I begin this month with two exhibitions that touch on religion in the context of exploring identity and end with a series of book-based installations that probe aspects of the nature of Christianity.

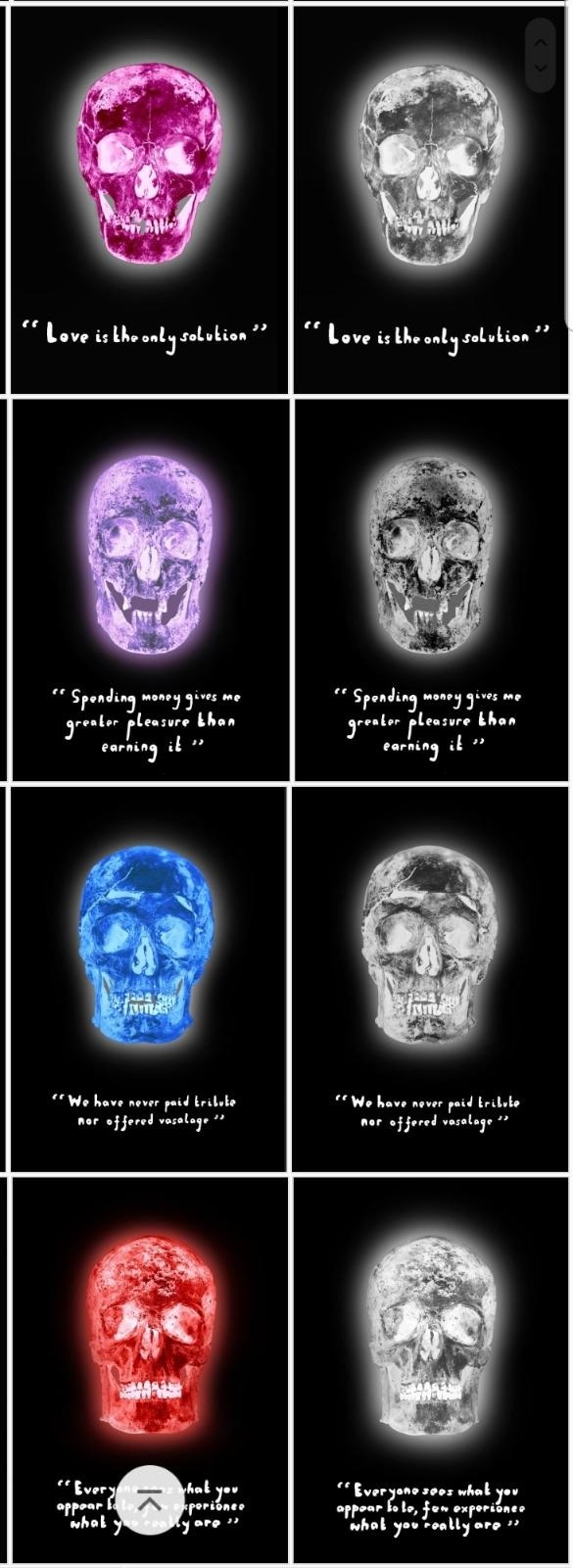

Alexander de Cadenet is showing a new series of ‘Skull Portraits’ at the Saatchi Gallery this month. The ‘Medici Family Skull Portraits’ are based on photographs of skulls from the Medici Family tomb in Florence taken by Professor Gena in 1947 when the Michelangelo tomb sculptures were removed for safekeeping during the Second World War. The Medici Tomb in the New Sacristy was designed and in part created by Michelangelo and commissioned by Pope Leo X and Pope Clement VII (both Medici family members). Included in this series are photographs of the actual skulls of Lorenzo the Magnificent, Cosimo the Elder, Cosimo I, Eleanor of Toledo, and Giovanni di Bicci de Medici. The works are photographic prints onto dibond metal sheet each with painted quotes relating to the subject’s legacy taken from the subjects themselves, Medici Family mottos, or from Machiavelli on the politics of worldly power (as ‘The Prince’ was inspired by the life of Lorenzo the Magnificent).

This is de Cadenet’s fifth series of ‘Skull Portraits’ and the first where photographs have been used rather than X-Rays. For the first time too, text has been painted onto the image and the subjects have been given glowing ‘auras’, which are either the same colour as the skull or white. The quotations explore the darker, more ruthless side to worldly power, something still of great relevance today.

