September provides an opportunity to look back as well as look forward. The celebrations for the centenary of Francis Newton Souza’s birth culminated in the first half of 2025. Other work exploring Christian themes or by Christian artists can be seen at MOCA Machynlleth, Gilbert White’s House, 54 Gallery (Society of Catholic Artists), Bradford 2025 (Methodist Collection of Modern Art), and The Mayor Gallery. Exhibitions of work by Marian Spore Bush and Sean Scully draw on the inspiration of nature, while Spore Bush and Juliette Minchin take inspiration from spiritualism and mysticism. Lucy Sparrow, Malcolm Doney, Petra Feriancová and Amanda Kyritsopoulou all draw inspiration from daily life. I end with two exhibitions on themes of diversity and inclusion.

The centenary of Souza’s birth provided many opportunities through exhibitions in India, the UK and the US to see his work and reassess his achievements and legacy. The most recent exhibition took place at Snape Maltings using works from the Britten-Pears Art Collection. Souza was not only a prolific painter but also a writer, poet and even philosopher. His legacy is only just coming to light, and there is much more still to research.

‘Darkness’ at The Red House in Aldeburgh provides a current opportunity to see work by Souza as part of an exhibition of monochromatic works by artists such as David Hockney, Josef Scharl, Sidney Nolan, and Christian Rohlfs, all of which were collected by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears. The exhibition offers a rare opportunity to experience a selection of striking monochromatic works from the Britten-Pears Art Collection. These are powerful works usually kept behind closed doors.

Francis Newton Souza, Grosvenor Gallery, Snape Maltings, Suffolk

Born in Goa, India, to devout Christian parents, Souza began his art education within the strictures of British colonial art school teaching in Bombay. Pushing against these boundaries, he started to take inspiration from modernist practices from Europe. He began to achieve some acclaim in India, but, hoping to gain greater recognition, he moved to London in 1949. After some initial hardship, a prolific period followed, and he had a number of solo shows. Souza became disappointed by what he felt was a general apathy towards contemporary art and culture in the UK, and in 1967, he moved to New York, where he spent the rest of his life.

He said that: ‘Renaissance painters painted men and women making them look like angels. I paint for angels, to show them what men and women really look like’ (quoted in 1960 by Edwin Mullins). George Melly has described well in ‘Religion and Erotica’ the savage cross-hatching and cubist fragmentation of forms, which means ‘that there is no overt sentimentality in the artist’s religious iconography’. Indeed, Melly suggests, ‘he expresses no obvious belief in redemption, only in suffering’ as he ‘seems to attack his evocations of the sacred with angry cross-hatching to the point of near obliteration.’

Melly writes: ‘Every artist to be reckoned with tends to invent their own trademarks. In Souza’s case, the religious work, especially the very small forehead … a portrait of Christ, his neck and torso pierced by two symbolic arrows, leaving hardly any room to jam on the crown of thorns. The eyes, too, are unnaturally high in the head, and in this case, as in many others, blacked out. In this drawing, for example, Jesus weeps rods rather than tears, framed by … fish skeletons … This comparatively common device is used not only to represent tears, but beards and hair are quite often treated in this way. The arrows also appear elsewhere, surely a symbol of suffering, borrowed from that pincushion, St Sebastian.’

In this, Souza was influenced firstly by the Roman Catholicism of his youth. He wrote of seeing ‘the enormous crucifix with the impaled image of a Man supposed to be the son of God, scourged and dripping, with matted hair tangled in plaited thorns.’ Secondly, he was influenced by the modernist movement and the work of Picasso in particular. Roger Wollen, in writing of ‘The Crucifixion’ from 1962, now in the Methodist Church Collection of Modern Art, describes this work as ‘overtly expressionist in style and the figure on Jesus’ left … is conveyed in a cubist style, with four superimposed eyes, two looking at Jesus and two looking out of the painting at the viewer.’ The result, in the words of Nevile Wallis, are great crucifixions; ‘barbaric in colour’ with ‘scrawny jagged forms, and thorny shapes’ burning in their ‘terrible conviction’.

