Art Out of the Bloodlands: A Century of Polish Artists in Britain at the Ben Uri Gallery focuses on the contribution made by the largest migrant community to 20th/21st Century British Art by highlighting the work of Polish artists who have worked and continue to work in Britain. Featured artists include Jankel Adler, Janina Baranowska, Marian Bohusz-Szyszko, Stanislaw Frenkiel, Feliks Topolski and Alfred Wolmark, complemented by contemporary practitioners working in London now. All but a handful of the featured works have been created in England – the new homeland – yet many retain symbols of Polish national identity, from Catholicism and the cavalry to the dark forests and traditional embroidery.

There is a fascinating story that remains to be fully told about the European artists who fled to Britain from Nazi or Soviet persecution

There is a fascinating story that remains to be fully told about the European artists who fled to Britain from Nazi or Soviet persecution and their reception in England. Douglas Hall, who wrote Art in Exile the first substantial study of the artists featured in the exhibition, thinks there remains the need to rouse the art establishment in the UK to a proper appreciation of the value of artists of foreign origin that have been in their midst. Hall sees this group of Polish artists as having experienced a double exile, as they found that they did not ‘conform to the norms laid down … by the nexus of opinion-formers who control the means of promotion, reward, and publicity in the art world,’ yet also were cut-off from ‘a European culture more emotionally generous, more learned and more concerned with meaning than the one they found here.’[i]

Despite this émigré artists did, sometimes with support from British churches, build significant careers. The German Jew Hans Feibusch, for example, became one of the principal muralists of his generation, the Hungarian Ervin Bossanyi was a well-regarded maker of stained glass and the ceramic works of the Pole Adam Kossowski can be found in Roman Catholic churches throughout the land. Exile and rejection are themes with deep biblical roots and as significant numbers of Polish artists, in reaction and response, have been influenced by Roman Catholicism; it comes as no surprise to find such themes among their work and featuring in this exhibition. Bohusz-Szyszko and other exiled Polish artists such as Baranowska, Frenkiel, Kossowski, Henryk Gotlib, Marek Zulawski, and Aleksander Zyw were part of a consistent but under-recognised strand of artists’ employing sacred themes which runs throughout the 20th century in the UK. The exhibition provides an opportunity to review the reputations of two Expressionist masters from this group of Polish émigré artists; Bohusz-Szyszko and Frenkiel.

Bohusz-Szysko’s is a story which deserves retelling as his work retains its mystical power and vision and his contribution to the image and reality of hospices as landscaped, art-filled, home-like havens remains a significant contribution to have made, not just to art but also to healthcare. Despite this, Hall notes that sadly ‘it seems that Bohusz’s religious visions did blind the art world of his time to the extraordinary quality of his work.’

Bohusz-Szyszko had been teaching Polish servicemen in Rome to paint prior to his arrival in Britain in 1947. Hall writes: “Bohusz-Szyszko immediately set about creating the conditions in which he could continue his teaching mission, at first in a reception camp, later at various addresses in London and finally at the St Christopher Hospice at Sydenham. The classes became known as the Polish School of Painting, and were eventually taken under the wing of The Polish University Abroad. The relatively younger artists, including Frenkiel, founded in 1948 the Young Artists Association … A group calling themselves Group 49 took its place a year later and mainly consisted of pupils of Bohusz-Szyszko … In 1955, with Polish artists beginning to be more successful commercially, a society was formed with the neutral title of The Association of Polish Artists in Great Britain (APA) … Although APA was intended to be a broad church, the pupils of Marian Bohusz were still the most important element. The spiritual intensity of Bohusz’s work … was almost impossible to pass on to others, and without it the overall impression of APA is of a conservative body whose members had little desire to rock any boats. Gotlib and [Zdzislaw] Ruszkowski were early members, but dropped out. Frenkiel stayed the course and was for a time Secretary; his work, unique in any context, stands out even more sharply in this one.”

