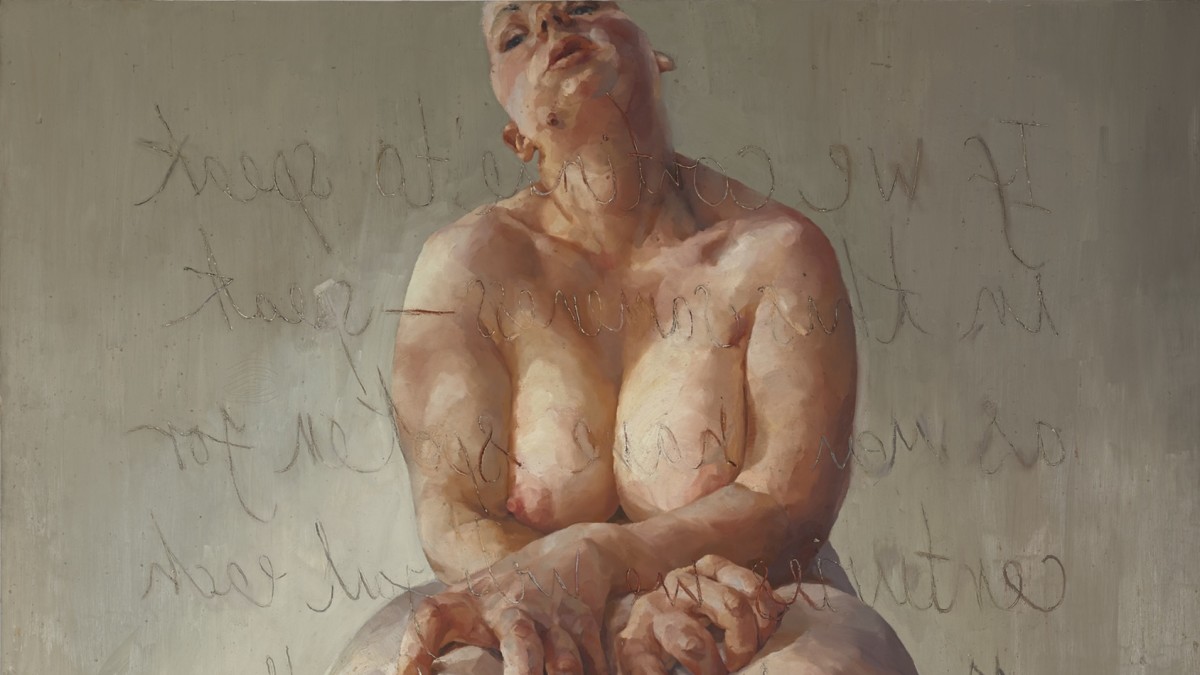

She sits balanced on a high stool naked in front of a mirror, her white sling-backs hooked around its slender neck to balance her heavy body. Her bulbous breasts hang to her waist. Her head is thrown back, eyes closed, hands clawing at the flesh of her ham-like thighs. Scribbled into the paint, in mirror-writing like graffiti reminiscent of Cy Twombly’s scrawls, are gobbets of text by the Belgium feminist writer, Luce Irigary that say: If we continue to speak in this sameness – speak as men have spoken for centuries, we will fail each other.

I first discovered this painting in a group show – I can’t remember where

Not long after Jenny Saville had left art school in Glasgow. As yet she was unwritten about and unknown. I was taken aback by its power and wrote a short review for Time Out. The work was determined, muscular and quite literally ‘in yer face’. It was obvious, with its Freudian undertones (both Sigmund and Lucien) that this young artist was destined to go far. So it’s interesting to revisit the work that brought Saville to the attention of the artworld, nearly 20 years later.

For a young woman, at the time, to insert herself into the male canon of Titian and Rubens was highly audacious. Few women had painted the female nude with such candour, though the likes of Suzanne Valadon and Paula Modersohn-Becker had dared to explore the female form with an honesty few male artists could muster. But most women painters simply painted their female subjects clothed, in drawing rooms and gardens. Throughout art history women artists struggled for the same recognition as their male counterparts, but until the late 19th-century entry into art schools was denied and nude models unavailable to most of them.

During the last two decades of the 20th-century female art, students were avidly reading not only Lucie Irigary but other French feminists such as Julia Kristeva and Hélèn Cixous. Debates around socially constructed attitudes as to what it meant to be a woman – sexually, economically and intellectually – took centre stage. Feminist artists such as the Guerrilla Girls or Barbra Kruger tended to go down the conceptual route rather than expressing themselves in paint. What defined female beauty was also being deconstructed. Everyone had read John Berger’s Ways of Seeing and his analysis of the male’s gaze. Everything that, supposedly, defined what it meant to be a woman was being rethought through a feminist and mostly Marxist lens: our bodies, our sexuality, race and class.

In 1982 Susie Orbach wrote her seminal text Fat is a Feminist Issue

Following a path beaten through the jungles of patriarchy by predecessors such as Simone de Beauvoir and Germaine Greer. Orbach examined how the psychology of eating disorders such as bulimia and anorexia nervosa had little to do with greed, but rather more to do with women finding themselves caught up in a compulsive need to please, to create models of perfection. This was the time when we were led to believe that women could be femmes fatales in the bedroom, Hovis-toasting Mums in the kitchen and high-flying career women in the boardroom. Food became a means of nurture for when we fell short of this perfection, a way of filling the void that many felt but did not have the language to express. Too much food was how we both punished ourselves and healed what was wounded—feeling stressed? Can’t cope? Have another chocolate biscuit. Rather than speak of our pain, there was always another slice of hot buttered toast to be had, even if what we really wanted was self-esteem and love.

Saville spent several of her youthful summers in Venice. Her uncle showed her Titian’s Assumption of the Virgin, the altarpiece in the Friary. She was struck by its scale and dynamism which, she has since said, may well have had something to do with her own feelings about her size. She was excited by the possibility of ‘largeness’, the space it gave for her paint marks to travel both in a figurative and an abstract way. In Propped, the paint becomes flesh; at once beautiful, vulnerable, excessive and verging on the abject. It delivers a punch that is at one and the same time, psychological and physical. As a self-portrait, the work is revealing and brave, but it also has a raw vulnerability. Saville’s fingers scratch at the ample flesh of her thighs as if to draw blood, do harm and in, someway, punish herself. There’s self-hatred here, as well as self-confidence – all expressed through that most classical medium – paint.

Saville has said that painting and drawing are mediums in which she feels comfortable. That she likes the journey of making something that is ‘only itself’. Because it is not an algorithm, the same mark can never be made twice. Each one has to be felt in the mind and the body. There is always a tussle between form and space. Like Bacon, paint is used explore human emotion without resorting to standard academic techniques.

It’s interesting to note what has changed in the 20 years since Propped was painted. Certainly, the category of ‘woman’ has become more fluid and complex than it ever was when this was executed. However, Saville’s interrogation of what constitutes beauty still remains insightful, particularly in its mirroring of an ubiquitous cultural aversion to corpulence. One of her greatest achievements was to reclaim the female body from the male gaze, to paint the experience of being a woman from inside out, whilst using all the tools that she’d learnt from the masters, from Rubens to Rembrandt, from de Kooning to Freud, for her own ends.

Words: Sue Hubbard © Artlyst 2020 Photos Jenny Saville Propped 1992 Courtesy Sothebys

Sue Hubbard is a freelance art critic, novelist and award-winning poet.