As Edwin Mullins writes in ‘F. N. Souza’: ‘Souza’s treatment of the figurative image is richly varied. Besides the violence, the eroticism and the satire, there is a religious quality about his work which is medieval in its simplicity and in its unsophisticated sense of wonder. Some of the most moving of Souza’s paintings are those which convey a spirit of awe in the presence of divine power … in his religious work, there is a quality of fearfulness and terrible grandeur which even Rouault and Graham Sutherland have not equalled in this century.’

Twenty years ago, Roger Wagner and a group of fellow artists – The Metaphysical Painters – set out on the first of a series of annual pilgrimages to places associated with poets, painters and writers who transfigured the landscapes in which they lived. The poems and paintings inspired by these journeys gave rise to a book, ‘The Farther Away’, which weaves the poems together in a narrative that begins in a Japanese bamboo forest and ends on a pilgrimage through Wales to Ynys Enlli, ‘the island of twenty thousand saints’. The book weaves together poetry, prose, and paintings that describe these journeys and respond to artists like Samuel Palmer, George Herbert, Thomas Traherne, and William Blake. ‘Roger Wagner: The Farther Away’ at MOCA Machynlleth tells the story of those pilgrimages in the images produced by the group, which, in addition to Wagner, includes Mark Cazalet, Thomas Denny, Richard Kenton Webb, and Nicholas Mynheer.

On the first day of Spring 2022, Sophie Hacker started a one-year Art Residency at Gilbert White’s House & Gardens. Her Gilbert White & The Book of Nature exhibition there in July and August 2025 showcases some of the installations, sculpting, painting and experimental work made during the residency and as a direct result of the research and development undertaken for that year.

Hacker specialises in Church Art. She is an advisor for Art+Christianity, the UK’s leading organisation in the field of visual art and religion, and a Visiting Scholar at Sarum College. Since 2006, she has been involved in both the display, production and curation of artworks for Winchester Cathedral. She is also an Artist Liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Glaziers and Painters of Glass, and a member of the British Society of Master Glass Painters. Recent commissions include stained glass windows, chapel crosses, vestments, altar frontals, and ecclesiastical silver, as well as a range of private commissions in sculpture and glass.

In February 2024, she installed a permanent commission for St Marylebone Parish Church, London. That project was featured on a recent episode of BBC1’s Songs of Praise, celebrating the 200th birthday of the National Gallery. Current projects include designing a reliquary for the bones of a seventh-century royal saint in Kent, a bronze owl for a private client in Cambridge, and a large Orrery for a private estate in central France.

The Society of Catholic Artists (SCA) is exhibiting at 54 The Gallery in August. The SCA was founded in 1929 as part of the centenary celebrations for Catholic emancipation in Britain and was originally known as the Guild of Catholic Artists and Craftsmen. It aimed to foster a community of Catholic artists and craftspeople, promoting both their artistic endeavours and their shared faith. Glyn Philpot served as its first President, and notable artists such as Frank Brangwyn, Graham Sutherland, and Arthur Pollen were among its early members.

Membership is open not only to practising Catholic artists but also to all Catholics interested in the visual arts and to those who support the aims of the society. Their membership includes painters, stone, wood and metal sculptors, architects, stained glass artists, potters and iconographers. They have always aimed to raise the standard of religious art and encourage Christian fellowship among artists, while also being available to advise prospective patrons and recommend suitable artists for commissions. Members have been responsible for major artistic work for cathedrals and churches throughout Britain. A varied programme of meetings and outings is arranged each year, together with exhibitions and workshops.

The Methodist Modern Art Collection is coming to Bradford this autumn. ‘Everything is Connected’ will be displayed across five venues in Bradford city centre, Ben Rhydding, Thornton and Apperley Bridge. A total of 23 original works from the Collection will be exhibited, including stained-glass work ‘Preaching’ by George Walsh and abstract oil painting ‘Love Triumphant’ by John Reilly, both new acquisitions to the Collection, on display for the very first time. Respective themes at the venues include “peril”, in relation to faith, the environment, climate change and the impact of conflict around the world; women artists from the Collection; and what hope means to a school community with an international student population.