The Medici utilized and understood the value of art and culture in creating their legacy. This is, in part, why they are credited for creating the Renaissance. Some, especially the more famous among them, sought to be remembered many years after their mortal death. In this sense de Cadenet sees their skull and physical remains as being symbolic of what we know and remember of them many years later. Their remains were originally revered at a time when the ‘cult of relics’ was in full flood. This reverence is reflected in the extraordinary funerary architecture and monuments commissioned to house the relics. The relics can therefore be considered as the most essential and valuable remains of the subjects and that was the starting point for this new series of ‘Skull Portraits’.

De Cadenet says: ‘It’s fascinating to me that as an artist I can contribute in a small way to the ongoing legacy of the subjects, this is for me one of the more meaningful purposes of portraiture in that there is some transcendence from the finality and depressing nihilism of death. I also enjoy the paradox of presenting “who the subject really is inside” yet this also can be a mask, as you cannot recognise the person by looking at their skull. Ultimately all my art is about exploring what is giving my life meaning and, on this subject, a contemplation of mortality is a chance for deeper spiritual contemplation and questioning. The skull portraits can even hint at the more meta-physical dimension, the soul. What happens to the soul after death? Can the living still impact the souls of the departed? Maybe art can have some part to play in these eternal questions.’

Michael Forbes works with sculpture, installation, photography and digital media to explore themes of contemporary racial politics, migration, history, religion, and the dichotomy of blackness/ whiteness. His new works, exhibited together for the first time across three galleries at Djanogly Gallery, were conceived during Covid lockdown for Forbes’ MA in Sculpture at the Royal College of Art.

Forbes’ work explores current socio-political issues, with a particular focus on power, class, migration, national and international racial politics fed by the impact of capitalism, history and religion. He is intrigued by China’s exports of counterfeit designer goods, sold by African migrants on the streets of Europe for their financial survival. These relate to broader historical events, such as the increased presence of China in Africa, coupled with China’s domination of World trade and manufacturing. Issues of poverty and conflict in Africa have contributed to the increase of mass migration to other parts of the world, including Europe. Unprecedented numbers of deaths crossing the Mediterranean over the last 30 years have resulted from the attempt to get to Europe in the face of restrictions on entry. Forbes incorporates counterfeit goods into works like ‘12 Stations of The Masquerade’ and creates lightbox works based on photographs of shop windows (‘Shop… Selling the Ontology of Whiteness’) in order to comment on processes of valuation in relation to migration and trade. He is particularly interested in narratives that arise through the act of bringing the geographical, social and economic links of such sourced objects together.

