It takes a long time to reawaken a slumbering giant, forty years in the case of the Battersea Power Station. And remaking the giant’s bed, all 42 acres of redundant urban gash space, a substantial chunk of urban regeneration in the heart of London, is a task that will remain a considerable time in progress. But now the bones and much of the flesh and spirit of the development are in place and its heart, the power station, slowly beats again. So it was time to mosey down and take a look at the old bird in its new finery and its new, still-rising up-market neighbours.

Forty-two acres are a lot of acres to develop, to create anew a dense, close-knit and legible piece of urban fabric, with all the services, road layouts, public spaces and, of course, buildings that will comprise it. Begun in 2013 after a few false starts, it is not surprising that it is only about half complete. But there is more than enough on the ground to get a reasonably accurate feel of the place and to gauge the success or otherwise of the new architecture and place-making.

The power station’s new environs have been laid out roughly in accordance with a master plan formulated by the late Rafael Vinoly (architect of Fenchurch Street’s unfortunate Walkie Talkie) and so far realised by four principal architects. Wrapping around the west side of the power station is the main residential Phase 1 block (the power station being Phase 2) by SimpsonHaugh and De Rijke Marsh Morgan architects. South of the power station up to Battersea Park Road Phase 3, around two-thirds complete, comprises the residential and shopping blocks by Foster and Partners and Frank Gehry Partners and the new underground station. Phases to the east remain to be commenced. Between the power station and the Thames, a new public park by LDA Design and Andy Sturgeon presents the power station with a new forecourt for its principal north view from across the river.

Let’s begin here, at the lynchpin and heart of the new development. Battersea power station is one of that select group of buildings that can truly be called iconic, unlike the rattery of apartment blocks springing up all over the place that now goes by that devalued appellation. It is a magnificently idiosyncratic beast of a building, four industrial smoke stacks sitting atop a colossal plinth of the sparest art deco brickwork, one of Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s last gigantic edifices (Liverpool Cathedral, Bankside Power Station), built in two stages, from 1929-1935 and 1937-1955. The blurb about its volume is hard to believe, but I must assume it to be true that the whole of St Paul’s could fit inside the central main boiler house. Instead of St Paul’s, this has now been filled by a leisure centre and six floors of office space around a central atrium, all 500,000 sq ft (that’s equivalent to the total floor area of the Gherkin) taken by Apple.

