What makes a Significant Work? Not necessarily what is fashionable or new but an artwork that holds its own down the years, that continues to resonate and still has something to say. It seems extraordinary that I first saw Mona Hatoum’s installation The Light at the End at The Showroom in East London in 1989. I was a young critic and fairly new to London and it quite literally stopped me in my tracks. This is what I wanted from art.

Mona Hatoum knits together the ethical and aesthetic tensions of the exile – SH

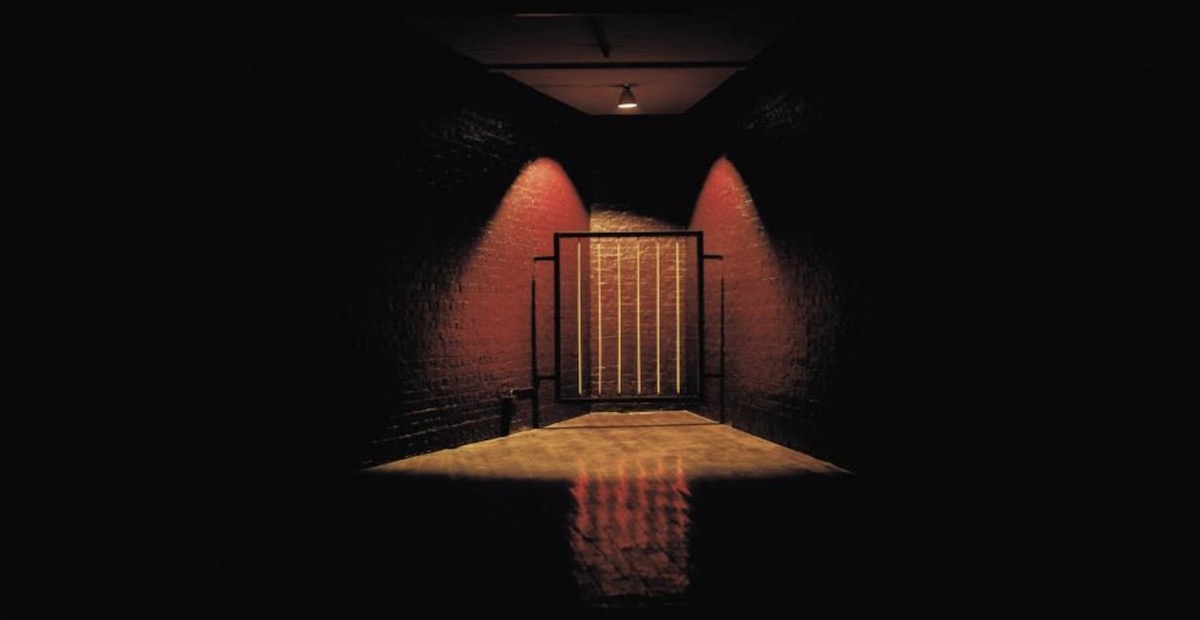

Here was a work made from the most minimal of non-art materials turned into a gut-wrenching metaphor. In the darkened industrialised space where the brick walls had been painted ox-blood red, an angle-iron frame and six vertical electric heating elements glowed in the darkness to form a gate at the end of the narrowing space that blocked off the corner of the room like a cell. Drawn towards the intense orange lines, the work seemed to offer both promise and danger as light gave way to heat and I was greeted by the glowing red-hot grill. The sublime grids of Agnes Martin, the emotional installations of Eva Hesse and the mythic works of Joseph Beuys all seemed to coalesce here, while the human scale provoked uncomfortable thoughts of torture and incarceration.

Born in Beirut in 1952 to a Palestinian family living in Haifa, Mona Hatoum settled in London in 1975, after war broke out in the Lebanon. This was a Britain that was seeing swift cultural change and widespread industrial action. The ‘Winter of Discontent’ under a Labour government was about to give way to the election of Thatcher in 1979. It was during Hatoum’s time as a student at the Slade School of Art that she began to submerge herself in feminist and political debate, in the counter-cultural discourses surrounding gender, identity and race that were being hotly debated by influential thinkers such as Edward Said in key texts like Orientalism (1978).

Even if I hadn’t known that Mona Hatoum was a Palestinian living in exile, the sense of menace and entrapment were palpable. But the work’s power was not that it was descriptive, but that it was ahistorical and attached not to a singular moment but spoke of all inhumanity from the Spanish Inquisition, through to the disasters in Syria. Here was a metaphor for political violence that carried a title ironically suggesting hope. The work pre-dates the abuse of detainees in Abu Ghraib under George W. Bush’s administration but now seems prescient of what was to come: the aggravated assaults, the electric shocks, the harsh and inhumane treatment of detainees. Hunkered in the corner of the space, its rectangular presence could be read as a secular altarpiece erected to pain and injustice. Death and hope, as in much great Christian art, are close bedfellows and the work conjures Rilke’s famous lines “for beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror which we are barely able to endure.”

For the viewer, the malevolent and the sublime, the abstract, the uncanny and the concrete all meld into an uncomfortable confusion. What are we supposed to feel? Fear, awe, excitement? And how can we get out of our heads the subliminal suggestion of internment camps or the cheap, unsafe accommodation endured by so many itinerant workers? Containing a play between the dark and the secret, the luminous and the redemptive associations of religious art, the work is closely rooted in contemporary culture. Mona Hatoum knits together the ethical and aesthetic tensions of the exile and the outsider to ask a series of open-ended questions.

Despite early experience of displacement, this is not an artwork with an autobiographical message but rather one concerned with issues and discussions of modernity. Both political and critical, it displays an awareness of the history of art, from the medieval altarpieces of great European churches to the sensory perception of arte povera and its use of adapted, often scavenged materials. Her theatrical iconography – elsewhere she uses cages, lightbulbs, iron bedsteads and even hair – challenges the viewer, wrong-footing them when they fall too easily into cliched interpretations. Her categories are constantly shifting. The body and psychology, the spiritual and the corporeal, are juxtaposed to create a poetic yet loosely political commentary on today’s crisis-ridden world. Made from the stuff of life, the stuff of the everyday – wire, wood, metal, light bulbs – Mona Hatoum creates a wholly contemporary, highly expressive grammar. Now, more than thirty years on, The Light at the End seems just as relevant, pertinent to the cultural debates around postcolonialism and postminimalism. In a world of flux and contradiction, with the rise of geopolitical tensions and the possible re-emergence of the cold war, this hard-hitting work forces us away from the chirpy irony and easy, ever-so-clever kitsch of the late 20th and early 21st-century art world’ into a realm of the turbulent, the authentic and the challenging. It is a reminder that art has a duty not to be just entertainment or an object for investment but to challenge, inform and make us think. Hard to bear, it reminds us of those who continue to be displaced, who suffer exile and deprivation. Offering little respite, it presents us, instead, with a poetry of sorrow and loss, forcing us to face the dark narratives of our turbulent and compromised epoch.

Sue Hubbard is an award-winning poet, novelist and freelance art critic.