November’s art diary begins with exhibitions by artists (including Lakwena Maciver, Hannah Rose Thomas, Tuli Mekondjo, and Paul B. Kincaid), about which I’ve written previously or with which I have worked, and venues with similar connections, mainly with a link to spirituality. Then, there are exhibitions of work by significant artists who have had or have spiritual inspirations, including Stanley Spencer, Sister Corita Kent, Sean Scully, and Edmund de Waal. I conclude with several environmentally themed exhibitions at The Arc, the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, and the Nevada Museum of Art, as well as an exhibition in Mexico City on the theme of failure.

‘LAKWENA – HOW WE BUILD A HOME’ is a vibrant new exhibition of cardboard and bead paintings by Lakwena Maciver at Wellington Arch. In this new body of work, crafted from found cardboard boxes and plastic beads, Maciver transforms remnants of trade into vibrant, graphic paintings —recasting the language of commerce into bold affirmations and reminders of hope, beauty, and home.

These materials, seemingly modest but rich in narrative, were sourced from Ridley Road Market, which is beneath Maciver’s studio and nearby her home in East London. This iconic London street market has been home to many different communities over time and is now known for its African and Caribbean hair shops and food stalls, making it a vital hub of Black British culture and everyday life.

Reflecting on these materials, Maciver notes: “I’m interested in the small everyday, domestic exchanges and negotiations and the many unknown people along historic trade routes that have enabled me to hold in my hand a banana grown thousands of miles away that gives me a taste of another home.” Her words invite us to consider the many hands and lives – past and present – that come together in the objects we hold and the lives we build, tracing connections that stretch across time and place.

Her practice has long blended art, design, fashion, and spirituality, reaching audiences far beyond traditional galleries. Her murals and public works, from the Bowery Wall in New York to installations at Tate and Somerset House, have made her one of the most recognisable artists of her generation. Her work often engages with public spaces to interrupt or reframe those environments, bringing gently subversive messages and bold colour into areas often defined by institutional or historical weight.

By presenting this most recent body of work at Wellington Arch, a historic monument once intended as a gateway to London, she invites reflection on how this symbol of Britain’s past might also connect with the many different identities and stories that shape the country today. The Arch, designed to represent military victory and Britain’s global influence, stands as a reminder of authority and national pride. Yet, atop the structure is a statue of the angel of peace descending on a chariot of war, an image that gently suggests the complexities of power and the hope for coming together.

This setting opens a space to reflect not only on Britain’s imperial legacy, but also on its entangled histories of migration, trade, and cultural exchange, offering a more expansive view of influence that includes the everyday and the unseen. In doing so, she questions whether Britain’s global impact might also be celebrated through narratives that move away from conquest and toward resilience, shared memory, and the everyday work of building a home together.

Hannah Rose Thomas is exhibiting a new portrait,’Nasreen’, at Grace Farms as part of an ongoing exhibition ‘With Every Fiber: Pigment, Stone, Glass’ that demonstrates innovative approaches to ethical sourcing and proves that fair labour practices in the construction industry are within our reach.

‘Nasreen’ is a portrait of Nasreen Sheikh, a modern slavery survivor, human rights activist, artist, and Founder of The Empowerment Collective. The portrait was created using egg tempera paint mixed from natural pigments — a technique traditionally used for religious art. Thomas’s use of iconography and early Renaissance painting techniques, combined with gold leaf, is symbolic of the restoration of dignity and the sacred value of each individual.

In this exhibition, the stories of pigment, stone and glass are told through a number of newly commissioned artworks. In addition to Thomas’ portrait of Nasreen Sheikh, the exhibition includes: a painting by artist and professor, John Sabraw, using pigments made in his studio from recycled mine drain off in the Ohio mountains; a new glass installation by Nina Cooke John, Principal of Studio Cooke John Architecture and Design and designer of ‘With Every Fiber’; and a sustainable prototype for stone truss work demonstrating engineering solutions, designed by Steve Webb, of Webb/Yates, and fabricated by the Stone Masonry Company. The London Philharmonic Orchestra, which has a long partnership with Grace Farms, has also recorded ‘Woven in Tears’ — a new composition by Evan Williams created for this exhibit and heard within the installation.