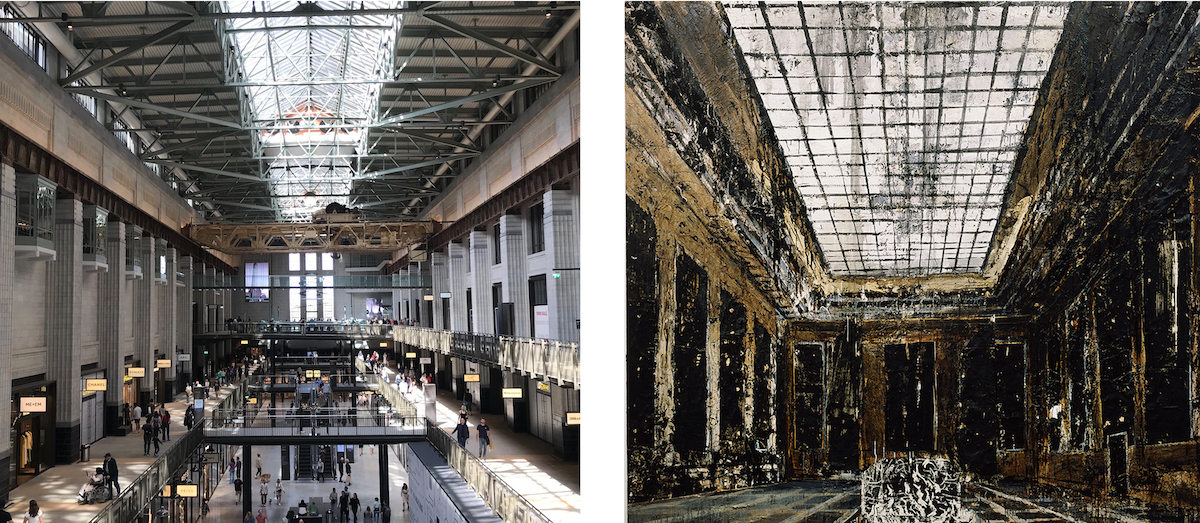

Flanking the central boiler house volume are two shopping malls, originally turbine halls. In essence, the building comprised three vast volumes once filled with equally massive turbines, overhead gantries, boilers, pipes, do-dahs and banks of analogue dials and switches which a long, long time ago were the model for the consoles of interstellar Buck Rogers spaceships. A muscular, no-nonsense prototype of the future once envisaged by Jules Verne and HG Wells. That’s what I encountered on an office visit before it’s expected imminent demise in 1983 when analogue still ruled. Then the power it once generated was raw electricity, whereas now it’s the slippery, intangible power of the digital and the brash power of retail consumerism that’s taken over. Much of the original architecture that symbolised this power, the purpose of the building, remains externally unavoidable in its massing, internally in the volume of the spaces. But one feature, now subservient to the commercial clutter of the two malls, when noticed, evoked with some clarity two different powers of a former age, the beautifully preserved colonnades of sparsely detailed, faience-tiled classical pilasters that line the multi-level shopping malls. Looking down from the far end it suddenly brought to memory my standing before Anselm Kiefer’s majestic painting of Albert Speer’s ruined Reich Chancellery (Interior, 1981) at the RA’s Kiefer exhibition in 2014; a memory of a painting of a memory. What Martin Gayford describes as ‘a painting of spectral, sinister magnificence’. A perfect example of the classical orders’ ability to evoke power, whether electrical, cultural or political and of two-dimensional painting’s ability to conjure the metaphorical while architecture can only suggest it. But I digress.

However, faience cannot compete with neon and the clarity of the colonnades has been partly obscured by the projections of the shopping levels. And while the overhead gantry on its steel tracks and the roof trusses have been retained and the size and shapes of the turbines indicated in the mall floors, these vestiges and palimpsests of the past are unable to hold their own against the glossy brashness of modern retailing, with the predominance of so-called luxury goods threatening to reduce the interior to no more than a simulacrum of an airport duty-free lounge.

On the whole, however, the architects WilkinsonEyre have formulated and achieved as good a conversion and conservation of the original building as could be expected, keeping in mind that the loss of much of the impact of the voluminous interior (one of the building’s greatest features) was inevitable. Cleverly, a glimpse of the principal boiler house volume has been provided by stopping the internal infill short of the end walls; the retention of the original control rooms has provided the complex with two glamorous art deco function rooms that, being all dials, switches, marble and coffered glass ceilings, have become time capsules to a bygone age; the additional rooftop residential accommodation sits very well on the mass of brickwork below; the insertion of an enfilade of long vertical windows in the flank walls to service new residential accommodation certainly does not harm the original; utilising the northwest chimney for a viewing lift offers not only spectacular views but also surprises by revealing the massive size of the chimneys, with a maximum internal diameter an astounding 8.5m and the discovery that while looking quite circular externally they are oval. The meticulous restoration should not be forgotten either; notably: 1.75 million handmade bricks were sourced from the original brick manufacturers, and the 50m high chimneys (total height 109m) were dismantled and rebuilt in the original hand-poured concrete process.

Circus West Village See Top Photo

So let’s escape what, to the public, has become yet another enclosed shopping centre. What of the outside? What of the new quarter born of the power station’s near-death throws? The Phase 1 development stands closest to the power station and forms part of the principal view of the complex, the north side. The masterplan envisages this as a tableau, the stately power station, cleaned and repaired as gleaming new, revealed (ta-dah) in all its glory by two flanking residential blocks that peel away like stage curtains. As an urban set piece, it’s appropriate and works. The main challenge, however, is the treatment of the new flanking buildings – do we treat them like Edwardian stage curtains, all rich velvet, brocade and swags, or like neutral net curtains? Not forgetting that the building will be in full view of what will feel like the whole of London on the opposite bank. The latter has become the standard modernist approach, to step back and let the main event take centre stage, contrasting the materials, style and texture of the new to distinguish the old, to make clear what is the original and what has come later. Indeed, Historic England stipulated that all new neighbouring buildings should not be in face-brick, no doubt for this very reason. So the architects of the now completed Phase 1 west side, Circus West Village, followed suit but unfortunately went too far. Centre stage stands the spare, elegant and finally modelled brick monumentality of Giles Gilbert Scott’s original. To the right, a cliff face of loosely faceted multi-storey slabs of glass that, against the evident attention to design and, surely, belief exhibited in the original, looks lightweight, incoherent and wrong. Glass has become the universal go-to material for architects when approaching the confines of a listed building; it is neutral, distinguishable from the inevitable masonry of the original and, supposedly, transparent. But in this case, the cumulative effect is one of a vague, somewhat uncouth disrespect, as if the glassware is embarrassed to be there at all. By all of today’s tenets, the approach that the architects of the new building took was the correct one. It is a tough call when building anew adjacent to the venerable old, an architectural commission that could be called a hospital pass in rugby parlance. But here, glass alone was not enough – what happened to design, form-making, balance, composition, movement, to all those things that go into design?

