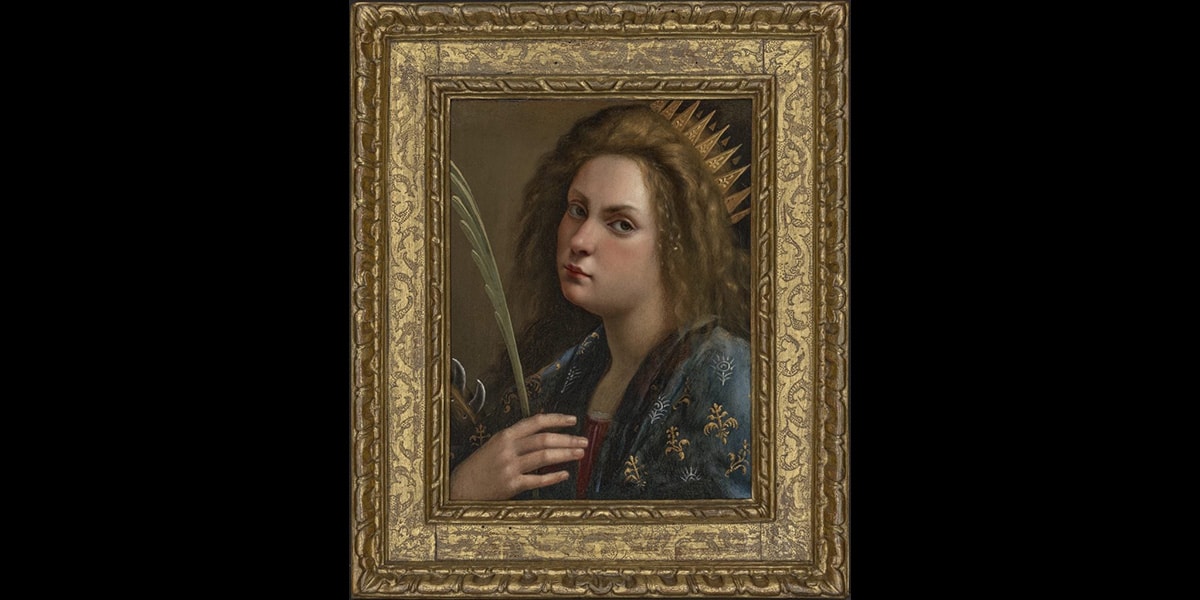

Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria is one of only five known self-portraits by the artist, three of which are held in museum collections. Believed to date from her Florence period, around 1613–1620, it was likely painted when she was not yet 20. The painting had been on loan to Oslo’s Nasjonalmuseet since 2022 and is slated for inclusion in the 2028 exhibition Artemisia Gentileschi: The Triumph of Painting at the Nivaagaard Collection in Denmark.

The auction record for the lot comes as the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., unveiled its acquisition of Gentileschi’s Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy (c. 1625). The painting captures the saint in a striking moment of spiritual intensity, evoking the lost 1606 Caravaggio Magdalene.

Gentileschi’s standing in both the market and scholarship has risen sharply in recent years, reflecting a broader push to re-evaluate women artists who have long been overlooked. Today’s record sale, alongside the NGA acquisition, highlights her lasting resonance, with collectors and institutions increasingly recognising her as a pivotal figure in 17th-century Italian painting.

Artemisia was born in Rome in 1593 in the orbit of Caravaggio. She would come to occupy an important place in Baroque painting due to her gender, as very few women were encouraged to become professional painters at the time. Trained in her father Orazio Gentileschi’s studio, she absorbed the dramatic chiaroscuro and psychological intensity of the Roman avant-garde early, developing a painterly confidence that was striking for an artist still in her teens.

Her early career was violently shaped by the rape she suffered in 1611 at the hands of Agostino Tassi and the public trial that followed, during which she was subjected to torture to verify her testimony. The episode has often threatened to eclipse her work. Still, it is impossible to separate her artistic trajectory from the clarity and force that followed. Paintings such as Judith Slaying Holofernes are not acts of confession but statements of control: women rendered with physical weight, resolve, and agency, painted with an authority few of her male contemporaries matched.

After leaving Rome, Gentileschi built an international career with unusual independence. She worked in Florence under Medici patronage, becoming the first woman admitted to the Accademia del Disegno, and later moved between Venice, Naples, and London. Her subjects, biblical heroines, martyrs, and mythological figures, are consistently framed from the inside out. These women think, decide, and act; they are not posed for spectacle.

By the time of her death in Naples around 1656, Gentileschi had established herself as a formidable professional artist, negotiating commissions, running a workshop, and signing her name with confidence.