Tuli Mekondjo is exhibiting at St James’s Piccadilly as part of ‘Art in the Side Chapel’, a programme curated by the Revd Dr Ayla Lepine, Associate Rector at St James’s and an art and architecture historian in parallel to her role as a member of the clergy. These temporary exhibitions invite visitors to reflect on the transformative power of creativity and faith through the lens of intersectionality. With an exhibition title in Oshiwambo, English and Finnish, Namibian artist Mekondjo focuses on social justice and spirituality as she examines the rise of missionary-led Christianity in northern Namibia during the late 19th century. In this process, Mekondjo asks broader, pressing questions about the relationships between colonialism, African spirituality and the need for healing and re-rooting among many African peoples, both on the continent and across the Diaspora.

Welsh sculptor, Paul. B. Kincaid’s work can be found at the Courtyard Gallery in Hereford. His background as a Catholic and his continuing faith are manifested in all his sculptures, from a monumental depiction of St. David in the Vallée des Saints in Brittany, to Adam and Eve; Christ on the Cross; and much more. He also has work on public display in the National Botanical Garden in Wales; Newport in South Wales; Rohan in Brittany and the Carmarthen School of Art. When describing his sculptures, he likens them to angels, as “difficult earth-born images”. Not the soft feathered Seraphim of familiar thought instead” a heavy, muscular manifestation that pushes out of a dark concentrate, a kind of rich physical loam that contains the seed of life” – “Dust thou art and unto dust thou shalt return.” These are fixed objects that will not rest; images of sex and death; a paradox of stone that would be flesh.

Miriam Warner writes that: “The production of Kincaid’s pieces is ritualistic process, ideas are drawn from the subconscious mind and given form by stages: collages of restricted visual matter, chosen by primary response, focus the attention and precede drawings, clay models and finally, carved stone. These models are not slavish transcriptions of anatomical studies, but figurative images, whose structural anatomy is determined by the folded sheet clay; it is this anatomy that carries the spirit of each piece. The fluidity of form produced by this technique, provides the basis of its final transition into stone; Kincaid views consideration of this anatomy in his work as ‘a communication with the non perceived. The Body Mythical and Spiritual’.”

Ceramic artist David Millidge returns to RHS Garden Hyde Hall with a new exhibition alongside string sculptures by guest artist Sam Jacobs. Millidge’s work includes abstract forms, functional pots and figurative sculpture. The thing that ties all these genres together is his unique construction technique. His method of assembling slip-cast forms allows him complete creative freedom. His works, which usually contain some ambiguity, are unusual, stimulating and thought-provoking. This exhibition features 100 pieces, including his most recent works inspired by Egyptian artefacts. Jacobs is a British sculptor based in Brighton. She creates complex, three-dimensional sculptures appropriating traditional knotting techniques. She has a strong interest in historical knotting, sustainable materials, and the potential of public sculpture to create connections and conversations.

Mark Lewis has a second solo exhibition at The View Gallery, which features many of his recent drawings of Epping Forest and its environs, including ‘Strawberry Hill Ponds, Epping Forest’ and ‘Under the M11, South Woodford’.” Lewis is an artist, designer, silversmith, educator, and public speaker, currently focusing on landscape painting and drawing, as he has a longstanding interest in contemporary approaches to both. He was a principal lecturer in the John Cass Department of Art, Media and Design at London Metropolitan University until 2009 and has also taught at the Birmingham School of Jewellery and the Goldsmiths’ Centre in London. Drawing has always been central to his practice, and recent work has focused significantly on gesture and mark-making to create forms of visual shorthand. He extensively promotes these techniques in a variety of educational contexts as methods of capturing the essence of form and structure and a way of liberating creative thinking.

