The BLM protests in recent weeks have shown us how relevant issues of race still are. It’s shocking to see that racial discrimination still exists in this day and age. It is our role as cultural influencers to give our attention and support to the fight against systemic racism.

I am more than aware that I’m a white woman writing about this subject and I make no excuses as to my privileged status; however, keeping silent would be a far worse crime. We are living in times where we all need to speak up against racism and make our voices heard—the larger the crowd, the louder the noise.

Jack Whitten; Birmingham; 1964

The first work I would like to talk about is by American artist Jack Whitten. Whitten grew up in Alabama, with a childhood embedded in segregation and discrimination.

This particular work reflects his love for the abstract expressive political style of art. It is of such relevance today, as the starting point is a piece of newspaper, where one can decipher an image of an African American protester being attacked by a police dog. This event took place during a civil rights campaign in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. The artist covered up the image with darkly painted black canvas, to then tear it apart in a raw and scaring way. The painting represented resembles a layer of skin, letting appear a deep scar, symbolised by the image left behind.

The Door (Admissions Office); David Hammons; Wood, acrylic sheet, and pigment construction; 200.7 × 121.9 × 38.1 cm; 1969

This work by David Hammons is violently self-explanatory. Like a lot of Hammons’ work it has a performative aspect to it, he physically engages the viewer, by imprinting a body print onto an admissions’ office door. This work quite directly symbolises exclusion and alienation through the denial of entry. Hammons invites the viewer into a physical conversation about segregation.

Chris Ofili; No Woman, No Cry; Oil paint, acrylic paint, graphite, polyester resin, printed paper, glitter, map pins and elephant dung on canvas, 1998

The above painting depicts Doreen Lawrence, the mother of Stephen Lawrence, who was murdered in London in 1993 in an unprovoked racist attack. In this work, the mother is seen crying images of her son, which the artist collaged in the tears of his mum. This painting has an impact. It is packed with symbolism, especially as it sits on two big piles of elephant dung that could be interpreted as an allegory for the establishment that we rely on. Chris Ofili won the Turner Prize with this work.

Kara Walker: ‘Fons Americanus’ 2019 Hyundai Commission Tate Modern

The brutal history of the British Empire is conspicuous in its absence, forgotten and replaced with images of Glory and ‘Rule Britannia’. The art of Kara Walker plays in an important role in remembering the violent atrocities of the Empire. She records what has literally been burnt or buried. There is an irony, humour, and caricature in Walkers work, reflexivity and self-awareness that contrasts with a harsh and biting reality. Her recreation of The Queen Victoria Memorial outside Buckingham Palace in the Tate Turbine Hall is consistent with her previous work. The Georgian Silhouettes she chooses to recreate are the period equivalent of wearing Chanel, and the statue of Victoria is no different. She wants to remind us of American slavery and that problem is our problem. It is our legacy and the source of most of our wealth as a nation. It illustrates how we built our Stately Homes and Ornamental Gardens and how we funded the referenced statue of Victoria. By building a monument to the grim reality of the slave trade, she détournes our monarchy with a punk spirit in-keeping with the sex pistols.

