Pauline Sewards is a guest interviewer for Artlyst. In this enlightening interview, she speaks with writer, journalist, poet, musician and visual artist Jude Cowan Montague about her new graphic novel ‘Love on the Isle of Dogs’

Pauline Sewards: I love your book. It is beautifully produced by Friends of Alice Publishing. Can you describe the themes of the book.? It has been widely and positively reviewed. Have any of the reviewers noticed themes or details which you weren’t particularly aware of? Conversely have been surprised by any aspects which have not been commented on.

Jude Cowan Montague: I was a little scared putting this book together as it is about my personal life and the most traumatic part of my personal life that I kept hidden from my fun art circle for years. I kept it hidden because I didn’t want to remember the awful emotions and I didn’t want to muddy my happy, carefree life as an artist, exhibiting with my interesting and brilliant friends on the underground scene by recalling those difficult days. But when I was asked to contribute to a small exhibition about depression as I don’t usually get depressed, I thought I would go back to those frightening, impossible days.

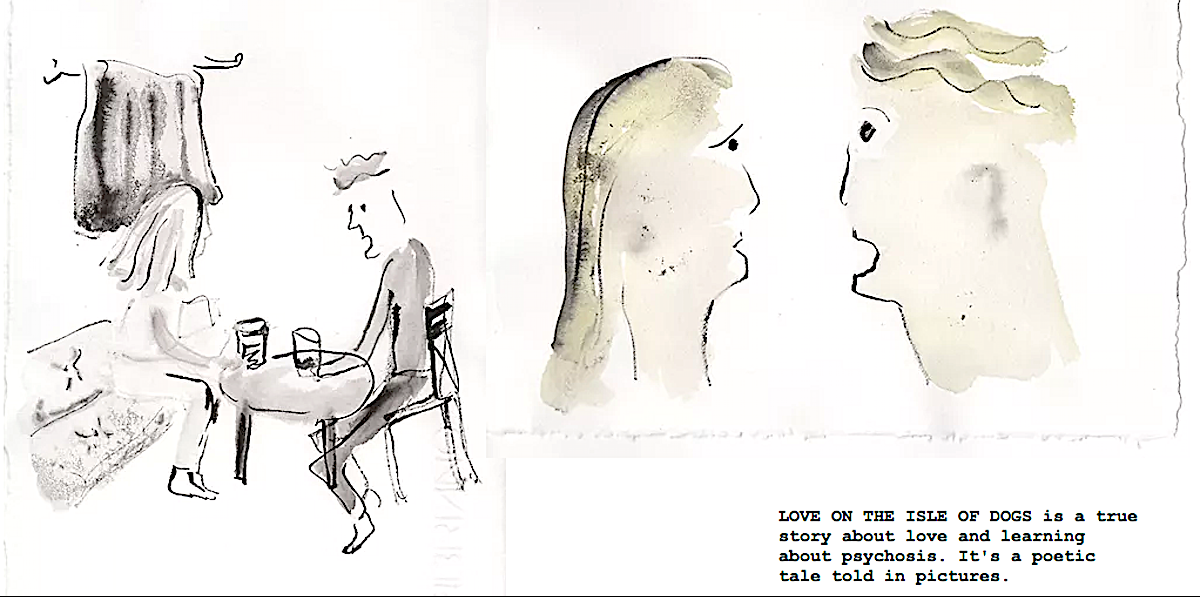

The book about my own life, about Love and about learning about psychosis. It’s about young motherhood, isolation and about shattered dreams and survival.

There is an underground theme running through the book of the Irish community in London. My Scottish Mancunian father lived in Belfast during the troubles and my husband was also from Northern Ireland. The relationship between Ireland the UK has been part of my life and here it is again, you can see it beneath the story of my marriage as if the pages were transparent.

There have been some wonderful reviews, it’s true, and they have startled me with their insight into my work. I thought perhaps people wouldn’t get it, because it is so personal – it’s my first graphic novel and it does not obey the ‘rules’, whatever rules they might be. It does not follow conventional comic format and I’ll talk a bit more about that shortly, so I had mixed expectations – I hoped it would communicate strongly, but I didn’t know if it would ‘work’.