Fitzrovia Chapel is presenting ‘Children of Albion’, a powerful new exhibition by London-based British artist Ben Edge. In this showcase of painting, sculpture, and film, Edge continues his deep dive into British folklore and mythology – mining the ancient stories and rituals rooted in the land to uncover their enduring resonance in a modern world marked by disconnection. In this exhibition, Edge captures what he calls a “Folk Renaissance,” reflecting a rising desire to reclaim ancestral roots and reconnect with nature. But ‘Children of Albion’ is no exercise in nostalgia. Instead, it’s a forward-looking vision, an invitation to re-enchant our relationship with the land and reimagine a shared cultural identity that bridges past, present, and future.

Edge’s works conjure ancient sites and the mythologies that surround them, where demons, superstitions, and timeless tales take shape within today’s fragmented world. From Summer Solstice celebrations in Milton Keynes to ritual scenes inspired by the folk song John Barleycorn, Edge’s works teem with hybrid figures – part man, part animal, part plant – and spectral presences that exist beyond time. In an increasingly urban world, these works serve to remind us that we are not separate from nature, but part of it – deeply and inextricably woven into its fabric.

Through these works, Edge blends tradition with the tensions of modern life – grappling with environmental collapse, identity crises, and a collective yearning for meaning. “As contemporary Britons, I believe we’re all part of this evolving story,” Edge says. “It transcends time and heritage, forming a diverse, interconnected whole. Since the pandemic, I’ve seen a renewed fascination, especially among younger generations, with folk traditions and the spiritual power of the land.”

At the heart of the exhibition is the painting ‘Children of Albion’, which serves as a dramatic altarpiece in the Chapel. It offers a sweeping visual history of Britain, from prehistory to the present. Inspired by the fantastical complexity of Hieronymus Bosch, it explores the unravelling of our bond with nature while confronting Britain’s colonial legacy. Through themes of migration and transformation, Edge reclaims Britain as a “mongrel nation” – a place shaped by waves of cultural exchange and constant evolution.

Stanley Spencer (1891-1959). Study for the Resurrection, c. 1920-21, Private Collection © Estate of Stanley Spencer.

The most ambitious exhibition dedicated to Stanley Spencer in a decade is currently on display at Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury, before transferring to the Stanley Spencer Gallery, Cookham, from April 2026. Spencer’s art was rooted in both his relationships and a deep sense of place. Although Spencer’s life and career are largely synonymous with his native village of Cookham in Berkshire, he also spent a great deal of time in Suffolk, most notably Wangford and Southwold on the coast. His association with the county spanned four decades, initially through the experience of his first wife, Hilda Carline.

Drawing on new research, this exhibition will explore Spencer’s personal relationships and artistic development through his visits to Suffolk in the 1920s and 1930s. Spencer married fellow artist Hilda Carline in Wangford, Suffolk. The couple were joined on their honeymoon by Stanley’s brother Gilbert, who had introduced them. The previous year, Hilda, her brother, the artist Richard Carline, and Stanley had all stayed in Wangford, where their artistic practice and personal relationships developed in tandem.

Spencer developed a sense of Cookham as a village in heaven during his childhood. He never lost that child-like vision, although at times he questioned whether it had been successfully retained. Despite many poor choices and challenging life experiences, he carried a child-like sense of wonder through his life and work, and as a result, left as his legacy the deepest and broadest vision of heaven in the ordinary that any artist has been able to gift to us.

“In a sense, the whole world around the artist is his source, his sorting and relating powers are his sorcery, and the one isn’t much good without the other. … Anything can be a source, even a mistake. The sorcery or the thievery is the art of relating sources into a new solution.” These were the insights of Corita Kent, an artist, teacher and activist who uniquely combined her passions for faith and politics in an exuberant and joyfully creative practice. As a Catholic nun in Los Angeles’s Immaculate Heart of Mary order and an influential art teacher at Immaculate Heart College from 1947 to 1968, Corita (as she was known) gained international recognition for her signature serigraphs (silkscreen prints) that innovatively brought together elements of popular culture with messages of love, faith and social justice. Over the course of several decades, Sister Corita developed a unique and inventive approach to typography and colour that rivalled the explorations of her Pop Art contemporaries.

‘Corita Kent: The Sorcery of Images’ focuses on a lesser-seen aspect of Sister Corita’s artistic practice: her archive of over 15,000 35mm slides, which she and her colleagues took between 1955 and 1968 while she was a beloved teacher in the art department at Immaculate Heart College. Collecting fragments of the world with her camera for reuse at a later date, her eye documented the contemporary Los Angeles urban landscape of advertising and billboards, social events such as the effervescent and carnivalesque processions of the college’s Mary’s Day celebrations, dolls and puppets, flowers, and many other often-overlooked moments of everyday wonder.

This exhibition brings together over 1,100 images from Corita’s photographic archive in an effort to show how photography was an integral part of her artistic practice as both a source and an inspiration. Presented as a three-screen digital slide projection that pays homage to Corita’s multi-screen slide show lectures, ‘Corita Kent: The Sorcery of Images’ offers a unique look at this photographic archive, combining and recombining images in an exploration of her joyful and idiosyncratic way of seeing the world.

Sean Scully, Untitled, 1967; Blue Wall, 2024.

Copyright the artist, courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac.

The Estorick Collection is currently presenting a special intervention by Sean Scully, which showcases a body of his work alongside that of Italian master Giorgio Morandi. This pairing reflects Scully’s longstanding dialogue with the imagery of Morandi, who, though ostensibly a figurative painter, “learned the lessons of abstraction”, as Scully observes. ‘Sean Scully: Mirroring’ features 20 works by Scully, which date from 1964 to the present day, shown alongside a dozen Morandi etchings and drawings from the Estorick’s permanent collection. Encompassing works on paper, paintings and sculpture, many of these new or rarely seen works trace the arc of Scully’s practice, from early representation to geometric abstraction and eventually back to figuration, a journey that mirrors Morandi’s own evolving trajectory.

The works in ‘if you came this way’ at the Gagosian’s Beverley Hills location consist of Edmund de Waal’s porcelain vessels, lyrically arranged in vitrines alongside glimpses of other materials, including gold, silver, lead, marble, aluminium, alabaster, and Kilkenny stone. These installations act as repositories of memory, archives, and language. They are intended to invite slow looking and contemplation. (see lead image)

In the series ‘if you came this way’, de Waal has, for the first time, displayed his vessels in gilded vitrines, where gold leaf has been applied to oak using a technique that is thousands of years old. Many combine the radiant aura of gold with brushed-on liquid porcelain, creating a new materiality that evinces porcelain’s historical designation as “white gold.” These works respond to devotional images by Duccio, Giotto, and other Proto-Renaissance artists. The housing of vessels within golden structures recalls reliquaries: containers of sacred objects. Other large-scale installations ‘as if even now you were sleeping’, ‘rain diary’, and ‘as long as it talks I am going to listen’ hold many groupings of vessels to form topographies resembling lines in a poem or music in a score.

For de Waal, his installations are a kind of poetry. Many different voices are held in the works of this show, where de Waal has inscribed fragments of poetry into porcelain tiles that sit alongside his vessels. The titles of the works are drawn from texts by Matsuo Bashō, Paul Celan, T. S. Eliot, Louise Glück, Li-Young Lee, Thomas Merton, Marianne Moore, Charles Olson, and Marco Polo—studies of homecoming, exile, and the fugitive lands of memory. The exhibition’s title draws from a line in Eliot’s poem “Little Gidding” (1942), a meditation on place, pilgrimage, destruction, and renewal. The poem’s central image of fire speaks to the alchemical transformation of clay into ceramic in the heat of the kiln. “My whole life is trying to think about place and displacement — how things, people, and stories move, often against their will, across borders,” de Waal observes. “I work with these themes in the objects that I make, finding spaces where they can be held in a place of some safety.”

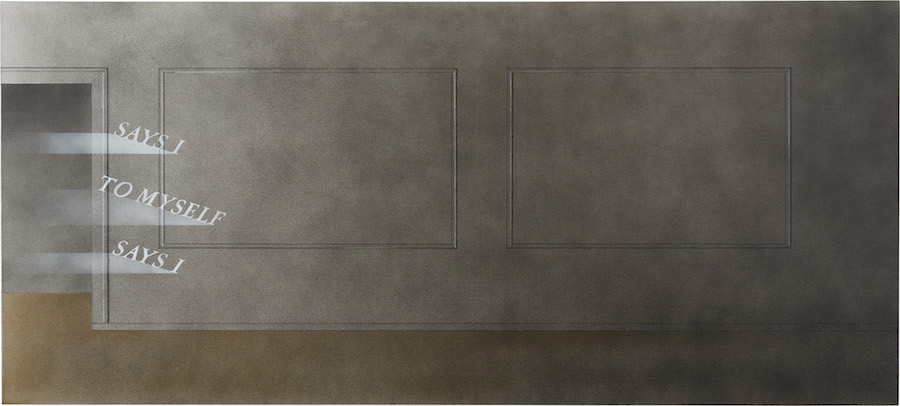

Ed Ruscha, Says I To Myself Says I, 2025, acrylic and graphite on canvas, 54 × 120 inches (137.2 × 304.8 cm) © Ed Ruscha. Photo: Jeff McLane

Since the 1960s, Ed Ruscha has consistently foregrounded the strangeness of everyday language, exploring how the relationships between words and images transform the meanings of each. He has spoken previously about the influence that the Catholicism of his youth had on his work, with dual associations, blends, and juxtapositions being at the heart of that influence. In new paintings on view at Gagosian’s Paris gallery, he shifts from the representation of public-facing façades to the quiet drama of private interiors. Also, 10 new works on raw linen at Gagosian’s Davies Street gallery in London establish visual and textural contrasts between the painted words and images and their supports, emphasising their definition and potential.

Over the course of six decades, Ruscha has frequently returned to architecture and infrastructure as subjects, depicting gas stations, apartment buildings, parking lots, museums, houses, and industrial sites as seen from the street and from the air. The paintings of ‘Talking Doorways’ in Paris move for the first time from exteriors to interiors, using subtle gradients of stippling to depict rooms that are bare except for decorative moulding and doorframes. In addition, each work features a doorway through which a painted phrase appears, crossing the threshold and accompanied by trailing linear bands that suggest both beams of light and the soundwaves of spoken words.

Ruscha’s investigation of interiors was triggered in part by the work of Danish artist Vilhelm Hammershøi. Best known for his enigmatic paintings of light-filled rooms that are either empty or occupied by a single figure, Hammershøi crafted works that are restrained in palette and closely observed, evoking a sense of quiet attentiveness. Reflecting on his consideration of Hammershøi’s paintings, Ruscha notes: “I began to see the insides of walls with mouldings and wainscoting and little curbs and things that intrigued me. And while my work is nothing like his, I can say that his work has inspired me. He’s more plainspoken and downright rigid compared to what people do today. Formal and rigid and cold, but still making a true statement.”

Ruscha’s new works also convey a sense of interiority, though their feeling of quietness is disrupted by the painted texts, suggesting a conversation or monologue. Stretching 10 feet, ‘Says I to Myself Says I’ features the titular phrase, which voices an introspective enunciation mined from vernacular language, divided into three bands that emphasise the palindromic repetition of “Says I.” A visualisation of talking through the frame of a doorway, it is also a declaration of Ruscha’s ongoing inquiries into art and language.

The Garden at Kelmscott Manor by Marie Stillman, 1905, watercolour © Society of Antiquaries of London (Kelmscott Manor)

Hampshire Cultural Trust is presenting the first-ever exhibition to show how natural beauty inspired the radical imagination and art of the Morris family. ‘Beauty of the Earth’ features designs by William Morris along with work by his daughter May and wife Jane, plus artworks by other Pre-Raphaelite artists including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Ruskin, Edward Burne-Jones and Marie Spartali Stillman. It reveals how the Morrises’ love for gardens and green spaces was woven into all aspects of their lives, from patterns to politics. Their art remains beautiful, fruitful and radical.