Verity Smith, Faith and Arts Development Lead, and manager of the project explains: ‘MMAC Bradford 2025 is enabling opportunities for a variety of creative activity, and we are thrilled to be able to collaborate with an Artist in Residence and a Creative Writer in Residence.’ The exhibition hopes to connect visitors with the artworks in innovative ways through the telling of new stories, exploring hidden and overlooked histories, considering contemporary global concerns, women’s history, and uncovering diverse and marginalised heritage. Creative responses to the Collection through workshops and events will enable and support reflection on the themes across diverse communities.

The Methodist Modern Art Collection is one of the Church’s greatest treasures. It is an outstanding collection of 20th- and 21st-century religious art, founded in 1962 by Dr John Morel Gibbs during the post-war revival in British religious painting. Since then, it has grown to comprise more than 60 paintings, prints, drawings and sculptures, including examples of British 20th-century paintings by Graham Sutherland, Elisabeth Frink, Patrick Heron and Maggi Hambling, as well as examples by South Asian artists F N Souza and Jyoti Sahi. The Collection has enhanced worship, opened faith conversations, amazed visitors, and inspired different art forms, including poetry and dance.

“We are delighted to be exhibiting works across Bradford as part of the City of Culture programming for Bradford 2025. It is hugely rewarding to see communities already responding to the Collection and how differently our works speak to individuals. It is also exciting for us to see our first Artist and Writer in Residence programmes take shape. A varied programme of events is being planned during the exhibition, and we look forward to the opening celebrations in early September,” said Professor Ann Sumner, Chair Methodist Art Collection Management Committee.

The five main venues are: Ben Rhydding Methodist Church – Peril in relation to the environment, climate change and the impact of conflict around the world; Bradford Cathedral – South Asian arts and heritage; South Square Centre, Thornton – Women artists and the legacy of the Brontes; St James Church, Thornton – Women in the Bible; and Woodhouse Grove School Chapel – Hope and what that means to the school community on an international level.

Installation view of Worship Paintings: Tanya Ling, The Mayor Gallery

Worship Paintings is a solo exhibition of new works by Tanya Ling, comprising a series of large-scale, single-colour Line Paintings – rendered for the first time in oil on linen. These paintings are not images of worship, but the result of it. Committed to a single colour per canvas, each work is constructed through a choreography of continuous line, drawn slowly and with resolve. What unfolds is not a pictorial event, but a durational act, making the paintings devotional in the truest sense: not symbolic, but lived.

Andrew Renton has described Ling’s work as a form of “faith in motion,” noting her capacity to conjure endless variations of what appears, at first, to be the same painting. That paradox – of the infinite within constraint – is central to Worship Paintings. The line doesn’t change, yet it is never the same. The act becomes a kind of channelling, more spoken than composed.

The aesthetic lineage that runs through these works recalls the urgency of Cy Twombly, the restraint of Brice Marden, the momentum of Joan Mitchell, and the chromatic release of Helen Frankenthaler – artists for whom abstraction was a form of attention as much as expression. There is no attempt here to resolve painting, or to explain it. Worship Paintings understands painting not as an object of veneration, but as an act of worship – a channelling of something beyond the self, offered through repetition and restraint. As Renton notes, Ling’s practice evokes the infinite: a seemingly inexhaustible capacity to generate variation within strict formal limits. Each painting arrives like a spoken prayer – not composed, but received. A gesture toward eternity, enacted one line at a time again, again and again.

Where the River Burns, a site-specific solo exhibition by French artist Juliette Minchin, marking her first presentation in Istanbul. Curated by Anlam de Coster, the exhibition unfolds across the 16th-century Zeyrek Çinili Hamam’s recently unearthed Byzantine cistern and cold rooms.

De Coster invited Minchin to develop a site-specific project in dialogue with the hammam’s layered material history, architectural memory, and enduring rituals. Her intervention, grounded in the alchemical transformation of materials such as wax, tin, and paper, explores themes of purification, divination, and care.

Where the River Burns weaves together ritual, architecture, and the transformation of materials through heat. Minchin’s installations exist between the sacred and the domestic, the monumental and the intimate. Whether in wax, tin, or paper, she captures ephemeral traces of desire, gestures of care, and acts of devotion—transforming the hammam into a space where material becomes metaphor, and the river of ritual begins to burn.

