It’s been hard to choose a single painting by Frank Bowling for this series, to select one that is more significant in his long and illustrious career than any of the others. Each time his style has changed seems to have been a significant moment. His recent Tate one-man show illustrated the breadth and reach of his stylistic concerns.

Mirror (1964-66) is undoubtedly a seminal painting. It was done by the young Frank when he was a student at the RCA. This statement alone is significant. There weren’t many black students studying at this bastion of British art in the 1960s, even though, at the time, the college was spawning the future stars of British pop art, including David Hockney, Allen Jones, Patrick Caufield, RB Kitaj and Pauline Boty. It was 1953, and Frank was 19 when he arrived in Britain from Guyana, planning to be a poet. However, whilst doing his National Service in the RAF, he met the artist Keith Critchlow and decided to become a painter. Social change was in the air. The war was not long over, and Britain was struggling to rebuild. Old class divisions were dissolving, with working-class heroes like Terence Stamp and David Bailey making their mark. But it was still a predominantly white society, not the easiest milieu for a young black man to become a successful painter.

it seems to suggest that art has a higher purpose than mere fame.

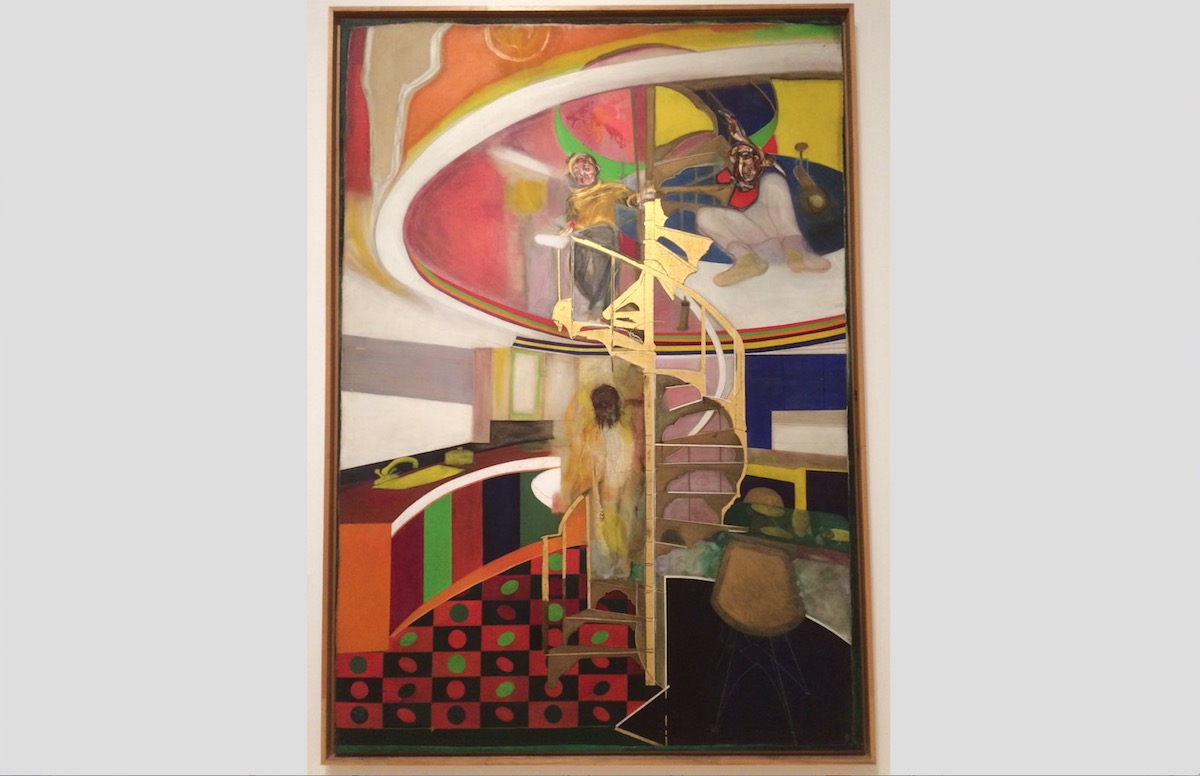

Mirror is painted on plain weave, medium-weight cotton duck canvas with sections of duck cotton and linen glued around the edges, there’s no priming layer, and the outlines of the Eames chair and kitchen cabinets were masked off before painting. At the centre is the Royal College’s spiral staircase. Frank appears twice. Once at the top and once arriving at the bottom. The staircase was, apparently, the favoured route for students escaping tutors who came to see what they were doing in their studios. Half-way up is the blurred figure of Bowling’s then-wife, the writer Paddy Kitchen. The painting draws on a number of styles. The op art of Victor Vasarely and Francis Bacon, whose influence can be seen in the arrangement of figures at the top. Bacon was a friend, and Bowling has confessed that not only was he trying to ‘marry-up’ different styles but that he was trying to ‘outdo’ Bacon. Still, at this point, he didn’t align himself either with figuration or abstraction, rather wanting to make works that were geometrically complex. But Mirror is not simply an exploration into painterly styles. It was personal. It showed Frank caught between two worlds. A reminder of the dangers that lurk on the Snakes and Ladders board, where success is never guaranteed, and the long climb upwards is always fraught with danger. It is a painting about belonging. Bowling had every reason to feel a degree of anxious exclusion. Touted for the Gold Medal, he was pipped at the post by Hockney (Bowling won silver), while his relationship with Paddy Kitchen, who was both a member of staff and white, was sufficiently frowned on for Bowling to leave the Royal College for a period at the Slade.

