Artist/activist Harmony Hammond was born in Chicago in 1944 and is associated with the feminist art movement in New York during the 1970s. She has lived and worked in New Mexico since 1984.

Hammond’s work combines gender politics with both minimal and post-minimal sensibilities

Hammond has had over 30 solo exhibitions, many international. Her work combines gender politics with both minimal and post-minimal sensibilities. Her materials are an essential part of her practice. Hammonds work falls somewhere between the disciplines of painting and sculpture. She says, ‘I’ve always been interested in bringing sociopolitical content into the world of abstraction. Incorporating materials and objects, with their geographies, histories, and associations is one way of doing this.’ Her work is included in the current Exhibition ‘Women In Abstraction’ at the Guggenheim, Bilbao.

PCR) How would you define your practice during the period when you created your floor pieces? Describe

HH) In the early 70s, I and many other feminist artists abandoned the male-dominated site of painting and consciously began using materials, techniques and formal strategies associated with women’s traditional arts and the creative practices of non-western cultures, precisely because of their marginalised histories and associations. Underlying this practice was the belief that materials and the way they are manipulated bring meaning into works of art.

PCR) Who would you cite as your seminal influences?

HH) At that time, I’d have to say Eva Hesse. Her post-minimal latex rubber and fibreglass sculptures referencing the body had a profound influence on many feminist artists, including myself.

PCR) At first glance, your floor pieces mimic traditional braiding methods used in vernacular handicrafts. However, you have described them as paintings rather than rugs. Why?

HH) In 1973, I created a series of seven-floor paintings made out of knit fabric my daughter and I picked from dumpsters or left curbside in big plastic bags in the garment districts of lower Manhattan. Strips of the fabric were braided according to traditional braided rug techniques, but slightly larger and thicker in scale, coiled, stitched to a heavy cloth backing and partially painted with acrylic paint, the “braided rug” literally and conceptually becoming “the support” for the painting. Referencing rag rugs, but non-functional as such, the Floorpieces occupied and negotiated a space between painting (off the wall) and sculpture (nearly flat), although, because of my painting background, I thought of them primarily as paintings. Approximately one inch high and five and a half feet in diameter, five of the Floorpieces were to be placed directly on the floor and shown as an installation without anything on the walls, thereby calling into question assumptions about the “place” of painting. Due to the space limitations of such a large landmark historical exhibition, “Women in Abstraction” was only able to present three of those five Floorpieces.

PCR) The lines between fine art and applied art has blurred since the 1970s. For example, Annie Albers described herself as a weaver. Do you feel you could identify with this description in the 21st century?

HH) That line didn’t always exist. Women artists of the Russian avant-garde and the Bauhaus, including Annie Albers, worked in diverse mediums, consciously exploring the link between fine art, applied art, and craft, including weaving, textile design, bookbinding, graphic arts, clothing, jewellery, costumes, stage sets, puppets, rugs and furniture in addition to dance, photography, painting and sculpture. The exhibition “Women in Abstraction” demonstrates the centrality and importance of their work to those movements. In the U.S., male and female artists were, for the most part, treated equally until the status of women shifted after World War II and the art historical narrative of Abstract Expressionism, constructed to emphasise the work of male artists, minimised paintings by Lee Krasner, Joan Mitchell, Elaine DeKooning, Janet Sobel, and later Grace Hartigan, Shirley Jaffe, Helen Frankenthaler, and others, sidelining their work to the margins of the white male mainstream. Additionally, any work that reflected women’s experiences in the world was ignored or trivialised.

Fast forward to the early 1970s, when feminist artists, such as myself, challenged that narrative by intentionally blurring boundaries between art and craft and making work that referenced women’s lives and creative practices. I was trained as a painter, so think of myself as a painter, but feel free to work with any and all materials. Stitching, weaving, braiding, wrapping, knotting, etc., are techniques I reference or utilise as want or need be. The sewing basket is just another toolbox.

PCR) (I know this is a question that you must be asked a lot, but could you) Describe what it was like to live in New York in the 1970s? Our younger readers romanticise it; however, I remember it as a city in deep decline that was a creative hub because you could share a cheap studio space downtown, live off a part-time job, and still have time to be a maker.

HH) In 1969, I moved from Minneapolis to lower Manhattan. Back then, it was easy to enter the city as a young artist and meet your expenses with a halftime job. For years, I worked as a storyteller for the Brooklyn Public Library, bringing books to 3, 4 and 5-year-olds in daycare centres in Williamsburg and Bedford Stuyvesant. I was the story lady. The kids thought I lived in the library. I didn’t start teaching at the University of Arizona until 1988 after I had moved to New Mexico, but even then, I only taught one semester a year, so I had time for my own work. That’s always the choice I’ve made – less income, but more time for my work.

I was fortunate to be in New York at the right time. The late ’60s and early ’70s were a period of civil rights and anti-American-Vietnam War activism, the beginning of the gay liberation movement, the second wave of the feminist movement, and the birth of the feminist art movement. I was influenced by and contributed to early feminist art projects. It was also a period of post-minimal interdisciplinary experimentation with materials and processes, resulting in work that was both conceptual and abstract. Artists moved back and forth between painting, sculpture, video, dance and performance, calling it one thing one day and another thing the next. Feminists brought a gendered content to this way of working.

There were few places to show our work, no market or critical interest, so everything was wide-open and possible. We had nothing to lose. Interested in having “space” and “voice”, we created artist-run exhibition spaces, slide registries, art journals, and art schools such as A.I.R., the first women’s cooperative gallery in N.Y.C., Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art & Politics and the Feminist Art Institute, to name a few. It was an exciting and empowering time.

PCR) How has your creative process evolved 1970-Now? Briefly Trace your breakthrough Floor Pieces through to the work you are producing today?

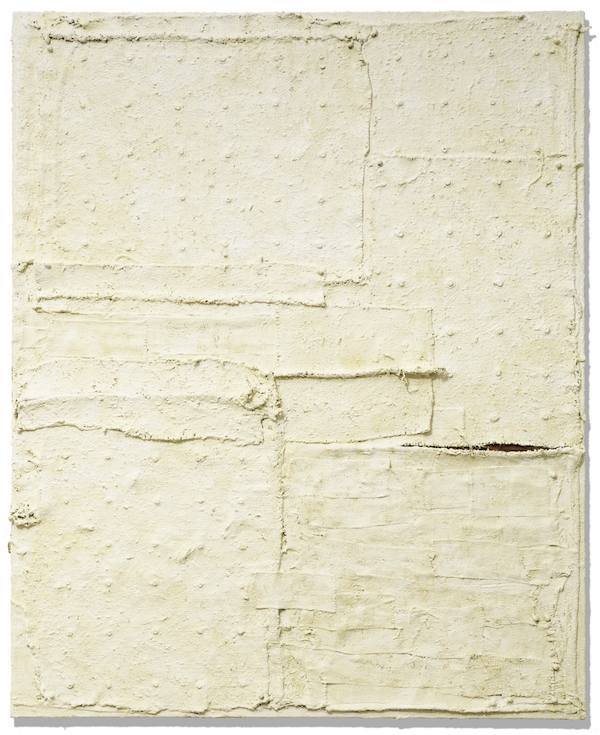

After the Floorpieces, I returned to painting, but on my own terms. In 1974, I began a series of small paintings that looked as if they were woven out of paint. The surface was slowly built up with successive layers of oil paint mixed with Dorland’s wax. Weave patterns were obsessively incised into the paint. The resulting surface was irregular, lumpy and bumpy, emphasising the painting surface as skin and indirectly the body. Looking beautiful and woven from a distance, almost monochrome, up close, the under layers of colour were exposed and little points protruded from the surface of the painting. These points were at once menacing and fragile. Referencing weave patterns found in textiles and basketry, I was able to take the feminist project of creating an historical narrative of women’s creativity back into the painting field, merging traditional and fine arts in the skin of paint.

Over the years, what followed were a lot of mixed-media works utilising cloth, straw, hair, metal gutters and corrugated roofing, linoleum, and other non-art materials, as well as latex rubber and oil paint. The work continues to occupy a space between painting and sculpture, what we might call expanded painting. Visual strategies I employed in the ’70s and ’80s such as accumulation and layering; under layers revealed or asserting themselves; piecing and patching with connecting strategies visible; a focus on edges and seams; and the manipulation of the materials to activate the painted surface, continue to this day.

For the last decade, I’ve made large, thickly painted near monochrome wrapped and grommeted paintings that suggest the body or bodies negotiating for freedom. They engage with and disrupt the history of modernist painting – specifically narratives of abstraction and monochrome. Coming out of the post-minimal and feminist concerns with materials and content that I’ve been talking about, versus modernist reduction, they upset the rhetoric of formal purity by flaunting seams, sutures, flaps, tears, holes, patches and frayed edges, all of which bring meaning to the work. In my Bandaged Grid and Chenille paintings, under-layers of colour are visible through grommeted holes and split seams, as well as surface cracks and crevices in the painting surface. It’s about what’s hidden, buried, revealed, pushing up from underneath, agency – the painting surface under stress.

PCR) How did your inclusion in the Pompidou and Bilbao exhibitions come about?

HH) Christine Macel, curator at the Centre Pompidou where the exhibition originated, contacted Alexander Gray Associates, the N.Y.C. gallery that represents my work. When she was in the city, we met and discussed the exhibition. While nearly all my work is abstract, Christine was interested in the Floorpieces which she saw as central to the dialogue between fine art and crafts, and the development of a feminist abstract art in conversation with work by women artists of the Russian avant-garde and the Bauhaus, “fibre artists” such as Magdalena Abakanowicz, Lenore Tawney & Sheila Hicks, as well as painters from Sonia Delaunay-Terk to Lee Bontecou and my contemporaries such as Howardina Pindell and Elizabeth Murray.

Harmony Hammond Interviewed By P C Robinson © Artlyst 2021 Top Photo Artlyst 2021