During her time in Istanbul, the artist was also inspired by the city’s devotional vernacular, as well as its gestures of offering and wish-making. One new work is made from half-burnt candles collected from local churches. Once lit in hope, these remnants are transformed into a sculptural vessel for collective longing, memory, and spiritual residue.

The exhibition follows a sequence inspired by the ritual structure of a traditional hammam visit. Upon entering the subterranean cistern, Minchin’s signature wax drapery installations create a symbolic threshold. Process-based works continue through the cistern’s passageways, including new pieces from her Hydromancies series—delicate drawings on translucent paper created through the interplay of water, pigment, and fire. These works resemble celestial maps and palmistry, echoing both scientific and mystical traditions tied to hammam culture and Barbarossa, the original patron of Zeyrek Çinili Hamam.

Minchin also draws from the ancient practice of molybdomancy (divination using molten metal) with a new series of tin installations created in Istanbul. In the cistern’s otherworldly setting, tin flows and solidifies into lace-like, reflective forms, evoking rivers, relics, and the reading of omens in molten matter. Other tin works directly respond to the restoration of the hammam, referencing historical objects uncovered during archaeological excavations.

Canada Choate writes that although ‘Marian Spore Bush painted the flowers, animals, prophets, and architectures on view in Life Afterlife, Works c. 1919–1945 [at Karma in New York], she insisted that she was but the conduit for spirits telepathically controlling her hand from another realm. In communion with, as she recounted, “the souls of those who have lived here on earth from far-distant times down to the present moment,” Spore Bush worked automatically around the same time that the European Surrealists were popularising automatic drawing and the New Mexican Transcendental Painting Group was representing spiritual concerns through abstraction. However, she did so without any knowledge of the then-current avant-garde movements. Life Afterlife is the first exhibition of her work in nearly eighty years.’

Bob Nickas writes that: ‘… born 1878 in Bay City, Michigan, where Marian Spore Bush would go on to a successful dentistry practice of nearly twenty years; the death of her mother in 1919, and her use of the Ouija board as a means to remain in contact with her, investigations which led to Spore Bush herself being contacted by entities, the spirits of dead artists she said, compelling her to paint, even as she had no previous interest nor training in art; her move to New York in 1920, where she set up a studio and began to show her art, attracting attention for its otherworldly origins even as she didn’t consider herself to be a medium (she would be championed by the illusionist and escape artist Harry Houdini, well known for exposing frauds among so-called spiritualists, but who considered her connection to the supernatural genuine); her philanthropic work in the late-1920s, helping to feed and clothe the needy in a time of economic desperation; her marriage to Irving T. Bush, a wealthy businessman, in 1930; and the major shift in her art to a darker vision in the early 1930s, and an unequivocal position taken against global conflict. She would live to see the war’s end, passing six months later, 24 February, 1946.’

Nickas notes that: ‘These multiple engagements and identities over the span of sixty-seven years … evidence lives plural, a life following many intersecting and diverging lines, in itself a concise visualisation of the auditory and imagistic guides she would follow in creating her art.’ He explains that ‘The reappearance of her work in this moment, as of many others in recent years, is a reminder that art history is a matter of detective work’ and asks ‘What is this artist’s place in it’ and ‘How do we locate her in relation to other artists in this period, few of whom were aware of one another in their time?’ He notes five artists in particular: ‘Looming above what is now an alternate view of art’s path—pathways, more accurately—across the twentieth century, is the Swedish mystic Hilma af Klint (1862–1944). She precedes Spore Bush (b. 1878), the German-American transcendentalist Agnes Pelton (b. 1881); the Swiss artist and healer Emma Kunz (b. 1892); Paulina Peavy (b. 1901), who was guided across five decades by an entity encountered during a séance in 1932; and Gertrude Abercrombie (b. 1909), known for her mysterious, dreamlike paintings.’

Sean Scully: The Albee Barn, Montauk is a survey of the artist’s work ranging from 1981 to 2024, exploring his Long Island connection and how a single month spent in Montauk in the summer of 1982 with a fellowship at The Edward F. Albee Foundation became a pivotal place and moment in the artist’s career.

The Edward F. Albee Foundation has maintained the William Flanagan Memorial Creative Persons Center (better known as ‘The Barn’) in Montauk, on Long Island in New York, for almost 60 years, which exists to serve writers and visual artists from all walks of life by providing time and space in which to work without disturbance. Located approximately two miles from the centre of Montauk and the Atlantic Ocean, ‘The Barn’ rests in a secluded knoll which offers privacy and a peaceful atmosphere.

It was in 1981 that Scully broke the hold of Minimalism with his manifesto painting ‘Backs and Fronts’. There was a return of colour and space. Brushstrokes were now visible, broken free of the constriction of taped lines. However, it was the following summer, in 1982, spent in Montauk, that provided the artist’s first intimate encounter with nature; an experience that, for Scully—brought up in highly urban environments—was decisive. A month of painting in the Albee ‘Barn’ gave Scully the freedom to produce small multi-panel works on found scraps of wood as a direct response to the movement of light and the environment around him, an approach that has been a touchstone in Scully’s work ever since.

This exhibition recalls that transformative moment by bringing together 15 of the original 1982 Montauk paintings for the first time since their time in the Barn, in the same geographic region near the site where they were inspired and produced 43 years ago. The exhibition includes over 70 works in total, chosen in collaboration with the artist to highlight the works’ contextual site, landscape and light. Further rooms are filled with important paintings such as ‘Backs and Fronts’, ‘Heart of Darkness’, the ‘Wall of Light’ series last seen in New York at the Metropolitan Museum in 2006, the ‘Landline’ series last exhibited at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in 2018, and the Wadsworth Atheneum in 2019, to the more recent ‘Wall Landlines’, and the first ‘Tower’ painting, a new series of monumental assemblage paintings started in 2024 and exhibited here for the first time.

The interaction between the natural and the artificial is a focus for David Stone’s ‘Near the Edge’ exhibition at Chappel Galleries. He writes: ‘Our view of landscape is generally that of a vista, an open view spread before us. If worked upon by human labour, such a view could be seen as a historical record involving generations of people working on the face of the earth. However, I wanted to look beyond that to the unnoticed areas that might have involved involuntary human intervention. Blue plastic had a particular draw because blue on the ground inverts the natural order of things, and it is surprisingly easy to find. But that led to the concept of the aerial view, not looking across but down. Some of the vertical views shown here are from an altitude of one metre, but others are from much higher up. Roads, trees and hedges seen from hundreds of metres high echo the shapes that can be found in ground-level bushes. And at this level it all joins up, natural patterns being repeated endlessly.’

Lucy Sparrow, Fish and Chips 2025, Bourdon Street Chippy, Lyndsey Ingram

After eight months of designing, cutting out, sewing, stuffing, and painting, Lucy Sparrow’s Bourdon Street Chippy is open in London’s Mayfair at the Lyndsey Ingram Gallery, transforming a classic British fish and chip shop into a fully immersive, felt-filled installation. Sparrow is known for transforming everyday spaces into soft, immersive installations that blur the line between art, humour, culture, and nostalgia.

Here, she has recreated every detail of the beloved takeaway – from battered cod and chunky chips to curry sauce, pickled eggs, and fizzy drinks – all entirely handmade from felt. With her signature charm and attention to detail, Sparrow has turned a familiar high street staple into a tactile celebration of food, memory, and British culture.

Visitors are invited to order their usual Friday night supper, take in the sights of the portrait wall, and pose in front of the wall of sauce for a photo, blurring the boundaries between art installation and nostalgic experience. Every element of the show is hand-sewn, right down to the cutlery and paper cones.

Malcolm Doney’s work is similarly inspired by the mundane and everyday. He says, ‘I’ve always loved everyday things: a mug of tea and a bacon sarnie; a soft jumper that’s fraying at the sleeves; walking the dog down a familiar path. Domestic, functional things, like kitchen implements or garden sheds – especially when their edges have been eroded by use or age – have a kind of vernacular beauty. I look for and discover what the metaphysical poet George Herbert called “Heaven in ordinary”.’

His works are a pared-down vision of ‘folk’ or ‘naïve’ art, and the liberties it takes with perspective, proportion and colour. He likes to explore the abstract qualities in simple, familiar objects in the spirit of artists like Pierre Bonnard and William Scott. It is important for him that his practice is earthed, grounded, and that any spiritual qualities that may emerge (in his work) are essentially a by-product, not an intention.

Neighbourly Pursuits & Curious Works from Angel Lane, Blythburgh, at the Courtyard Gallery in Aldeburgh sees him joined by his neighbour, Jeff Fisher, who hails from Melbourne, Australia, where he studied fine art. The bulk of Fisher’s work has been artwork for book covers, as well as working in design and exhibiting regularly in London and Paris.

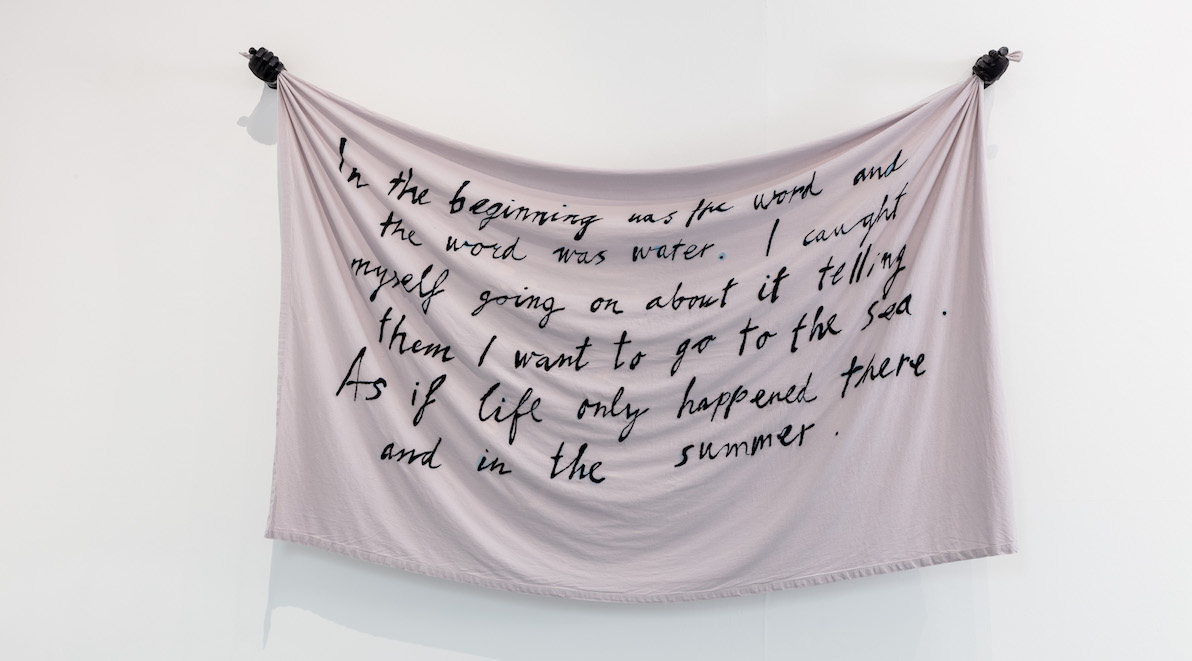

A further exhibition from artists inspired by the intimate rituals of daily life can be found at Elizabeth Xi Bauer’s Deptford space, where they are presenting ‘The Fabric of Life’, a duo exhibition by Petra Feriancová and Amanda Kyritsopoulou. The exhibition brings these two artists into creative dialogue following their first encounter in the gallery’s Summer Show.

Drawing on their archives and symbolic frameworks, both artists explore how meaning emerges through repetition and disruption, attending to the often-unseen systems that shape experience. Their works address the personal and psychological alongside political and mythological themes, merging the private with the utilitarian. Everyday items—such as cutlery, shells, stains, and clothing—are reimagined as carriers of significance, transformed from the residue of lived encounters.