The exhibition at The Gallery at The Arc, Winchester, comprises more than 50 objects, with significant loans travelling to Hampshire from institutions such as the William Morris Society, the Victoria and Albert Museum, Kelmscott Manor, and the Ashmolean Museum, along with objects drawn from the collections of the British Library and private lenders. There are ceramics, textiles, wallpapers, prints, personal items, books, and poetry – all demonstrating the variety of media in which the Morris family worked. Guest Curator, Suzanne Fagence Cooper says: “We are able to display fragile textiles, original photographs and delicate works on paper, to tell unexpected stories about the women and men who shaped the Arts and Crafts movement.”

The displays demonstrate how sensitivity to natural beauty was central to William Morris’ work. His designs for the home, his lyrical poetry, and even his political activism were all underpinned by his care for the landscapes he cherished. Indeed, Morris once said that he hoped everyone could enjoy “possessions which should be common to all of us, of the green grass, and the leaves, and the waters, of the very light and air of heaven”, and urged us all to “love the narrow spot that surrounds our daily life.” The exhibition features a specially commissioned sound piece that captures the sounds of Kelmscott Manor, connecting to the ecology, experience, and landscapes of the charming 17th-century house that Morris described as “heaven on earth”.

For its Madrid premiere, John Akomfrah’s most ambitious exhibition to date, ‘Listening All Night to the Rain’, features a special introduction with selected works from the Thyssen-Bornemisza collections, showcasing artists such as Miró, Fontana, and Klein. The exhibition is a cycle of video installations – called Cantos – that weave together archival footage, newly shot film sequences, and immersive sound. The five monumental Cantos combine film, sound, and archival material, addressing colonial legacies, migration, racial injustice, and the climate crisis. Flowing through the installations, water becomes both a symbol of diaspora journeys and a metaphor for the survival of memory across time and continents.

The exhibition takes its title from an 11th-century poem by the Chinese writer Su Dongpo, written during his period of political exile, which reflects on the transitory nature of life. Layering archival images, voices, and sounds with newly filmed footage and staged tableaux, Akomfrah creates a kind of manifesto that positions listening as a form of activism. The installations summon histories of colonial resistance, environmental devastation, and migration, while offering space for reverie, memory, and monumentality. For Akomfrah, “the key metaphor, the key visual trope, is flooding. It speaks to climate change, but it’s also about rethinking what our past has been. Listening to your past is a good exercise.” Together, the Cantos invite audiences to slow down and listen to voices from the past and present, to stories of displacement and resilience, and to how sound and water can carry memory across generations.

Nevada Museum of Art is debuting ‘Into the Time Horizon’, a groundbreaking multi-year exhibition that transforms the museum’s entire 120,000 square foot building. This immersive show is the largest in the institution’s history, and the first to occupy every gallery and public space simultaneously, inviting visitors to imagine a future in which humanity interacts with our planet in an ethical, responsible, and caring manner. Spanning several new museum spaces, ‘Into the Time Horizon’ brings together nearly 200 diverse artists from around the globe to confront the climate crisis, one of the most pressing issues of our time. Through an extensive range of media, the exhibition asks how art might help reimagine humanity’s relationship with the Earth itself.

The exhibition takes its name from a concept most used in economics, the time horizon, “a fixed point of time in the future at which point certain processes will be evaluated or assumed to end.” In his novel’ Ministry for the Future’, participating writer Kim Stanley Robinson reimagines the time horizon as the narrowing window that remains to avert the most cataclysmic effects of climate change. It is within this interval, between possibility and catastrophe, that ‘Into the Time Horizon’ situates itself. Apsara DiQuinzio, senior curator of modern and contemporary art, says: “Into the Time Horizon brings together artists who are probing the limits of our current trajectory while also envisioning radically different futures. At this precarious moment, art offers a space to recognise the urgency of our situation and how we might alter the course ahead.”

