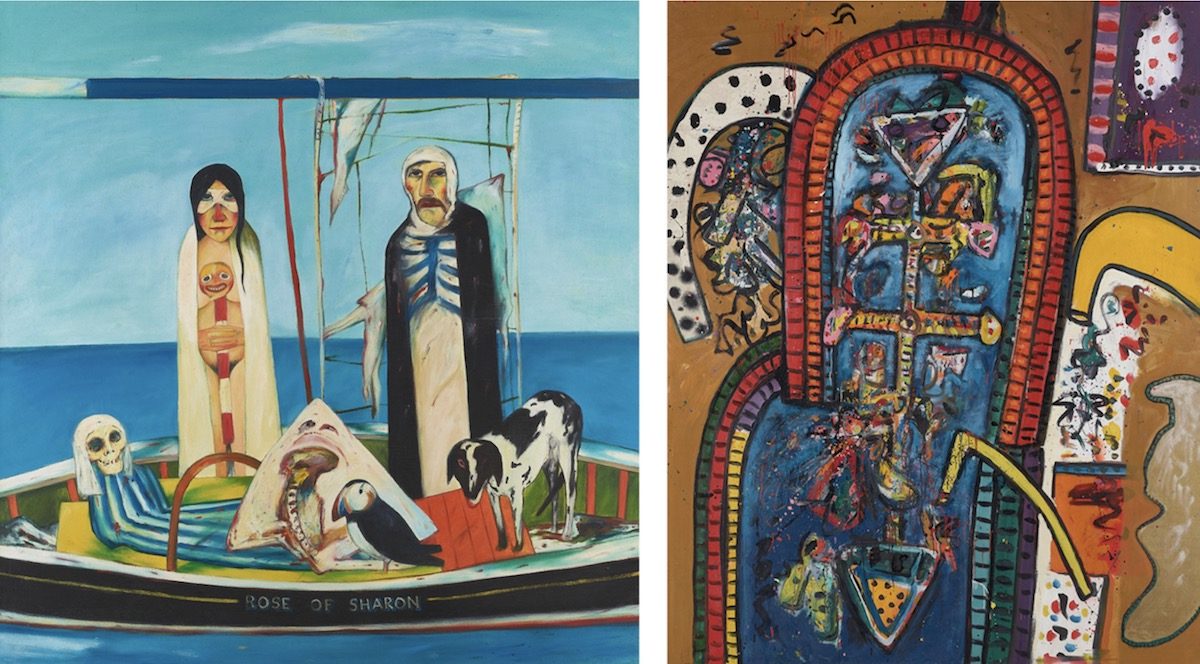

In 1983 John Bellany painted a double portrait depicting himself alongside Alan Davie. These two influential artists are Scotland’s best-known post-war artists. Cradle of Magic at Newport Street Gallery sets the work of each alongside the other and begins with a portrait of Davie by Bellany which hangs beside a self-portrait of Bellany from the time of his hospitalisation at Addenbrooke’s Hospital.

Davie, one of the first British artists to win international acclaim after World War II, was an influence on Bellany, Alisdair Gray, Craigie Aitchison, Christopher Wood and Lorraine G Huber. Bellany would later be a significant influence on the New Glasgow Boys, in particular, Peter Howson and Ken Currie.

Central themes such as love, addiction, passion, death and serenity are explored through a symbolic language

While their work differs, in that Davie’s work is primarily abstract deriving from use of automatism and Bellany’s mostly figurative and mythic, they share a significant point of connection in their love and purpose of Expressionism. Within Scottish art, the pair follow artists such as William McTaggart and William Johnstone through their interest in and use of Expressionism. Both achieve rich painterly effects through the excessive use of thick layers of oil paint. An abundance of black is used to amplify the brilliance of other colours and enhance the drama of works which surface our deepest emotions.