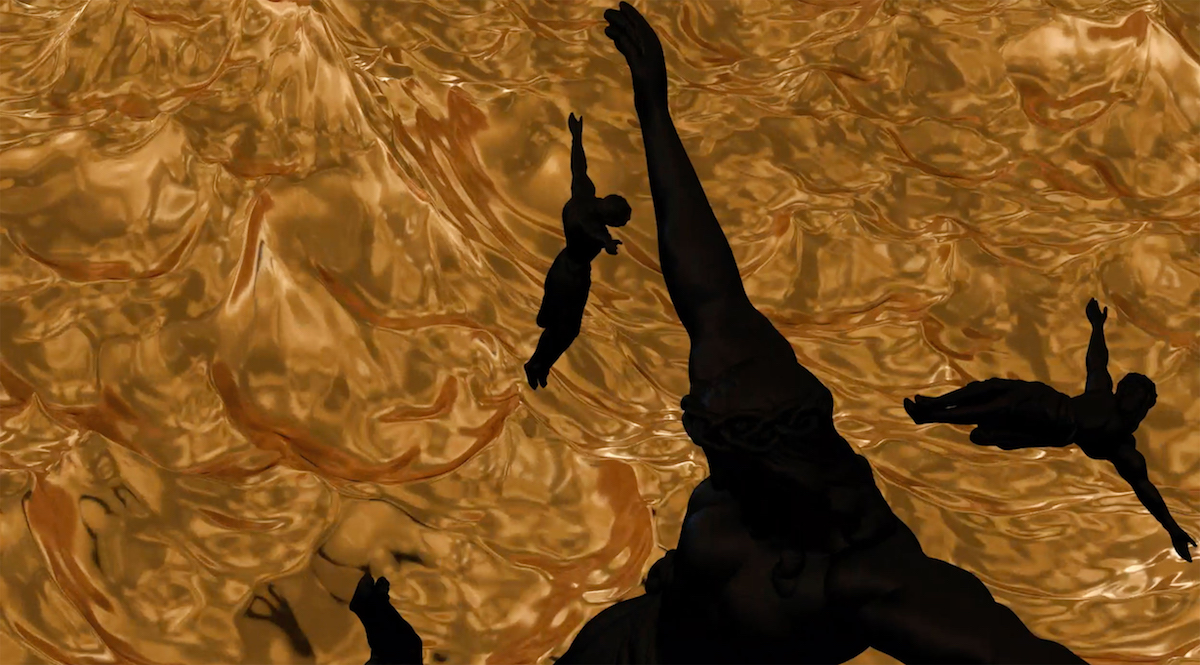

Forbes also comments on the importance and impact of religion on a range of citizens globally and how religion has been used to manipulate people into subjugation and exploitation historically, in ways which continue to impact today. That has been particularly so where the dogma that whiteness alone is inherently Godly has served as the basis for white supremacy. The largest sculptural installation here (‘Untitled I’) features dismembered cast figures of the crucified Christ in white, gold and pink suspended upside-down from ropes. The presence of life jackets on these inverted torsos points towards recent political and humanitarian events. These sculptures are presented alongside a video (‘An Eldorado of 512.6 million’) in which the same figures, now black, are tossed and submerged in an ocean of gold alluding to the economic disparities contributing to mass migration.

Within this socio-economic comment, Forbes’ primary focus is on the evolution of the ‘black body’; he includes a manifesto of Blackness among the works. His artistic practice began in photography and the exhibition features his photographic series documenting vibrant Caribbean Street carnivals (‘Carnival… beyond the glitz of the parade’). These images celebrate music, dance, fashion, and sexuality as they assert and unapologetically honour those who are under-represented.

‘Masquerade … evolution of the black body’ has a ‘12 Stations of The Masquerade’ plinth surrounded by totemic sculptures which Forbes has swathed and bound cocoon-like in shiny black PVC. The bulging skins of these conceal an assemblage of symbolic objects that, he suggests, have been consumed and processed in the evolution of the ‘black body’. Linked to these sculptures are those of ‘Untitled (white man’s burden)’, where white mannequins ride rodeo-style atop bulky PVC-wrapped parcels illustrating the precariousness of the white supremacist position. Alongside are the most obviously polemical works in the exhibition some of which reproduce slogans taken from the banners of demonstrators at the 2020 BLM protests whilst others replicate signs warning of the presence of surveillance cameras or the hazard of electrified and razor fences.

Curator, Rebecca Blackwood, notes that, through these works, Forbes ‘carefully and intentionally forces those of us who may have the best intentions to realise that we are infested with racism simply because we are white.’ For Forbes himself, she suggests, race enters his art ‘laying down routes for discovery, learning and understanding.’ On this basis, he ‘beautifully highlights for us’ existing social tensions.

While discussing church commissions with Neil Walker, Head of Visual Arts Programming at Djanogly Gallery (part of the University of Nottingham’s Lakeside Arts), mention was made of John Newling’s ‘Sing Uncertainty’ project for St Mary’s Nottingham in 2010. ‘Singing Uncertainty’ was an a cappella choral work where questions from hymns found in the hymn book used at Newling’s school were individually sung in the order that the questions appeared in the hymn book. Newling’s aspiration for this project was that when performed in St Mary’s Church, the space would be filled with the fragility of a longed-for certainty. The project drew on earlier initiatives involving the same hymn book including ‘Skeleton’ (1994) for All Saints Church, Newcastle Upon Tyne where the hymn book was edited to show only the questions that were written in the hymns and ‘Stamping Uncertainty’ (2004) where each questioning phrase was stamped each individually and each was displayed on 152 lecterns arranged in rows throughout the Chapter House of Canterbury Cathedral.

Another recent conversation also led to the discovery of a church exhibited book project exploring aspects of Christianity. Bernd Goering works sculpturally with old Bibles to create Bible objects – for example, a Bible with acupuncture needles stuck in it, a Bible as a lego brick, a cut Bible whose pieces form a cross – that make visible the different effects that the Bible had and still has. Goering’s Bible sculptures were most recently exhibited at Peterskirche Basel in 2019. The Revd Dr Chris Szejnmann shared the catalogue from this exhibition with me, as well as the conversations he has subsequently had with the artist.

Seeing these works reminded me of other book-based projects exploring aspects of religion. John Latham’s ‘God is Great’ series of sculptures are each “based on the three holy books on which three great monotheistic religions are based – the Bible, the Koran and the Talmud – reflecting the artist’s belief that all varieties of religious teachings share the same origins in the human psyche.”

Elizabeth Manchester has described the series:

‘In the first work, God is Great (#1a) 1990, the books are set in a broken, many-edged shard of glass mounted on the spine of a thick hardback book. In the second, God is Great (#1b) 1991, the three holy books appear to traverse a triangular shard of glass suspended in a metal frame. God is Great (#4) 2005 presents the three books lying in a pool of shattered glass, perhaps reflecting the global tensions that have erupted between people of different faiths in recent times.’