Installed sequentially, the exhibition unfolds in seven sections, with themes titled ‘Listening to the Land’, ‘Interspecies Relationships’, ‘Circularity’, ‘Altered Lands and the Anthropocene’, ‘This Vital Earth’, ‘Strange Weather’, and ‘The Sixth Extinction’. ‘Into the Time Horizon’ challenges visitors to confront climate realities while also offering solutions of hope and collective action. The conceptual heart of the show is the section titled ‘Listening to the Land’, which foregrounds Indigenous knowledge systems that long preceded modern environmentalist movements. Featuring work by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, First Nations, and Native American artists from the Great Basin and beyond, this section underscores the central role Indigenous communities play in modelling sustainable and reciprocal relationships with the natural world. Roughly 35% of participating artists are Indigenous.

Finally, the Museo de la Ciudad de México is presenting ‘Columna Rota/Broken Column’, an exhibition that brings together more than 125 contributors to examine rejection as a structuring force in both private life and collective history. This project also reframes the idea of authorship as, rather than representing a single curatorial voice, the exhibition unfolds through a chorus of artists, writers, performers, and archival documents, positioning Mexico City at the centre of a global conversation on experimental and politically engaged art.

Extending across the Museo de la Ciudad de México, the neighbouring Church of Jesús Nazareno, and the surrounding streets, the exhibition situates rejection as both subject and method. Its location is itself symbolic: the intersection where legend places the first meeting of Hernán Cortés and Moctezuma II, and where an Aztec serpent monolith is embedded in the colonial palace façade. Inside the church, José Clemente Orozco’s rarely seen late mural ‘Apocalypse’ sets the tone of defiance and rupture.

The works gathered for ‘Columna Rota’ are as diverse as the experiences of exclusion they evoke. In the museum’s central courtyard, José Eduardo Barajas has created a twenty-by-twenty-metre painting suspended overhead, converting the open air into a canopy of colour and shadow. Teresa Margolles, in her searing installation ‘In the Air’, releases delicate soap bubbles formed from water that once washed the bodies of the dead, collapsing beauty and mortality into the same breath. The work is rooted in Mexico’s ongoing human rights crisis, where thousands have been killed or forcibly disappeared in recent years, making the piece both a memorial and a political reckoning.

On the façade, Alfredo Jaar’s ‘A Logo for America’, a landmark of Latin American conceptual art, appears on a monumental LED screen mounted above an Aztec monolith. Mexico’s leading experimental theatre collective, Lagartijas Tiradas al Sol, is animating the building each week with performances that extend the exhibition into the register of lived time. A new intervention by Ramón Saturnino transforms the museum’s galleries into a field of barriers that draw on the language of institutional censorship. Originally conceived for the courtyards, the work’s relocation underscores the exhibition’s engagement with the politics of visibility and restriction.

Alongside these interventions, the exhibition incorporates international voices such as Marlene Dumas, Lutz Bacher, and Dayanita Singh, whose works resonate with questions of vulnerability, intimacy, and refusal. Contributions from Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa and Juan Pablo Echeverri, two leading queer Latin American artists, deepen this conversation through their explorations of identity and intimacy. Tamiji Kitagawa, the Japanese modernist, returns to Mexico to reconnect with a geography that shaped his artistic trajectory. Meanwhile, Thomas Mukarobgwa, a pioneering figure from Zimbabwe, is being foregrounded internationally for the first time since his work was championed by Alfred Barr and Tristan Tzara. Together, these artists underscore the exhibition’s commitment to reactivating overlooked and marginalised histories within global modernism and to positioning Mexico City as a critical site for their rearticulation.

Curator Francisco Berzunza says: “We speak little about the role rejection plays in shaping who we are—how it defines who belongs in our world and the world at large, who doesn’t, how soul-shattering it can be; and yet, how powerfully it can propel our projects, our ideas, and ourselves.