My favourite review of all is in the Galway Literary Review by Matt Mooney. The poet Amy Barry put us in touch and I was absolutely blown away by the detail of his analysis. However, he concentrates on the text, whereas other reviews have responded more strongly to the ink drawings. I was relieved by the review in Broken Frontier by Rebecca Burke. Broken Frontier is an outstanding magazine specialising in reviewing graphic sequential art put together by Andy Oliver with a team of reviewers and writers, many of whom are themselves, graphic novelists or comic artists. I was thrilled by the philosophical references in her review – the summoning of the words of Jean-Paul Sartre, the comments about reconstruction of narrative. I think this is a beautiful sentence about the book: ‘ The truth is being bargained with and reconciled as Montague constantly questions what to show, what to leave out, what was real and what was perceived.’

Naturally, the subject that is of interest to most people is that of psychosis. It is often the element in the room in terms of stories of mental health. People are happier, it seems, to talk about depression or anxiety, but psychosis is more common than you would think from its visibility. It has been the subject of many films and many books. I drew some of the ones that had been apparent to me as I grew up, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath. In these narratives, it is the experience of the patient with whom the reader must and should identify with. But in mine, I break the usual focus and show psychosis through the lens of the carer, the carer who has to abandon the sufferer. It is somewhat of a taboo. I was nervous to show it. But as soon as the stories of the readers came tumbling out, their desire to share their own experiences, I knew I had done something powerful and important. As an artist, this is an ambition realised. But it is a bitter-sweet knowledge that this has been achieved through my making visible own personal tragedy.

PS: Jude, I first knew you as a poet and musician but became aware that you have lots of strands to your creativity. Can you tell me a bit about your training and development as a visual artist?

JCM: Pauline, what wonderful, exciting days in East London, performing at venues, open mics, poetry readings together. We both remember the MC Jazzman John, who supported both of us and many others.

I remember always wanting to be a visual artist. As a child, I spent every Saturday with my grandfather, who I admired terribly. He was a professional musician, but we would draw together. We would draw houses and fields, walls and skies, trees and flowers. His house looked like a time capsule from the 1920s. He was so stylish. He was a huge influence on me, but I also felt inelegant, clumsy and ugly in my movements and in my sketches. My line was too modern. I wanted to be an older generation of artist, an artist like him, but which was completely unfashionable for my generation.

When I went to college in Oxford to study English, I took up fine art printmaking. The tutor was Jean Lodge who worked at Atelier 17 with Stanley Hayter. She was a huge influence on me with her ideas about experimentation with woodcut and other media. Yet it took me many years to go back to fine art printmaking. I finally went to Camberwell College of Arts and took up etching once more. And loved it.

My printmaking owes a great deal to the surrealistic poster art from Central Europe for cinema posters.

I am hugely influenced by illustration, book illustration, more so than by many painters and while this is fashionable now, I have often felt it to be considered a poor relation of fine art.

PS: Which came first – your interest in visual art, music or writing or have they always co-existed?

They have always co-existed but have been separate strands. Perhaps more recently they are coming to knot together – but I don’t know, they are always shifting for me.

PS: Could you tell me more about the structure of the book? It is very unusual, possibly unique to have a graphic novel followed by a prose account of the same events. As a reader, I found this innovation very satisfying. The written account allowed me to peep behind the scenes in the pictures and learn and reflect more, although each part of the book could stand alone. Following on from this, could you also talk about the process of putting the book together. Did you plan this structure from the outset? I believe you have said that you completed the artwork before writing the second section and it would be good to hear more about this.

JCM: This structure, that I have never seen before, emerged by accident during the process. I began with drawing memories. As I said earlier, creating visual work for a joint exhibition was the initial trigger for beginning this project. The exhibition was called ‘A Small Exhibition about Depression’ and was in Beverley Isaac’s toilet, which she amusingly called The Louvre. Also showing was the artist Julia Maddison. The response to my work encouraged me to turn the few pictures into an entire pictorial narrative.