It also seems likely, though I can find no mention of it anywhere, that at some point, he must have looked at Jacob’s Ladder by William Blake. The story in the book of Genesis, chapter 28, verses 10-19, states that while travelling, Jacob went to sleep one night and dreamt of a ladder where angels were ascending and descending to heaven. In the dream, God spoke to him, saying that the place where he was sleeping would be given by him and his descendants and named Bethel. Blake was the first known artist to use a spiral staircase instead of a ladder to bridge the gap between heaven and earth. Rembrandt did a version with a straight ladder in 1655, and in 1665 Salvator Rosa depicted a ladder crowded with angels. There’s also a carved version on the outside of Bath Cathedral and more recently, Helen Frankenthaler explored symbolic shapes that morph into an exuberant figure climbing a ladder.

Looking carefully at Mirror, it seems impossible that Bowling did not know of Blake’s version. The flow and curve of the staircase repeat those of Blake’s, while the figures at the top hover beneath a circular heaven-like dome. This suggests that this wasn’t simply a painting by a young black painter with ambitions to reach the top of his profession but a work highlighting his aesthetic and spiritual aspirations as an artist. Painted when he was 30, five years before he was awarded a solo show at the Whitney New York, it seems to suggest that art has a higher purpose than mere fame. It might almost be a message to himself to hold faith. Because of his skin colour, he knew that he was bound to face adversity and that the only way to deal with it was to look up, keep climbing and remain true to his vision.

The move to New York in 1966 brought about a loosening of his ties with figuration to embrace sublime colour field paintings that combined a sensibility towards American Abstract Expressionism and the improvisations of Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman with the veils and fluid transparencies of Turner. From the mid-1960s, Bowling stopped using traditional oil paint and experimented with a broader range of materials and techniques to create his Map paintings. Here abstraction merges with political concerns and his growing interest in a post-colonial language and his Afro-Caribbean roots. Experimenting with a variety of techniques, he poured, tipped and sprayed paint onto his canvases, observing how the material could be manipulated and how chance might play a part in the creative process. ‘It all happens,’ he’s said, ‘ in an extemporary way. I mean I don’t have any pre-planned idea of how I am going to make a painting’.

And of Mirror, he’s said, ‘I mind an awful lot about this picture. It is a very personal work’. It certainly is. One that explores many things. His treatment by the RCA and his resentment at Eames’ liaison with his wife Paddy Kitchen, his ambivalence about being a black man in a predominantly white world, along with the love of his medium. It also reveals a deep interest in art history and, like Blake’s painting, firmly makes claims for the transcendental possibilities of art.

Sue Hubbard is a freelance art critic, award-winning poet and novelist. She has two recent poetry Collections. Swimming to Albania www.salmonpoetry.com and Radium Dreams is available as a book and forms part of a major exhibition at The Women’s Art Collection, Murray Edwards College, Cambridge and is available here:

Her fourth novel Flatlands is due from Pushkin Press in June and from Mercure de France as Le Ciel Si Vide, in April. It is available here: