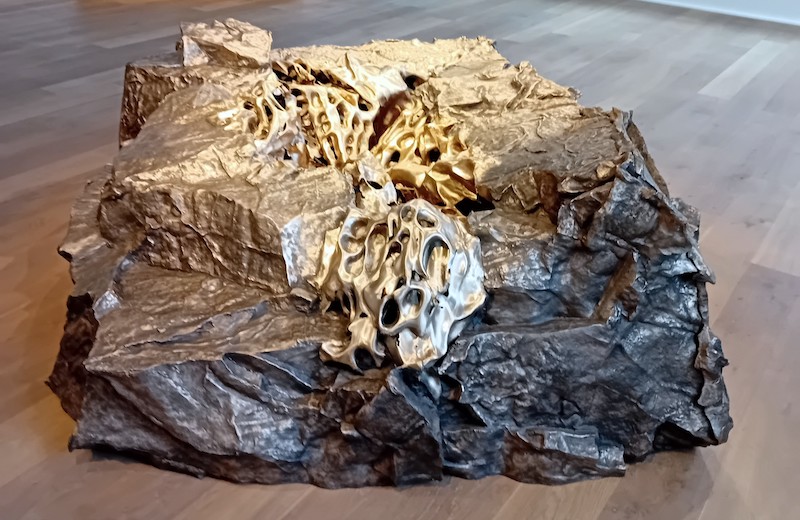

Over the past four decades, Spanish artist Cristina Iglesias has developed a sculptural vocabulary, creating immersive and experiential environments that engineer nature. Fusing the manmade with the organic, Hauser & Wirth’s exhibition ‘The Shore’ features three newly-created large-scale bronze works from her ‘Littoral (Lunar Meteorite)’ series, referencing rocks originating from the Moon that subsequently land on Earth. Mechanically-controlled water flows within them, establishing further connections to geological processes and increasing the temporal dimensions at play: the deep time of geology and astronomy; the time of the tides coming and going; the timing of the electrical controls; and human time, whether on the coast or in the gallery with the sculptures.

Installation view, ‘Cristina Iglesias. The Shore,’ Hauser & Wirth London, 2025, Photo: Damian Griffiths

PCK: How were these sculptures made?

CI: They are three single pieces, but I’m very happy that I could have this opportunity to place them together in this room and create a certain idea of a shore. They are fictional, but they are based on reality – the real memory of nature, imprints of rocks. My approach is more abstract and poetic than scientific. The fiction is the fact that they been removed from their original site, and also that the form is modulated, with different textures, and various parts are welded together to make a sort-of-collage. So it is always a certain perversion of the natural. Some are from meteorite rocks that form the limits of the oceans, but also, in the interiors that I create, from rocks as they are heated and eroded by salt and sun and weather. For each piece I cast the rocks into bronze, not as whole moulds, but as parts for compositions welded together. So they are invented rocks.

Installation view, ‘Cristina Iglesias. The Shore,’ Hauser & Wirth London, 2025, Photo: Damian Griffiths

And you work with a team, especially given that you make many large public works?

Well, I work directly on the pieces, but I do have a close team that works with me. Two of them are architects. There’s an engineer. There are other people. We have the main studio, and then what I call satellites that are a couple of foundries and workshops, that sometimes are in-house, and other times are developed in another place. But I’m always very close to the making. And I start with drawings and models, although I never just have a model to be copied, to be done in big. So we really model it with the final material, you know? So I could not make another piece exactly like one of these.

Cristina Iglesias: ‘Littoral (Lunar Meteorite) V’, 2025 – Bronze, water, stainless steel tank and water mechanism, 9 × 270 × 180 cm. Photo: Damian Griffiths

Some of the cast elements look a little like water?

That is not from the meteorites, but from the rocks affected by salt and the sun – also geological imprints, but they do have some water-like fluidity.

And water flows within?

It’s very much about the interior. The water is a measure of time. The works are kind of tidal, they fill and drain. They veil and unveil what is at the bottom. Each sculpture is a container for the water, the machine and the timings. As the motors have timers, they can be stopped if you wish and sometimes I do make a sequence – but here it made more sense to have a continuous flow. So there’s no beginning and end, but there is a sense of it being a cycle that you want to see through. And I’m very interested in pieces that are different from afar as opposed to when you get up close to them. Outside the gallery has a different aspect, as there is no sound from there. Inside, there’s the water and the vibration of the machinery.

How did you arrive at these works?

They relate to ‘Hondalea’, a monumental work located within an excavated lighthouse on the island of Santa Clara off San Sebastian, Spain – in my native Basque country, incorporating the peculiar geology of the Basque coast and the wild waters of the ocean that surround the island. And so the textures in London are taken from the meteorites of the Basque country. Inside the restored lighthouse, visitors can gaze into a sculptural configuration as water rises up, as if from the sea below, surging through forms cast in bronze, before pooling and trickling away. ‘Hondalea’ means ‘the depth of the sea’, and so that was to think about what is under what we see. That is a project connected to the defence of nature, of the seas and its coasts.

What is the aim of the combination of sculpture and interior water in ‘The Shore’?

The word ‘littoral’ refers to something relating to or situated along a coast or shore, or the region where the land meets the water. The geological time of our planet can be perceived in the coasts, and the meteorite appearance of the work symbolises the collision of outer space and Earth. They are very geological, you can see the many years of time. The idea is that it is a new landscape, but somehow attached to the memories we have of every landscape. And they have the memory of water. And water is a sign of life. I’ve been thinking about how everything is related. And these are interiors of that sea; the interior, of course, of rock; but they could also could be the interior of a body. And all these relations between meanings are within them.

Detail view, ‘Cristina Iglesias. The Shore,’ Hauser & Wirth London, 2025. Photo: Paul Carey-Kent

I find myself circling round them as sculptural forms but also wanting to look inside to see how the water flows, making them act like rock pools and suggesting an interior world …

I think so, yes, and there’s something quite visceral and bodily. They can seem gentle, but that’s like a rocky coastline: it can be calm, and it can be wild and intense. And while you somehow recognise the vegetation or mineral world, that is also a portal to another world.

Can I touch?

Yes, visitors are welcome to touch them, explore them, sit on them…

Cristina Iglesias: ‘Forgotten Streams’, 2017 – Bronze, water, stone, stainless steel and hydraulic mechanism. Photo Thierry Bal.

Also in London, people can see ‘Forgotten Streams’ (2017) at the Bloomberg headquarters, where The City’s lost river, the Walbrook, once ran. Three pools of water are connected to flow across sheets of bronze that are moulded into a riverbed of intertwined tree roots, leaves, mud and vegetation. That recreates the sense of a tidal river flowing under the building, so the visiting public can imagine a London from a distant time. What led to that?

I’m very interested in responding to a place, and I’m very interested in the city, in how we move in the city and in time. I like to do pieces that maybe stop you, and oblige you to give more time to looking or more time to wonder, and maybe call you to, to go again – and see if something that you saw is happening again, or could happen again. I see it as a place of gathering and recollection of all the constraints the city gives you, transforming that into something meaningful. I hope it feels welcoming, with the strategic impact of drawing people away from building into forecourt. There’s a memory of the history of the place, but also the chance to create a new memory.

‘Cristina Iglesias: The Shore’ runs 14 Oct – 20 Dec at Hauser & Wirth London. ‘Forgotten Streams’ is permanently viewable 24 hours at the Bloomberg headquarters. All works © Cristina Iglesias, VEGAP, Barcelona, 2025. The answers above come from in-conversation events at the gallery as well as my direct questions.