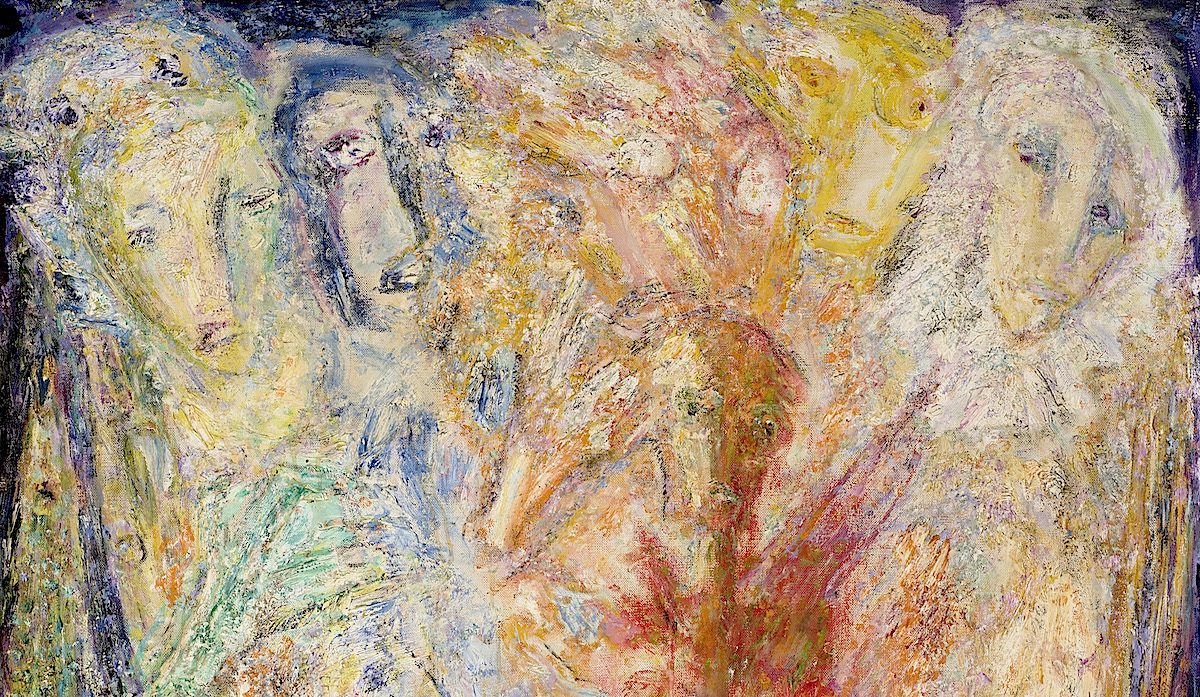

From the first, Bohusz-Szyszko had been a religious artist. In 1939 Professor Tadeusz Pruszkowski noted, in a review of Bohusz’s first one man exhibition, that he had ‘not set himself an easy task in introducing into the tradition of religious art the achievements of the modern approach to colour.’ Bohusz searched for transcendence through a time consuming process of painting and over painting which enabled his figures to be illuminated from the paint structure itself rather than an external source of light. His devotional bounty of paint with its bold singing colours created a spiritually intense ecstatic vision that is all joy and hope, even when painting death.

As Jan Wiktor Sienkiewicz has written: ‘In Marian Bohusz-Szyszko’s paintings Christ is always stretched on a leaning cross (along with the diagonal line of the painting), hung in a whirling and heavy atmosphere of dark sapphire heaven, often with a bright “window” in the background. For Bohusz each Crucifixion foreshadows Resurrection. In a moment Christ is going to appear among the people!’[ii]

Hall notes that ‘Bohusz-Szyszko, the Catholic, found release in a search for transcendence, which he achieved with a devotional bounty of paint parallel, only, to Expressionism.’ The Rt Revd Dr John V. Taylor, who championed and purchased Bohusz-Szyszko’s work while General Secretary to the Church Mission Society and Bishop of Winchester, described him as ‘a profoundly spiritual painter,’ ‘a supreme colourist’ and a mystic whose paintings ‘are, in a sense, icons which call for contemplation.’ Noting the tactile pleasure of the way Bohusz-Szyszko applied paint to canvas, Taylor stated that his ‘is the art of a materialist who understands the divinity of matter in the manner of a mystic.’[iii] This aspect of Bohusz-Szyszko’s work is represented in Art Out of the Bloodlands by ‘Birth of Man’ where the feverish frenzy of his mark-making results in flame-like brushstrokes evoking the primal energies of creation. Bohusz-Szyszko’s work can principally be found at St Christopher’s Hospice in Sydenham, where he became artist-in-residence following a chance encounter with Doctor Cicely Saunders, who he later married.