The work of Davie and Bellany also shares an interest in and engagement with religion; this being an interest shared, too, with some of those influenced by them. For Davie, this involves an interest in Zen Buddhism which derives, on the one hand, from the Beat Poets and their interest in eastern philosophies and, on the other, from the English orientalist Arthur Waley, mediated through his influence on Aldous Huxley and Bernard Leach. Helen Little suggests that: “As Waley described, Zen is principally concerned with things as they are without trying to interpret them, and is an attempt to understand the meaning of life resulting in total spontaneity and freedom without being misled by logical thought or language. As a result, Zen artists make images in a quick and evocative manner and are at one with their materials.”

Davie, himself, expressed similar thoughts in terms of the artist channelling spiritual joy and beauty. In a journal entry from 7 May 1948, written in Paris, we read: “Surely that spiritual joy which flows in us from the vision of a fine work [of art] comes not from a mere arrangement of material forms… surely the elusive quality of beauty is something which exists outside space and matter, in a world of timeless spirit, and the picture is only a materialisation of such spirit… a manifestation of spirit felt by a creative genius and passed to us through its conducting medium of form, as a wire can conduct electrical energy from one matter to another. The true essence of spiritual beauty is indestructible and everlasting.”

Steeped in Calvinism as a child by virtue of his birth at Port Seton in 1942 into a family of fishermen and boat builders, Bellany’s art has been described as “profoundly religious in its intimation of mortality and recognition of evil; facts reinforced in 1967 by a traumatic visit to the remains of the Buchenwald concentration camp.” Davie, together with the Scottish poet Hugh MacDiarmid, provided Bellany with the inspiration to attempt the creation of a specifically Scottish art drawing on these experiences and influences.

Central themes such as love, addiction, passion, death and serenity are explored through a symbolic language in which animals and humans merge and combine. The result is, as the artist Paul Huxley has said, that: “He has … a gusto for expressing emotional states. Everything comes out – nightmares, joy, exuberance … his art [has] a wonderfully, salty, gutsy character.”

Thom Cross has noted that “There is deep spirituality in his work that is profoundly moving, bringing to mind Highland psalms sung in that moving, plaintive style of the Gael.” Bellany himself said of his religious upbringing: “The deeper it goes in, the better for your soul – so everybody’s trying to plumb the depths. It’s taken as the most important thing in their whole existence and that moves into secular life as well. We’re not just talking about what happens in the church on Sunday but about a person’s behaviour on the other six days of the week. You don’t just turn it off like a tap. The depths you feel through religion for everyone in your life – it’s not a question of a surface recognition of vive la politesse. So the passions run very high.”

Energies and passions are what fuel the work of Davie and Bellany with their colours, strokes, shapes and images being the forms taken by the forces they unleash. The opulent plethora of shapes and signs combined with the intense iridescence of colour channelled by lead-lines of black that characterise Davie’s mature work are apparent through the Cradle of Magic exhibition, but never more expansively than in ‘Goddess of the Wheel’ and ‘Red Parrot Joy’. Davie’s lyrical brushwork and obsessive mark-making was the cradle in which “magical moments” were created “when he was completely surprised and ‘enraptured beyond knowing.'”

While Davie is at his best when his lines and strokes swirl and swoosh, Bellany is most effective when he works in lines. At the Newport Street Gallery, we see lines of gutted fish as understudies for ‘The Crucifixion’, a chamber-bound queue of Holocaust victims in ‘Pourquoi?’ and an accusatory line of sinister, shadowy Calvinists in ‘God is Love’. In Bellany’s case, the mark-making and brushstrokes become looser, more gestural and yet more serene, as he ages. It is in the earlier work that protests fashions his form and focus.

Ken Currie and Peter Howson were the New Glasgow Boys most influenced by Bellany, but it is Currie, in his later work, who has most closely shared Bellany’s fascination with the working lives and religious beliefs of Scotland’s fishing communities. For his most recent exhibition Red Ground, Currie created powerfully emotive equivalents in ‘Basking Shark’ and ‘Black Backed Gull’ to the gutted fish displayed in the manner of the crucifixion as depicted, for example, in Bellany’s ‘Allegory’ and in ‘Bird People (after JM)’ to the fisherfolk who feature in, for example, ‘Kinlochbervie’ or ‘Bethel’.

In ‘Black Backed Gull’ the gull’s splayed body recalls the archetypal image of the crucifixion while in ‘Basking Shark’ the shark’s coiling entrails relate to the tortuous ancient tradition of disembowelment, as recorded in accounts of the martyrdom of saints. ‘Bird People (After JM)’ portrays the controversial customary harvesting of gannet chicks by the Guga Hunters on the Hebridean island of Sula Sgeir, a tradition that has survived for generations in an area of Scotland that has been described as the last bastion of Calvinism in Britain.

This work, with its strong references to religious iconography and unflinching view of the suffering in contemporary society, constitutes a lifelong study into the fragility of the human condition. Currie depicts the damage inflicted by war and conflict, illness and decay as a response to what he feels is the sickness of contemporary society.

Violence is also a central theme in the work of Peter Howson but, as noted by Robert Heller, in ways that are “deeply influenced by apocalyptic thoughts and biblical references.” Throughout his career, Howson has interwoven themes of conflict and destruction, human suffering and redemption in his imaginative portrayals of contemporary society. Whether in Glasgow, Bosnia or elsewhere, homo homini lupus (man is wolf to man) is consistently demonstrated throughout the world and history he depicts. Howson stands with all those artists, such as Bosch, Goya, Dix and Rouault, who have sought to raise our gaze from the mire by painting the extent to which we are sinking in the mire. His more recent paintings on contemporary social and political themes have been founded on nightmarish visions of chaos and atrocity, portraying the universal suffering of humanity.

Howson is unusual among mainstream artists in his unashamed use of traditional religious iconography and application of a Trinitarian framework to his artistic practice. Although he does not shy away from the role that Christianity plays in his life and work, the religious overtures of his work are preceded by confession, as intimate details of his familial and spiritual relationships punctuate the parables of his imagination.

Howson has become an artist whose work is no longer viewed independently of his life. For much art, and for many artists, an attempt is made to view the artwork as an object in its own right with a life that is independent of the artist who made it. No such attempt is now made in Howson’s case, exhibitions such as A Life present work that offers “a visual journey of Howson’s altogether fascinating life, with works that are both extraordinary and intriguing.” Such exhibitions provide “the opportunity to become a direct witness to a diverse range of varying incidents and torments he has endured and encapsulated.”

His works now fit the chronology of his life: the dossers, boxers and misfits from the streets of Glasgow where he was raised, his battle with various addictions and personal demons, his work as a war artist, and his conversion to Christian faith. The theme of life’s struggles permeates his works, as indeed it does his life: “there’s a heroic strength in the works that lead one to admire not only him as a person but his ability to capture this through a medium that arrests and inspires you.” M Douglas Campbell writes that: “The God about whom and for whom he paints has transformed Peter. The images are alive because these biblical stories are not just characters in a book, but are part of the living Word; they are part of Peter’s life and world.”

Alan Davie spoke of “intense visionary powers, fears, fantasies and terrors of true knowing which is … nearer to God than man.” Mel Gooding ends his essay in the Cradle of Magic catalogue by arguing that there is in the work of both Davie and Bellany, “a darkness, a deeply ambivalent, ambiguous relation to the idea of birth and beginning, of sexuality and generation, of deaths and entrances” and “an enduring sense of wonder at the infinite arch of heaven, the radiant mysteries of the sun and moon, of light and space, the colour of sea and sky, the particularity and beauty of earthly things, the joys and terrors of human being.” Combining the forces of fear and wonder would seem to be the cradle of magic that characterises the visionary powers of these Scottish artists.

Words: Revd Jonathan Evens © Artlyst 2019 Photos: courtesy Newport Street Gallery

John Bellany and Alan Davie: Cradle of Magic, Newport Street Gallery until 1 September 2019