‘God is Great (#2) is a freestanding sculpture comprising a large glass panel mounted across the spines of five folio-sized hardback books forming a block in the centre. A cluster of three smaller hard-bound books appears to be protruding, at varying angles, through the glass in the centre of the work. Higher up on the glass a hole suggesting the profile of a half-open book has been cut, as though providing a slot for the addition of a further book. The three books are used editions of the Bible, the Koran and the Talmud. A smaller pale copy of the Bible has been slotted, whole, into a hole cut into one side of the larger Bible. On the other side of the glass, a smaller version of the Talmud has been stuck to the cover of the Bible. Fragments of text in Hebrew have been torn from the books and stuck onto the glass and parts of the books.’

Manchester suggests that, for Latham, ‘these books which claim to reveal the “truth” are the result of a subjective point of view which is always relative and never absolute.’

Linda Ekstrom, who has created altered Bibles since, at least, 1996, sees her work as being ‘anchored in the book, the book as a cultural and a symbolic object, and as a container of history, narrative and memory.’ She writes that: ‘The Bible, as the primary book of Western culture and central to my tradition, is the book I alter and transform into sculptures. One understanding of these altered Bibles draws from the Jewish tradition’s long use of Midrash, the interpretive mode which breaks down the scripture into phrases, then words, then letters to uncover meaning. I have thought of my altered Bibles as a visual way of looking at the activity of deconstructing text in search of meaning. As in Midrash, my altered Bibles insist that interpretation must remain open; they serve as visual symbols against fundamentalism, defying a singular, literal read by rearranging the order into myriad possibilities.’ She sees her altered Bibles as operating ‘within the tradition of religious iconography; they are a transformation of sacred word into sacred object.’

Willie Bester’s mixed media wall installation from 2000 entitled ‘Holy Bible’ juxtaposes two pairs of children’s shoes with a broken typewriter set within a frame and glass labelled ‘The Bible’ and ‘Holy Book’. Sotheby’s catalogue note suggests that Bester is using ‘the fragility of nostalgia as a signifier of the fragility of the mind of a child and the dangers of complacency in accepting without interrogation.’ Thereby, he ‘challenges the viewer to query memories and understandings that are assumed.’

Babel 2001 by Cildo Meireles ‘is a large-scale sculptural installation that takes the form of a circular tower made from hundreds of second-hand analogue radios that the artist has stacked in layers.’ Tanya Barson explains that the ‘radios are tuned to a multitude of different stations’ and ‘compete with each other’ creating ‘a cacophony of low, continuous sound, resulting in inaccessible information, voices or music.’ In describing this work, Meireles referred to a ‘tower of incomprehension’ and Barson notes that the ‘installation manifests, quite literally, a Tower of Babel, relating it to the biblical story of a tower tall enough to reach the heavens, which, offending God, caused him to make the builders speak in different tongues.’ This inability to communicate with one another ‘caused them to become divided and scatter across the earth and, moreover, became the source of all of mankind’s conflicts.’ Barson also suggests that Meireles has borrowed a symbol that is central to the writing of Jorge Luis Borges: ‘In his story The Library of Babel, originally published in 1941, Borges described a universe in the form of a vast or conceptually complete library that has its centre everywhere and its limits nowhere. This corresponds to Meireles’ interest in expanded notions of space and of infinity, in an excess of perceivable information and the processes of cognition.’

In 2017, Chiharu Shiota filled Berlin’s oldest church, the St. Nikolai Kirche, with black yarn that threaded through the space to create a thickly woven net in which thousands of sheets of paper pulled from Bibles in 100 different languages were tangled. The ‘Lost Words’ installation marked the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation and was linked to the history of Christianity in Japan. After Portuguese Christians came to Japan as missionaries in the 16th century, Christianity was banned and Japanese Christians practiced their religion in hiding. As a result, an oral tradition of the Bible developed in Japan with the Bible stories themselves migrating from person to person and the meanings shifting through retelling. The Bible passages used in this installation were chosen by the St. Nikolai Kirche and all pertained to immigration.

We could say that all these works, in words taken from Ekstrom’s writings, view the ‘biblical, historical traditions of interpretation, story, ritual, and iconography,’ ‘as open-ended and unsettled.’

Alexander de Cadenet: Medici Skull Portraits, StART art fair at Saatchi Gallery via West Contemporary Gallery, 12-16 October 2022.

Michael Forbes: BLK THIS & BLK THAT … A STATE OF URGENCY, Djanogly Gallery, 10 September – 6 November 2022.

Words: Revd Jonathan Evens Photos Courtesy of the Artists Top Photo: Michael Forbes El Dorado 1