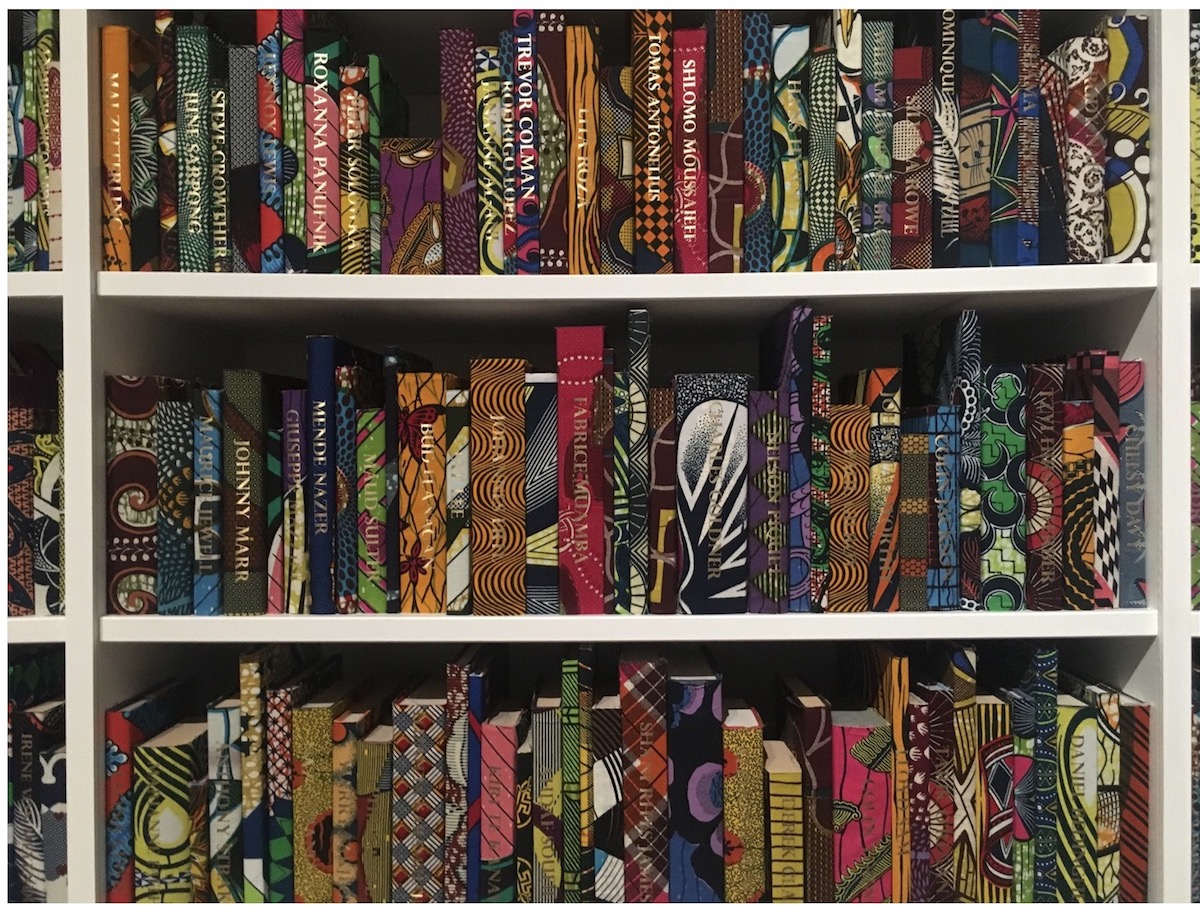

Yinka Shonibare; The British Library; 2014 (See top Photo)

Yinka Shonibare is one of the treasures of British art. He was born in Nigeria, but studied and now lives in London. This work is particularly interesting as it includes several languages used in his practice, all referencing symbolism associated with colonialism, cultural appropriation, and national identity. He is known for using the above-patterned wax material, which initially came from an overproduced Dutch copy of Indonesian dyeing. Indonesia was a Dutch colony in the nineteenth century. The patterns became widely used in traditional West and Central African garments.

I came across this installation at the Tate Modern. It is such an impressive, powerful room to be in. It consists of 2700 books, with spines embossed with the names of first or second-generation immigrants to Britain. It reminds us of the importance of inclusion and of the significant social improvements migration has made to British culture and history.

Basquiat; Untitled; 1981

Jean Michel Basquiat is one of the leading artistic voices of his generation when it comes to subjects of race and cultural alienation – being an African American at a time riddled with discrimination and racial profiling. The majority of his prolific body of work offers a reflection on slavery, discrimination, and racism. The above painting is an expressionist observation, and one could say a self-portrait, bathed in loneliness and martyrdom, a painted impression of how he felt in the face of society. He once said, “They’re just racist, most of those people,” in Dieter Buchhart’s Now’s the Time (Prestel). “So they have this image of me: a wild man running – you know, a wild monkey man, whatever the fuck they think.”