For years, I’ve wanted to make an exhibition around the concept of rejection. As I struggled to put into words how it feels to be rejected—other than shit—I turned to Frida Kahlo’s 1944 drawing Boceto preparatorio para la columna rota [Preparatory Sketch for The Broken Column], which depicts the artist’s mutilated spine as a fragmented Ionic column. The metaphor of the crushed structure which holds humans and buildings alike, resonated with me as I thought about my own trajectory as an exhibition-maker, which has mostly gone unnoticed; my romantic life, which feels like a perpetual yearning; and my own condition as a chronic nitpicker.”

The Museo de la Ciudad de México, once a beacon for international exhibitions, has been left in disrepair in recent years, its programming eroded by bureaucracy and years of cultural neglect under previous administrations. ‘Columna Rota’ thus arrives not only as an exhibition but as an act of resurrection. Entirely funded by civil society, it insists on culture as an autonomous force, independent of state neglect and institutional complicity. “The museum is literally in ruins,” Berzunza observes, “and this project is about bringing it back to life.”

LAKWENA – HOW WE BUILD A HOME, 15 October – 14 December 2025, Vigo Gallery, Wellington Arch, London – Visit Here

‘OMUUA OKU LI POPEPI: THE LORD IS NEARER: HERRA ON LÄHELLÄ: Tuli Mekondjo’, 13 October – 12 November 2025, St James’s, Piccadilly –

Visit Here

‘With Every Fiber: Pigment, Stone, Glass’, ongoing, Grace Farms, Connecticut – Visit Here

‘Paul Kincaid’, 7 November 2025 – 10 January 2026, The Courtyard Gallery, Hereford –

Visit Here

A Solo Exhibition by David Millidge, 7 November – 16 November 2025, RHS Hyde Hall – Visit Here

‘A Silent Frenzy’, 4 – 30 November 2025, The View Gallery, Chingford – Visit Here

‘Ben Edge: Children of Albion’, 6 – 26 November 2025, The Fitzrovia Chapel – Visit Here

‘Corita Kent: The Sorcery of Images’, 26 September 2025 – 24 January 2026, Marciano Art Foundation, Los Angeles – Visit Here

‘Love & Landscape: Stanley Spencer in Suffolk’, 15 November 2025— 22 March 2026, Gainsborough’s House –

Visit Here

‘Sean Scully: Mirroring’, 8 October – 23 November 2025, Estorick Collection – Visit Here

‘if you came this way’, 13 November – 20 December 2025, Gagosian, Beverly Hills –

Visit Here

‘Ed Ruscha: Talking Doorways in Paris’, 22 October – 3 December 2025, Gagosian, Paris –

Visit Here

‘Says I, to Myself, Says I’, 14 October – 19 December 2025, Gagosian, London –

Visit Here

‘Beauty of the Earth: The Art of May, Jane and William Morris’, 15 November 2025 – 4 February 2026, The Gallery at The Arc, Winchester – Visit Here

‘Listening All Night to the Rain’, 4 November 2025 – 8 February 2026, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza –

Visit Here

Into the Time Horizon at Nevada Museum of Art will open in sections including: ‘Ernesto Neto: Children of the Earth’, 15 November 2025 – 20 September 2026; ‘Maya Lin’, 15 November 2025 – 31 May 2026; ‘Listening to the Land ‘, 31 January 2026 – 21 February 2027; ‘Strange Weather ‘, 21 February 2026 – 29 November 2026; ‘The Sixth Extinction ‘, 21 February 2026 – 29 November 2026; ‘Circularity ‘, 21 February 2026 – 29 November 2026; ‘Interspecies Relationships ‘, 21 February 2026 – 29 November 2026; ‘This Vital Earth ‘, 28 February 2026 – 3 January 2027; ‘Pierre Huyghe: Human Mask ‘, 28 February 2026 – 3 January 2027; ‘Altered Lands and the Anthropocene ‘, 28 March 2026 – 20 September 2026.

Visit Here

‘Columna Rota/Broken Column’, 8 November 2025 – 22 February 2026, Museo de la Ciudad de México –

Visit Here