In a world saturated with images, it becomes difficult to be captivated by visual content. Yet, I was taken by Christoph Wiesner’s last edition of Les Rencontres d’Arles, which I attended in early July.

I enjoyed my ritual of a cylo ride with Damien to La Mecanique General, where I visited Gregory Crewson’s exhibition. I have been a fan of Gregory Crewson’s cinematically staged photographs for years. There is a uniqueness in how he depicts suburbia in America, where melancholy, even darkness, is utterly aesthetic and romantic. Three bodies of works are exhibited in Arles: Fireflies, Cathedral of the Pines and An Eclipse of Moths showing the American middle class in a way that is definitely not “Great Again”. I could not agree more with the statement I read somewhere that Crewson was the hidden son of Edward Hopper and David Lynch.

Next door, Foundation LUMA celebrates Diane Arbus’s centenary of her birth with an ambitious exhibition gathering more than 450 images. Built as a labyrinth, I got lost sometimes in the maze of the installation, discovering and rediscovering Arbus’s iconic photographs.

Walking back from Luma to the city centre, I stopped in Croisiere and had a blast: I loved Dolores Marat’s photographs of her fleeting moments. She uses her camera with her instinct to capture emotions as a painter will use his brush: her work is full of colours and movement.

Upstairs in one of the rooms, Spencer Ostrander’s photography project, Bloodbath Nation, is a poignant memorial to the victims of mass shootings in the US. For two years, he travelled to over 35 sites in America to photograph deserted supermarkets, schools, and churches. The black and white photographs are eloquent: the void cries out for the lost lives.

In the next room, Céline Clanet’s beautiful black and white microscopic photographs of organic elements, which she collected in French forests, play with scale, allowing us to see the invisible.

Downstairs in Croisiere, Jean-Marie Donat has curated a moving exhibition, ‘Don’t forget me [Ne mobile pas]’, reviving Studio Rex’s archives and showing tens of thousands of photographs taken between 1966 and 1985 of North African migrants living in Marseilles. The exhibition is a tribute to all these men who crossed the Mediterranean to secure a better life for themselves and their families.

Collection Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto. Purchase, with funds generously donated by Martha LA McCain, 2015. Photo © AGO.

I continued my journey to Espace Van Gogh to see the much-talked-about Casa Susanna exhibition. In 2004, two antique dealers discovered 340 photographs from the 1950s‒60s at a flea market in New York City showing men dressed as women. It shows the underworld of the cross-dressers: like the other face of the « American dream » coin. These men, engineers, pilots, and civil servants created a space where they could freely exist in a suppressed society during a time of racial, sexual, and political segregation during Cold War America.

In l’Eglise des preachers, I smiled and even laughed at Riti Sengupta’s Things I Can’t Say Out Loud photographs of her time back with her family during COVID, experiencing the generational clashes with her mother in a very patriarchal family system.

One of the most poetic exhibitions I saw was Saul Leiter’s fragments of images: using a selection of photographs and paintings, most unpublished, Leiter created his own personal visual language. I must thank the artist and photographer Catherine Balet who pointed me to Saul Leiter’s exhibition. Once I visited the exhibition in the Archevêché, I could see how the American photographer resonates with Balet’s body of work which I discovered at Paris Photo last year.

Next door, in a small apartment which has not been renovated or touched for decades, Stéphane Gautronneau, in collaboration with Anne Clergue gallery, presented his exhibition « IMMAQA, a winter in Groenland ». I was mesmerised by his iceberg under the moonlight photographs. Not only do they appear unreal and surrealistic, but they became even more precious when Stephane explained the process of capturing the ephemeral light while facing extreme cold.

