What is painting for? Since the advent of the camera in the 19th century, its role has no longer been to transcribe reality – the photographic lens can do that with greater accuracy – but to interpret, through paint, what verbal language cannot: what it feels like to experience the world through our visual senses. No contemporary painter does this better than Sean Scully.

His blocks of muted colour evoke people, places, emotions and memories – SH

Many have dismissed his work as a series of coloured bricks or stripes, seeing him as an exclusively abstract painter, but that is to misunderstand his simplified rectangular forms. I have interviewed him numerous times. Behind his gruff exterior is a storyteller. A mythmaker. Literature is important to him and informs his work. Many of the paintings take their titles from works that have influenced him, from Becket’s Molloy to Blake’s Tyger, Tyger. Though apparently abstract and influenced in the 1970s by American minimalism and the likes of Robert Mangold and Robert Ryman, his paintings moved away from this formal elegance and constrained minimalism to convey the emotional experience of being alive. Rothko, Scully argues, is a more important painter than Ad Reinhardt.

His blocks of muted colour evoke people, places, emotions and memories. Deceptively simple they are, in fact, highly sophisticated and considered. Not just aesthetically but psychodynamically potent, they thrum with restrained emotion. The relationships between them are uncanny and unsettling. The slim apertures between rectangles suggest that they’re simply the first layer in a complex palimpsest of vision and emotional revelation. Their deliberate lack of perfection and inbuilt flaws imply human vulnerability and depth, currents that go on beneath the quiet visible surface and sensual brush marks. Scully has said: “I reacted against the idea of perfection and the holistic masterpiece. I wanted to make realities that were more humanistic, where the problematic relationships between things could make a new kind of spirit and beauty.”

He has, in the past, talked to me about his paintings in anthropomorphic terms, in contradiction to Clement Greenberg’s strictures that all narrative must be expunged from abstract art. Like Morandi’s bottles, the negative spaces between his coloured blocks speak of the relationships between people and the difficulty of intimacy, communion and connection. He may present as a Modernist, but underneath lurks a Romantic, one who has deep knowledge of the canon of western art on which he draws to expand his grammar of contemporary art.

Perhaps no other painting exemplifies this compressed emotion more articulately than ‘Paul’ (1984), an elegy to his 18-year-old, estranged son who was killed in a car crash. The broad sand and black horizontal stripes on the left of the canvas are violently halted by two columns of three vertical stripes that form a solid wall. There’s a small black space between the horizontal and the vertical areas where the cream-white paint forms a jagged rather than a neat edge. It reads like a transitional space, the hiatus between life and death, between then and now, that moment and this. It is so subtle that it’s easy to miss but the distinction between the two states is palpable. The horizontal stripes in the left-hand panel are full of energy. They thrust forward with the verve of a young life moving into the future, only to be blocked and brutally curtailed by the unforgiving verticals.

All Scully’s paint surfaces suggest skin and, therefore, by implication, the body. The creamy paint, here, might be read as light, the light of a future that should have rolled out – full of possibility – ahead of an 18-year-old boy, only to be cancelled by a heavy bar of black. The rust-red, suggestive of a pulsating life force, is, again, cancelled by a thick black line. It’s hard, too, not to draw an analogy between that and the colour of dried blood or a wound.

The three distinct parts of the work suggest an altarpiece triptych, but one where grief has cancelled any narrative element. Close observation will reveal that the central vertical column has slipped, that the edges are not true at the top and the bottom, poignantly suggesting a young life prematurely slipping away. Normally Scully’s stripes open up a picture but here they violently shut it down. Despite its apparent formalism, the painting wrestles between light and darkness, past and future, night and day, life and its extinction.

But Scully is never didactic. He is too much of a Modernist for that. As with Agnes Martin, mood is suggested through the placement and subtle application of paint rather than spelt out. We, the viewer, are asked to be open and sensitive to his suggestions, reading his nuanced colours and blocks of paint like braille to reveal more than their simple shapes. There is, too, something filmic about the painting that can almost be read from left to right like a series of cinematic shots that move through time to reveal their narrative.

