In an era when modernism was dictating that painting should abandon all connection to narrative, Paula Rego defiantly continued to tell stories, influenced by the Portuguese folk and fairy tales of her childhood. Born in Lisbon in 1935, she grew up under the jackboot of the fascist dictator António de Oliveria Salazar, who seized power in 1926 after a military coup, as Europe slowly slid towards the right. Although her father was liberal and anti-clerical, the febrile atmosphere of the surrounding conservative society created a profound anxiety in her as a child, causing her to withdraw into art as a way of making sense of and reimagining a world where she perceived that women had little voice and even less agency.

Every woman adores a Fascist,

The boot in the face, the brute

Brute heart of a brute like you.

– Sylvia Plath, Daddy.

With their biomorphic shapes and Disneyesque figures, her early works show the influence of Surrealists such as Miro, along with the violent graphics of popular Portuguese comics, and feed into her ferocious sense of irony. Later, while living in London, Rego would take on Portugal’s political establishment and, in particular, its treatment of women. This reached its acme after the failure of the referendum to legalise abortion, in her searing landmark series painted between 1997-98. Here, women wracked with pain crouch on chamber pots and over plastic buckets or lie traumatised on their beds. As in most of Rego’s work, the idealised female of art history gives way to a lived, sentient reality. These are not the draped muses of the European canon offered for the male gaze but women with solid thighs and arms who bear children, cook and scrub floors, working women with their own sexual longings, vulnerabilities, subterranean angers and strengths.

Choosing one painting for this series, out of so many powerful works, was hard, but The Policeman’s Daughter 1987 seems to sum up Rego’s iconoclastic storytelling, her ability to create powerful psychological dramas and mise-en-scènes. A girl in a white dress with muscular arms and a grim chiselled face, one foot curled beneath her on a wooden dining chair, the other shod in a child’s white buttoned sandal balancing her sturdy body against the floor, thrusts her thick arm into a big black riding boot, which she’s busy polishing. The title tells us that she is a policeman’s daughter, so, by implication, the boot belongs to her father. A black jackboot, an emblem of machismo authority, her arm has slipped inside almost to her armpit. With its stark colours, it hard shadows and almost monochromatic palette, the painting suggests a disturbing sexual inversion, a perverse act of penetration, a symbol of deflowering, even rape. There’s the uneasy sense of taboo sexual practices, of domestic abuse and yet…. who, here, really has the power?

In his 1933 analysis of Fascism, Wilhelm Reich wrote: “the sexual effect of a uniform, the erotically provocative effect of rhythmically goose-stepping, the exhibitionist nature of militaristic procedures, have been more practically comprehended by a salesgirl or an average secretary than by our most erudite politicians”. Reich showed Fascism to be an extremely libidinal form of politics – theatrical, mesmerising, seductive and sadomasochistic – in its appeal to its female adherents. Sexual bondage and a yearning for domination permeates its imagery. Men of power from every political creed have made use of their authority for sexual favours (Stalin and Mao both enjoyed a harem of women). Still, Fascism was peculiar in the submissive adoration it inculcated in its female adherents. At its heart is a fascination with cruelty. The cruelty of socialism sends millions to their deaths in the deluded hope of engineering a new utopia. Still, the cruelty of the fascist is unashamedly machismo with its need to assert supremacy and control. As Aldous Huxley noted in his foreword to Brave New World: “As political and economic freedom diminishes, sexual freedom tends to compensate to increase.” Sexual and political domination, it seems, go hand in hand.

Having spent more than 40 years in Jungian analysis, Paula Rego is wholly aware of the subversive symbolism she brings to her work. Yet, unlike Balthus’s images of pre-pubescent girls, her work is never voyeuristic or titillating. Not afraid to shock, she is never prurient but rather evokes our empathy and compassion. We, the viewer, do not gawp or gaze but identify with her subjects in all their multifaceted vulnerability and sneaky nastiness, their iconoclastic gleefulness at breaking free and subverting accepted norms. The sensual polishing of the father’s boot in The Policeman’s daughter suggests the forbidden delights of adolescent masturbation, the young girl dreaming of the handsome uniformed men who will dominate her as she pleasures herself. A black cat on the right of the picture standing on its hind legs conjures the slang word ‘pussy’ or the French ‘la chatte’, further adding a layer of sexual inuendo.

Allusive, multi-layered and enigmatic, nothing in Rego’s world is quite what it seems. Like the regulated religious Portuguese society in which she grew up, there’s what happens on the surface and there is what goes on behind lace curtains. The policeman’s daughter sits with her back to the window open onto a dark velvety night and the freedom it offers away from the claustrophobic constraints of the family. Yet, despite its allure, she goes on polishing. The sacrificial virgin is juxtaposed here with the authoritarian jackboot of Fascism, “the black shoe” to quote Sylvia Plath, “In which I have lived like a foot/For thirty years, poor and white,/Barely daring to breathe or Achoo.”

Despite these constraints, Rego’s girls and women are not victims but find ways to defy the sinister side of sexuality and family relationships. The Policeman’s Daughter isn’t cowered but defiant. By discovering her own sexual power, she gives voice to her simmering anger and sense of isolation, surreptitiously exacting revenge against a society that would keep her as a symbol of purity in her white dress, a virgin rather than a sexually knowing woman or a whore.

Visit Paula Rego At Tate Britain

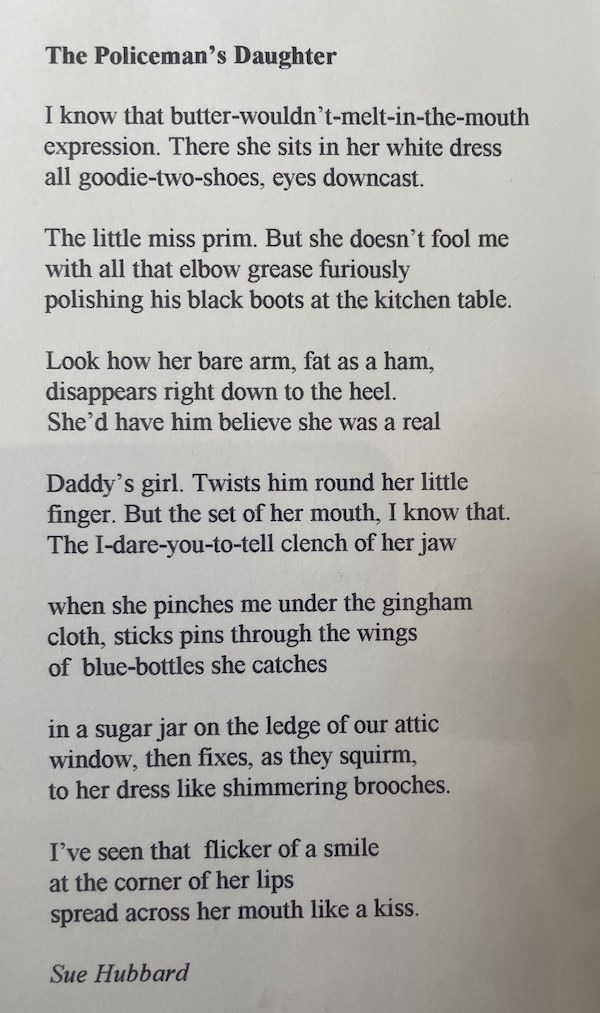

Sue Hubbard is an award-winning poet, novelist and art critic. Her latest novel Rainsongs is published by Duckworth. Her fourth poetry collection, Swimming to Albania, is due from Salmon Press this autumn.