In Grove Road, Mile End, there’s a plaque on the north side of the railway bridge that commemorates the first flying bomb to fall on London on 13th June 1944, a week after D-Day. The VI bomb-damaged houses in Antil Road, Burnside Street and Bellraven Street and destroyed the train line from Liverpool Street to Stratford, killing 6 people and injuring 42. A local recalled that they were all sworn to secrecy but that “the news got out soon enough”. The plague was put up in Grove Road by the Greater London Council in 1985 following the proposal of Joseph V Waters, a lifelong Easter Ender, whose brothers had been injured by the bomb.

As late as 1993, some of the terraced houses in Grove Road that had survived were still standing

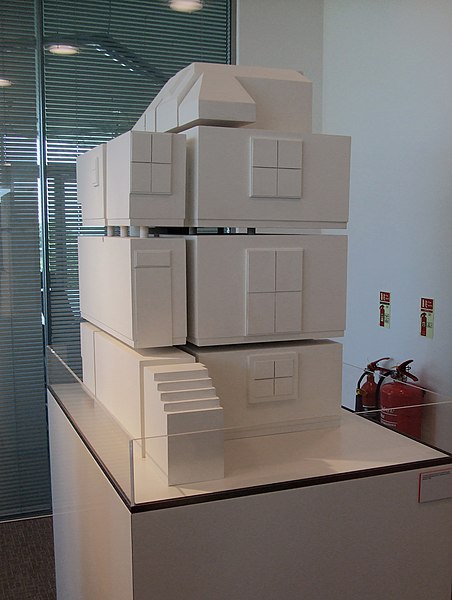

Rachel Whiteread, then a thirty-year-old artist with a growing reputation, approached the last tenant, retired docker Sydney Gale, who’d lived at 193, to explain her desire to make an artwork out of his old home before it was demolished to create Wennington Green ‘part of a grand scheme to form green corridors connecting the heart of London to the suburbs.’ With the help of the public art organisation, Artangel, a temporary lease was obtained for the plot. Inside 193 held a wealth of treasures: cast iron fire grates, original mouldings, old light switches and wooden cupboards. The house was used as a mould and filled with concrete to create an imprint of the building before the outer structure was finally removed. It was an audacious and brilliant idea. Part mausoleum, part memorial to a lost way of life that captured the vanished rhythms and resonances of a dying East End community, its hidden histories, preserving them like flies in amber.

The piece fuelled intense local debate, along with a plethora of graffiti – WOT FOR?, WHY NOT? HOMES FOR ALL BLACK +WHITE. THIS HOUSE IS A NICE HOME, demonstrating, as Gaston Bachelard writes in Poetics of Space, that a house is not simply a building. All inhabited space, he argues, bears the essence of ‘home’. “Our house is our corner of the world…it is our first universe, a real cosmos in every sense of the word.” Wherever humans find shelter, they attempt to create the illusion of protection. A house, however modest, is not just a physical space but a fortress against the rest of the world, the site of our daydreams and theatre of memories. Part of an ongoing narrative that tells us who we are, the screen onto which we project the chronicle of our lives. The storehouse and site for our longings and aspirations, disappointments and losses: birth, copulation and death, past, present and future.

When we dream of the house where we were born, it becomes a metaphor for our past. Vanished voices and lost lives are imprinted into the very fabric of the walls. For Bachelard, a phenomenologist with a strong sense of the psychoanalytic, the topography of the house with its cellars, attics, nooks and corridors acts as a bodily analogy. It’s the site of our most intimate lives, our hidden psychological dramas in which our memories are collected. Events and traumas are shut in dark basements, hidden in attics. Memories exist in spaces. We remember where things happened. The dark cupboard in which we hid in as a child. The house we built under a table. We only have to return to them in our mind’s eye to relive our deepest emotions. The smells and textures of childhood come back to us with Proustian accuracy. Was that room really so large? Ah yes, and there was that mustard coloured wallpaper, those diaphanous curtains. And what was that familiar smell?

Born in Ilford, Essex, in April 1963, Whiteread’s mother Patricia Whiteread was an artist who took part in the landmark feminist exhibitions Women’s Images of Men and About Time at the ICA in 1980. Her father, a geography lecturer, took her, as a child, on field trips. Hers was a home, a house in which she was surrounded by art, ideas and left-wing politics. It made her what she was to become. Later, she’d go on to study painting at Brighton Polytechnic and complete an MA in sculpture at the Slade. But it was at Brighton, under the guidance of Richard Wilson, that she began to learn casting. Disinterested in traditional techniques or in replicating objects, she was attracted to negative spaces, to the underneath of a table or the inside of a sink or a hot water bottle (these she cast for many years in pee-coloured resin and pink dental plaster). Two early works, Shallow Breath 1988 and Closet 1988, both recall the dark and dusty hiding places – the underside of a bed, the inside of a wardrobe – those bitter-sweet childhood games of hide-and-seek. Influenced by the austere minimalism of Donald Judd and Carl Andre, there is, however, always a sense of the flawed, the vulnerable and the imperfect. The ghostly presence of the original object lingers, for this is a poetry of the mundane: the ordinary, the every day, the barely seen.

It’s this potential for nostalgic recollection that made Whiteread’s House such a rich and original work and set the standard for her future public art commissions such as the austere and poignantly silent concrete Holocaust memorial in Judenplatz Vienna, built-in remembrance to the Jewish Austrian dead.

House stood for just 80 days and was a lightning rod for public debate around social issues such as redevelopment and housing, as well as public art. Unveiled on 25th October 1993, it led to Whiteread becoming the first woman and the youngest artist to be awarded the Turner Prize. Uncannily this was on the same day that Bow Neighbourhood Council refused an extension to the lease on 193 Grove Road. Despite a number of stays of execution (including a parliamentary petition), House was demolished on 11th January 1994 in what must amount to one of the great acts of bureaucratic vandalism by any local council. Yet, despite their collective philistinism, House had already infiltrated the cultural imagination, setting a new standard for public art to come.

Top Photo: Courtesy Artangel Photo Detail: Denna Jones This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic

Sue Hubbard is an award-winning poet, novelist and freelance art critic. Her latest novel Rainsongs is published by Duckworth and her fourth poetry collection is due from Salmon Press this autumn.

Read More About Rachel Whiteread