All those things in excess on the opposite side of the power station, in Frank Gehry’s crazed take on John Nash’s Regency stucco. I kid you not, but more on that in a moment. So far, only two of Gehry’s five blocks, called Prospect Place, are complete, with work continuing on the remaining three. Foster and Partners’ long sinuous wave, the Skyline building, closes off the western boundary of Phase 3 so that three linear building strands radiate southwards from the power station’s main entrance, with a pedestrian shopping street, Electric Boulevard, running between the Foster and Gehry blocks and a private park separating the two strands of Prospect Place. Running alongside Prospect Place on the east is Prospect Park and the broad footpath to the new underground station. That’s how I arrived and approached the whole shebang on my first visit. It is a confusing ‘shebang’ the first time, with the untidy southern end of Prospect Place hoarded off and under construction giving way to the completed buildings, which look more like a collapsing blancmange than blocks of flats – sorry, apartment blocks. Proceeding along this way, the power station heaves into view around the bend in the footpath while Gehry’s building shambles on to terminate by pressing up against the power station in a dramatic, almost medieval way, the way tight streets cram up against gothic cathedrals on the continent. Architecturally, it’s a stand-off. If anything the immovable monumentality of the power station wins, the three prongs of Prospect Place and Foster’s Skyline drawing back ever so slightly to form a neutral double-level piazza to keep the new apart from the old.

Gehry’s geometry belongs to a parallel universe and can be alien when first encountering it. As I have before, at the Louis Vuitton gallery in Paris, Bilbao’s Guggenheim and Sydney’s University of Technology’s Business School. So this was my fourth discombobulation at the hands of the nonagenarian (can you believe it?!) maverick and I should have known what to expect. So, perhaps unsurprisingly, this is what I wrote after my first visit: ‘His two blocks display all the usual contorted sculpture that he was no doubt commissioned to produce. Which, conversely, makes the twisting bulges of the facade rather predictable and hackneyed. And synthetic, as if they were designed by AI loaded up with Gehry’s patent algorithms. The complex 3D cream-coloured cladding doesn’t help, either; whatever it is made of looks like plastic and hence unconvincing, like a stage prop, its bulging creaminess reminiscent of an overweight American plumped on a beach or the Krispy Kreme giant in Ghostbusters.’ With apologies to Americans. By the way, that’s Gehry’s link to John Nash – the cream-coloured Regency stucco being the inspiration for the colour of the cladding.

But I decided to take a second look and this is what I think now. I’m still uncomfortable with the cladding colour and anyway, it’s too white for stucco. And the angular grey framed winter gardens, while a great feature to the interiors, sit uncomfortably over the curving cladding and look clumsy externally. But when standing in the garden between the two buildings or looking down Electric Avenue with the Foster building on one side, or approaching the power station from the south, the sheer crazy vivacity of Prospect Place’s contortions takes over. They soon insinuate themselves into the viewer and once familiarised, one gets on with one’s business. However, the subliminal perkiness one may feel might owe more to the street scene and Gehry’s joie de vivre than that coffee – you know, the one you had in that coffee bar cut out from the sales brochure. And from what I saw, the Joie has produced some pretty spectacular interiors as well. All the while, the Skyline building facing Prospect Place keeps it in place, standing politely back to present a grandstand view of the pyrotechnics before it. Against Gehry, it looks conventional (what wouldn’t?). Still, it’s got enough going on and its modulations fit nicely around Gehry’s so that the two combine to give the new Electric Boulevard an excellent sense of movement. Soon Phase 3 will be completed, and with it will come what promises to be a truly spectacular creation, the central circular ‘Flower’ of Gehry’s quintet.

For a peering visitor, especially an architect, Frank Gehry is outstanding value – he gives so much, always in a fun, devil-may-care, to-hell-what-others-think way. But it’s an architecture, as Gehry insists, that is rooted in the principles of art rather than those of commercialism, even though it serves that master very well and if the recourse to art is sufficient. It’s glamorous, but is it vacuous? What I wrote on my first visit has more than a grain of truth, but the joyfulness of his architecture, or the brashness, should one prefer, tends to reduce it to churlish quibbles.

There are two stars in this still-rising new quarter of Battersea and they stand confronting each other across a vast divide in time, technology and culture, Scott’s power station and Gehry’s Prospect Place. Both buildings are icons of their age and born, in part, of an almost naive belief in a future bathed in the benefits of two completely different technologies: the one of raw, physical power generated by machines, the other invisible, deceptive and capable of much, much more than producing complex geometries. Scott’s was erected in the shadow of war and in the style of the age also espoused by fascism. Would it be facile to suggest similar outcomes for today? Although there is a nagging sense of the 30s ‘let’s forget and get on with the party in Gehry’s work.’

Alex Murray 17/5/2023