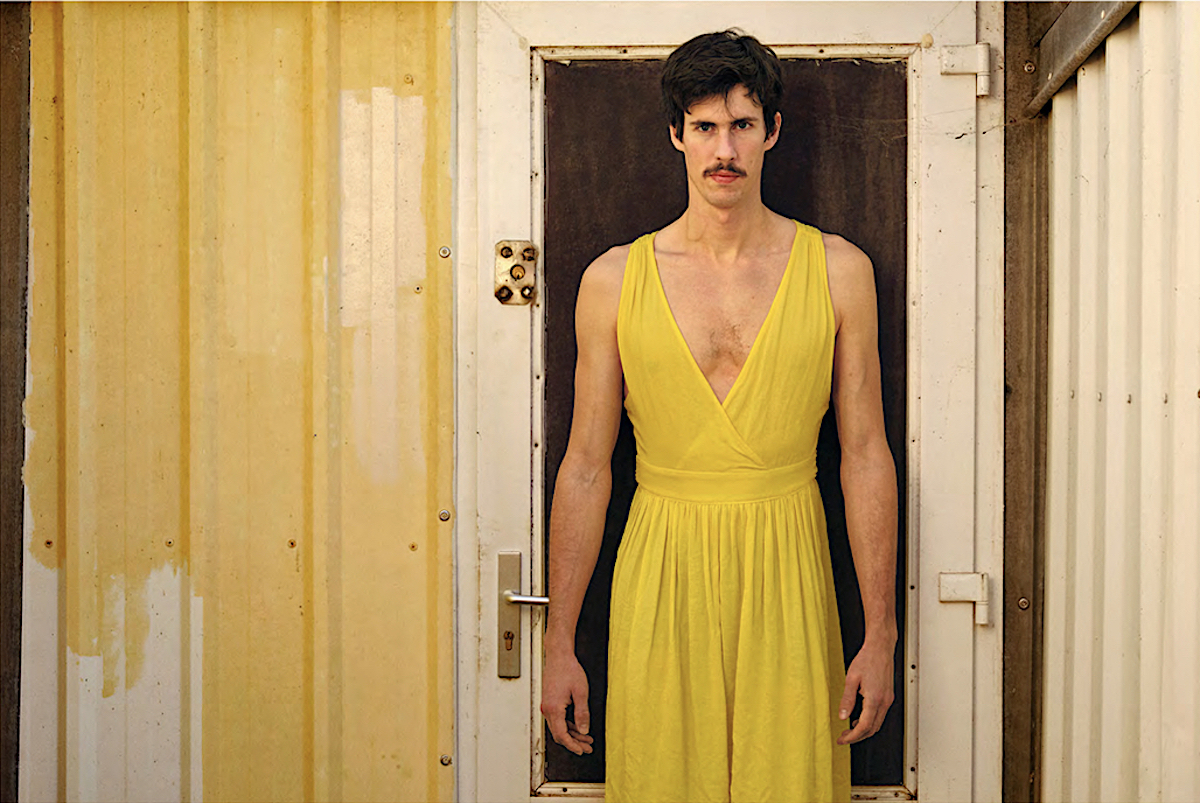

In French, « Les Rencontres », Arles is a meeting point where serendipity works in full swing. It was a pleasure reconnecting with Scarlett Coten, whom I met in 2016 when she was rewarded with the Leica Oskar Barnack prize for her work on the new masculinity. In her apartment in the centre of Arles, Scarlett showed me the male portraits she has taken for years in the Mediterranean regions, then in Trump’s America and recently in France, when she received the prestigious Ministry of Culture’s Grande Commission 2022: “Radioscopie de la France,” under the direction of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Coten offers the men she photographs a space where they can express their feminity. She contributes to the current Art historical debate on gender with her female gaze, never judging, only comforting. In her portraits, she takes control of her subjects only to allow them to regain their share of feminity. She deserves to exhibit her « trilogy » in one of the forthcoming editions of Les Rencontres d’Arles.

Before leaving, I met Stephane Noel, the Belgian photographer, at Le Galoubet, my base in Arles. He showed me part of his portfolio and explained the process he has been crafting for over ten years: photographs made with gum bichromate, a multi-layer process dating from the 19th century. As he explained, “It is the same process as painting except that you don’t add colour, but you remove it, and you put the light wherever you want so it gives you total freedom of interpretation like in music you have a score which is your negative, and you can make your interpretation…” The result gives depth to his unique photographs, which take about a week to 10 days to produce. In his Cuban miner’s portraits, he investigates the soul and reveals their humanity through the layering process.

I left Arles fulfilled, enthusiastic and ready to pursue my summer Art journey.

Lead image: Scarlett Coten: Adrien, Brest, France 2023