One of the things about this series is that it provides an opportunity to look back on keynote contemporary works with a degree of hindsight. This means that they have had time to ‘settle.’ That we can look at them, not through the lens of innovation and inscrutability, but rather observe the nuances and listen for reverberations that we might have missed first time around.

In 2013, the British artist Steve McQueen won an Academy Award for his feature film 12 Years A Slave, an emotionally powerful movie about a life of black enslavement in 1850s America. (He had already won the Turner Prize in 1999 for his ‘clarity of vision and range of work’). 12 Years A Slave made McQueen a household name. He didn’t go to film school, training instead as an artist at Goldsmiths, followed by a short (but not very enthusiastic) spell at Tisch School of Arts in the States. As a result, he spent the best part of 15 years making short movies. Among his most famous is Deadpan (1997).

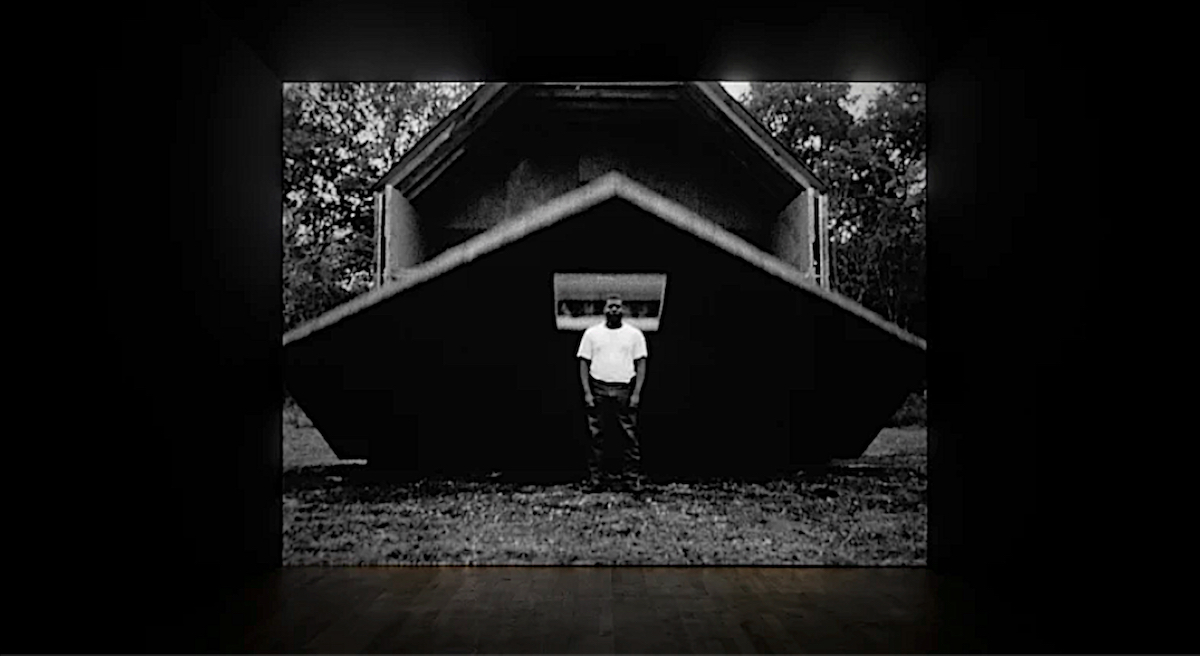

Deadpan is based on one of the most iconic moments in silent film. The legendary scene in Buster Keaton’s 1928 film Steamboat Bill Jr, in which Bill (played by Keaton) is battered and blown by a hurricane, just before a house collapses around him. Luckily for Bill, he is positioned exactly in the spot where there’s an open window, so when the house does hit the ground, he escapes unscathed. Although a ‘silent’ movie, it’s not actually silent, being accompanied as most films of this period were by exciting music that sets the emotional tone. McQueen’s 4-minute and 35 seconds black and white film, where he re-enacts this Keaton moment, is absolutely silent. Without music directing our emotions, what was originally laughter generated by slapstick behaviour, very soon takes on a more ominous and tragic note.

The term Deadpan implies dry humour. Stony-faced neutrality contrasts with the ridiculous and absurd nature of what is taking place. Yet McQueen’s use of multiple angles and perspectives leads to a sense of discombobulation, to an emotional destabilisation that undercuts this traditional reading. Instead of humour, we sense trauma.

An early shot shows McQueen standing in the dirt in shoes that have no laces. Is this because they’ve been removed by some authority or detention centre to prevent suicide? And if so, what was he doing there and how has he escaped? What was cause for merriment in the Keaton film now seems fraught with potential anguish. Here there is no hurricane, no hectic music. Just a tall, imposing black man standing in what looks like an empty field as a house falls flat around him. The window space that saves him is a dark square, as black as any Malevich painting, so he seems to be swallowed up by a deep void, to disappear into infinity. Standing tall on the stony ground, his face is unflinching, stoic even, as though this collapse is just another piece in a jigsaw of suffering to which he has been all too frequent a witness. I couldn’t help but think of all those impoverished black workers whose meagre shacks were destroyed by racist vigilantes or those driven Grapes-of-Wrath-style from unproductive, dust-bowl land without the benefit of welfare and no means of support. Or, perhaps, in fact, it is the visual fantasy of a man who has been incarcerated for too long, dreaming about smashing down the walls that surround him and making a break for freedom.

McQueen’s own background didn’t give him the most promising of starts. The son of Trinidadian and Grenadian immigrants, he grew up on the notorious White City Estate in Shepherd’s Bush and was ‘rescued’ by his mother, who moved the family to leafy, suburban Hanwell. At school, he was dyslexic, wore a patch for a lazy eye and was told he’d never amount to anything and be fit only for manual work. His experience of toxic racism and lack of educational expectation could have pushed him into anti-social behaviour and petty crime, but it drove him towards achievement. “I think, “ he has said, “when you’ve been fucked over as a child… you release what’s up, you think, OK, this is a stupid game and I’m not playing that. I’m going to tear it the fuck down.’ He has said that he was saved by art. ‘I loved art. I loved art, I loved art.’ What fascinated him was that it wasn’t about ‘a complete idea, [but] about having a tenth of an idea and then amalgamating it with something.’

Deadpan is notable for doing just that. It is not about anything. It is simply a short film that shows the wall of a house falling around a silent black man. But, as with a good poem, the work suggests multifaceted meanings. What McQueen has created is a space between expression and experience, between language and being, that allows room for creativity and critique, resistance and change. For all the slapstick humour of Keaton’s original film, Deadpan is deadly serious: an artwork that deconstructs our expectations and challenges the way we think.

Sue Hubbard is an award-winning poet, novelist and freelance art critic. Her latest, highly acclaimed novel, Rainsongs, is published by Duckworth and her fourth poetry collection, Swimming to Albania, is available at www.salmonpoetry.com. Later this year, Pushkin Press will be re-issuing her second novel on the life of the expressionist Paula Modersohn Becker to coincide with the RA show The Making of Modernism. They will publish her fourth novel, Flatlands, in 2013.

Top Photo: Still Steve McQueen Deadpan courtesy Thomas Dane Gallery and the Artist