Emily Haworth-Booth, an award-winning graphic storyteller and teacher at the Royal Drawing School, gave me a positive critique of the work in her evening class and this gave me the confidence to complete it. I exhibited it a few times while in progress, including at hARTslane experimental art venue in SE London, and I felt it was becoming a rounded and well-organised piece of work.

The author Sally Bayley asked me to lead a workshop at the Relit school in Oxford about drawing from memory and then asked me if I might consider creating a text about the story too. I was at first reluctant as I felt the drawings told the whole emotional story. But as I have a huge respect for Sally who wrote the amazing book ‘Girl With Dove’ (which I adore) I decided to try. When I was on a residency at the Writers’ and Translators’ House in Ventspils in April 2019, I wrote the basis of what became the text in the book today. I wanted it to be longer, but 20,000 words felt right, so I stopped there.

I wanted to integrate the words and the text, but it didn’t seem to work. When I had the idea to put the pictures first and the text second so people could read the pictures, then the text then return to read the pictures informed by the text it was like a flash of lightning, a Eureka moment. It wasn’t a make-do solution. It felt like a bold piece of narrative engineering. And it has worked, according to the feedback. It works.

PS: Did you storyboard the graphic memoir first and did you write chronologically? The drawings seem fresh and alive as if the ink isn’t quite dry on the page in places. You have a way of depicting movement as if it is happening in real-time. How much editing did you actually need to do?

I did not work chronologically. I drew the scenes that were strong in my head. I drew them and I tried to feel them. I needed the pictures to retain the emotion. This was my paramount concern. The feeling needed to be strong. I needed to feel it while I made the picture and when I looked at the picture. This was hard. I did a little each day. In the end, I joined them up as best I could and added text and extra pictures for clarity and to establish place, time and character.

PS: As others have commented, the drawings depict psychic states, for me, one of the key images could be interpreted as showing the black dog of depression with the couple at the heart of the story.

JCM: Yes, thank you so much, but that little black dog’s story mirrored the story with my husband. I loved that black dog but could not keep it as it was destructive when left alone. It ripped up everything and had special powers so it could jump over walls, six-foot walls, an incredible spring-legged lurcher. I couldn’t keep the dog. I couldn’t keep my husband even though I loved them both. Love had become impossible.

PS: One of the main themes of the book is domestic violence. You place this in the context of mental illness and the lack of support available at a time when services were moving out from hospital and institutions and into the community. The images which depict the emotional distress and physical violence are visceral and draw the reader in. Can you say more about the process of producing these images.

JCM: Ah . . . such a hard subject but one that it is so important. Yes, at the time, I was so confused by what treatment was and meant, yet I became aware quite quickly of the political background to the care situation in which I was immersed. It was the onset of Community Care policy. The criticism of institutional care, the valid, heartfelt criticism which looked at how many people, and women, in particular, had been abandoned for lifetimes ‘inside’, even people with no real symptoms that would lead to a diagnosis was used to power a new generation of care in the community. What this meant for those in my position, what I realised was that I would be the care in the community. I couldn’t do this. I wasn’t able to do this. As a young mother, I was vulnerable myself. I had to be brought to realise that I couldn’t be this person as that road would lead to a real tragedy. I had to be hard. That wasn’t easy for me.

Some of the images depict the health service at this time and how I began to realise how things worked.

Other images are more personal. I always let the emotional memory speak, so the pictures naturally took on a character of making that reflected the emotional content. Spare pictures for a more meditative calm moment. Crazy jagged lines for nightmare content. Figures from the art movement of expressionism sit alongside my work. Munch and Chagall are two artists who people often reference in looking at my work. One known for agony, one for romantic softness. These areas fuse in LoveLove on the Isle of Dogs.

PS: I find that reading a graphic novel is a bit like watching a film. Have you got an interest in film and storytelling? Interestingly, you have included text in many of the pictures.

JCM: Yes, I love film, but this is definitely not a storyboard. My particular interest as a film historian and archivist (I trained and worked in these areas) is in early actuality film. Short actualities of people working, walking, doing, filmed from afar. But perhaps the work could be said to echo the expressionist feature films like The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (Germany, 1920) or Waxworks (1924). I am a huge fan of the director Fritz Lang, who isn’t?