Scully makes works that deal with passion and grief, dreams and fears. What it is to be flawed, vulnerable and human. He wants his paintings to have impact, to speak viscerally to the viewer who will imbue them with their own stories, their own emotions and relationships. Like potent music, they catch a mood, speaking to what is universal. Even so, he believes that art cannot be popularised without robbing it of its central ‘difficulty’ and thus its ‘mystery and morality, which is crucial to its survival. Having long ago left behind the beliefs of his Catholic childhood (he is of Irish extraction), he retains some of its values, even though he states “that in a time of intellectual and spiritual anarchy the most we can aim for are degrees of similarity [of thought and belief]. Our sense of certainty is gone.” In the 1990s, he was trying to make his paintings as extreme as possible, saying that “my work is an attempt to release the spirit through formal strength and direct painting,” but slowly, they became less rigid. A hungry, restless yearning threads through his later work, which hold all the stories he would like to tell, all the emotions he’d like to share. These are compressed, in their painterly mark-making, into the rectangles of his paintings. and none more so than in Paul.

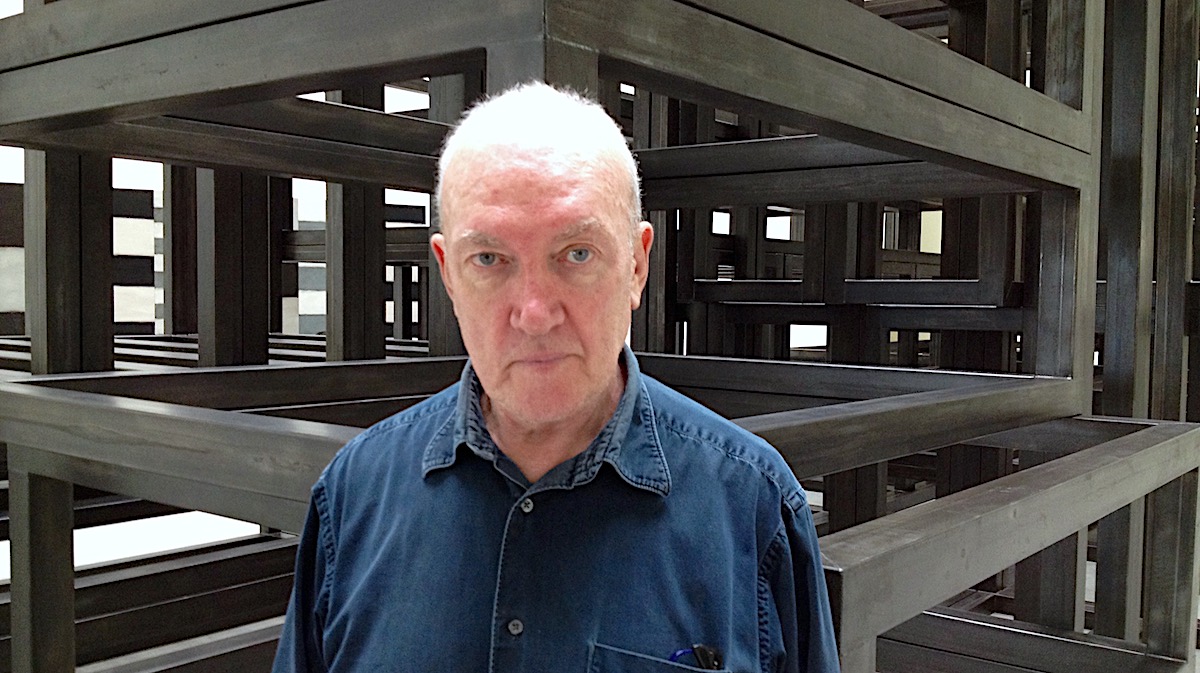

Top Photo: P C Robinson © Artlyst 2021

Sue Hubbard is an award-winning poet, novelist and freelance critic. Her novel Rainsongs is published by Duckworth, Overlook Press, US, Mercure de France and Yilin Press, China. Her fourth poetry collection, Swimming to Albania, is due from Salmon Press in the autumn.