Stanislaw Frenkiel’s art moved in the opposite direction to the transcendent mysticism of Bohusz-Szyszko as he took ‘the exposure of human foolishness, self-indulgence, and dissoluteness to the point of ruthlessness’. In making this statement Anthony Dyson notes that Frenkiel ‘is equally ruthless with himself in exposing his own weaknesses.’[iv] Hall notes that Frenkiel met Georges Rouault in Paris and was influenced by his ‘earlier works in watercolour and graphic media’ from which he learned ‘the religious significance’:

‘of … outcasts of society, the abused as well as their abusers, whom Rouault portrayed with equal ruthlessness as if equally corrupted in the flesh, but all holding out the possibility of redemption and regeneration. The lesson was not lost on the young man with a well-developed knowledge of the flesh and the consequences of its vulnerability. The sense of the dual nature of fleshly existence remained with him always, and was the driving force behind his mature work.’

‘What Anthony Dyson calls “Frenkiel’s essential preoccupation with making the ordinary extraordinary” had been with him almost from the beginning.’ ‘Lawrence Bradshaw assessed Frenkiel … as “an actor-producer, who invents his own dramas, selects his own cast and creates his own happenings”.’‘All his work is imbued with the concept of original sin and redemption’: ‘As a Roman Catholic, he realised that the central mystery of his faith was God’s will to re-unite divided humanity by the act of redemption … For Frenkiel the sinful part of humanity had a positive value; being a sinner himself, he took comfort in the belief that Catholicism was the religion of sinners. ‘In order to be forgiven, you have to sin,’ as he once unguardedly put it. He often made use of expressions like ‘the spirituality of sensory experience’ or ‘the legitimacy of desire’. He had no time for the Protestant fear of contamination, comparing it to an artist’s not wanting to get his hands dirty, whereas he himself revelled in the sensual satisfaction of handling paint and being ‘contaminated’ by it. All this is the background both to Frenkiel’s unconstrained Expressionism and his joyful and not so joyful depictions of erring humanity … His views were not a smokescreen for voyeurism as a cynic might suggest. ‘The crux of all that I have been trying to do is to find some kind of saving element in disgrace,’ he told Dyson.’

Throughout his career, as Dyson notes, he ‘has continued to tap that vein of expressiveness which so early in life he discerned and admired in the work of his heroes: Goya, Ensor, Rouault and their like.’ In Art Out of the Bloodlands, this central element of Frenkiel’s work is represented by one from his series of Incantations paintings, a scene of licentiousness within which a priest and a variety of spiritual symbols are depicted. Dyson remarks of this series that it is as if ‘the mysteriousness of the subject is insufficient in itself, the bizarre assembly of incongruously-matched personages compounds the puzzlement.’

It is only when we turn to Christ in Frenkiel’s work that we find a counterpoise to this ruthless exposure of abuse. Christ Mocked by Soldiers is the supreme example of the poignant paradox, in which Frenkiel actually believes most deeply, of Christ, as Fool, ‘setting aside the human instinct for self-preservation and surrendering meekly to his tormentors’ in order thereby to appear most human, regal and divine.

Bohusz-Szyszko and Frenkiel use expressionism to different ends – transcendence and fallenness, mysticism and realism – yet it is the evident faith of both which drives and inspires them in their differing visions, which are, ultimately, two halves of one whole; that whole being an art born from the bloodland of Christ’s crucifixion.

Words By Revd Jonathan Evens Priest-in-charge St Stephen Walbrook London Top Image “Birth of Man’ by Marian Bohusz-Szyszko Photo: by Justin Piperger reproduced with permission of St Christopher’s Hospice’.

Art Out of the Bloodlands: A Century of Polish Artists in Britain Exhibition dates: 28 June – 17 September 2017 Ben Uri, 108a Boundary Road, off Abbey Road, St John’s Wood, London NW8 0RH Visit Here

[i] Art in Exile (D. Hall, Sansom & Company Ltd, 2008) [ii] Wojciech Falkowski: Painting (Jan Wiktor Sienkiewicz, Lublin 2005) [iii] Marian Bohusz (M. Wykes-Joyce, Drian Gallery, 1977) [iv] Passion & Paradox: The Art of Stanislaw Frenkiel (A. Dyson, Black Star Press, 2001)