PS: Can you say a bit about your next project?

JCM: I am working on the sequel to LoveLove which I’m calling Breakfast in Shoreditch. The title is a nod to Breakfast at Tiffany’s, the film more than the book, the carefree picture of a girl re-finding herself in the party scene of the city after her young life had been taken away from responsibilities. There are themes of the power of aesthetics and letting yourself go in order to get away from inner troubles. The central character is a victim of trauma and is having some inner trouble readjusting to being free to be responsible for only herself. She is also using enjoyment and the rough-and-tumble of party-city-life to do this. I felt definite echoes in this part of my life story.

The book is about a short summer of absent motherhood in which my French friend re-taught me to have fun, be playful and be wild. How to enjoy clothes again. How to feel it is okay to stand outside the responsibilities that had been thrust upon me. How to be myself before my daughter returned to me and we became a single-parent family, once more the two of us.

PS: I’m aware that you have been interviewing artists as part of this series. Can you say more about the artists who have influenced you?

JCM: Yes, I am hugely influenced by the cartoonist John Glashan. I love humour. I identify with his Scottish dourness and his laconic lines, his social straddling, one foot in a bucket of meths and the other in the bidet of a stately castle. He loves materials, their juicy, sticky, spreading glory, the tackiness of hardboard and the gloop of a dark evening in the murk.

PS: During the research for this interview, I came across a trailer for the book with some wonderful music which casts a new emotional dimension on the project. Is this something you can envisage taking further? Could you say a bit more about the ‘Her Indoors’ collaboration which you collated earlier this year and is available on Bandcamp?

JCM: Ah, yes, the trailer adds a musical quality that adds a more theatrical element to the story. I am a keen consumer of Giallo music. I love the Hammond Organ and real, vintage music-making organs of the 1960s and 1970s. Powerful vintage keyboards are part of my music-making and with Matt Armstrong, I produced the album Hammond Hits which has been so well-received (it’s available from Norman Records). For the trailer, I knotted together some musical guitar sounds I created for another project together with some words made more impressive via the use of vintage effects and felt my way instinctively through a short collage. The inspiration is no doubt very Giallo, using beautiful (to me) and forboding sounds made by the great circuitry of the 1960s and 1970s which seems no longer possible – is that because the components manufactured today are different? Was there a build quality due to the engineers and manufacturers of yore that created sound that is no longer there? I suspect so but would be great if there were more research on this.

Her Indoors was a compilation album with almost 50 artists that was released on Bandcamp this year. Women were invited to contribute tracks to fundraise for charity against domestic violence. For the cover I used afoot, a barefoot, walking on eggshells. It’s a classic image and one with which so many of us can identify in so many different situations. It’s an image from LoveLove on the Isle of Dogs.

PS: I also wanted to ask about your visual influences artists you like and other graphic work you like and maybe autobiographical work you like.

JCM: In the autobiography, I was influenced by the work of my writer friend Sally Bayley. I recommend her memoir, ‘Girl with Dove: A Life Built by Books’. It is the story of her chaotic childhood but told through the help of books that pulled her through it, her friends from the pages, like Jane Eyre and Miss Marple. I was influenced by how you can tell an emotional story that at the time you do not understand by putting on spectacles that look sideways and peer into your former mind.

PS: Finally – thank you for discussing the book with me, Jude. I feel very privileged to learn about the creative processes which brought it together and I can probably ask another dozen questions too!

Love on the Isle of Dogs available from The Book Depository

Pauline Sewards is a guest interviewer for Artlyst: she has recently published a second collection of poetry Spirograph though Burning Eye Books. The collection looks at change and personal history, and it is influenced by her work as a mental health nurse. The cover of the book was designed by her son Aaron Sewards, whose miniature watercolours have recently featured in an exhibition in Kurobe, Toyama Prefecture, Japan. Jude and Pauline recently discussed their books on Jude’s weekly Resonance FM show ‘The Newsagents’.