Feriancová presents a constellation of new and recontextualised works—suspended fabrics, objects, and photographic series—tracing intersections between motherhood, the quotidian, and political memory. Modest gestures and domestic rituals form her visual lexicon: in one series of postcards, hands are shown in various positions, moving from the banal to the magical. She describes her photographs as “small epiphanies,” pairing image and language as parallel systems, each with its own rhythm and opacity.

Feriancová’s practice centres on subtle acts of transformation. Found materials are juxtaposed with household items: dried swordfish echo the form of knives; watermelons mirror stones; chopping boards slice through language.

Kyritsopoulou’s work examines repetition, routine, and emotional drift through sculptural photographs and staged object arrangements. Drawing on the aesthetic languages of consumer culture, sport, media, and design, she creates constellations of objects that speak to the entanglements of contemporary life. Her Perspex-mounted shirt series pairs high-resolution scans of crumpled garments with the garments themselves, forming a choreography of torsos across the wall. Humorous yet incisive, works such as ‘Too close to the ironing board’ address absence, labour, and blurred identity.

She also presents a text-based work — I’ve been good, I’ve been good but not as good as I could have been… — printed on receipt-like paper emerging from a tissue box, its message almost hidden in plain sight. She says: ‘I’m interested in distorting reality ever so slightly, as a way of testing perception and opening multiple modes of response and connection to the world. It’s about confronting the personal through the completely insignificant or overlooked and exploring its potential to resonate.’

Tache is a new contemporary art gallery in London’s Fitzrovia dedicated to nurturing, supporting and showcasing emerging artists, and dismantling the barriers that many artists face in their early-career development. Lauren Fulcher, Project and Gallery Manager at Tache, explains: ‘At Tache, we are dedicated to championing bold and diverse contemporary voices and empowering emerging artists by providing a platform for their first solo shows, in the heart of London. We’re thrilled to present the work of Betty Ogun, an artist whose practice embodies the very spirit of experimentation and cultural inquiry that drives our mission.’

‘LOVE/FIGHT’ is the debut solo exhibition of new and recent works by Ogun, a London-based multidisciplinary artist. The exhibition features large-scale paintings, photography, textiles, sculpture and video, exploring Black womanhood through the intersecting perspectives of militant femininity, new wave feminisms, and feminine resilience, portraying scenes that reflect both strength and struggle. Ogun’s ‘Fight’ series is a bold collection of paintings that meditate on survival, endurance and self-expression through conflict. ‘Thinking’ and ‘Mother and Baby Unit’ are celebrations of motherhood, which are symbolic of the experience as life-changing and uniquely difficult.

Ogun comments: ‘This solo exhibition stands as a manifesto of everything my work embodies — resilience, emotional expression, and a life lived expeditiously. Through this show, I aim to illuminate often-overlooked narratives and invite reflection on how documenting adversity and conflict through art can serve as a powerful tool for empowerment, healing and community building.”

Finally, ‘Touch: Beyond Vision’ is more than an exhibition — it’s a movement toward inclusive creativity. By reimagining iconic artworks and treasured photographs as tactile experiences, the exhibition opens the world of visual culture to those who navigate life through senses beyond sight.

At the exhibition, visitors can explore more than 20 tactile artworks created using Carveco’s relief technology. The Collection includes pieces that represent well-known musicians, landmarks, historical figures, artworks, and icons. There is also a mural wall that displays personal photographs contributed by members of the blind community, made touchable through 3D printing.

Each artwork includes audio descriptions, braille labels, and clearly designed touchpoints to support independent exploration. Staff members will be available to explain how to interact with the exhibits and assist as needed.

This exhibition is designed for visitors who are blind or visually impaired, as well as those interested in accessible design and inclusive experiences. It’s open to families, educators, artists, and the general public.

‘Darkness’, 3 April – 2 November 2025, The Red House, Aldeburgh – Visit Here

F.N. Souza – Visit Here

‘Roger Wagner: The Farther Away’, 14 June — 30 August 2025, MOMA Machynlleth – Visit Here

‘Gilbert White & The Book of Nature’, 8 July to 17 August 2025, Gilbert White’s House – Visit Here

Society of Catholic Artists, 19 August – 30 August, 54 The Gallery – Visit Here

‘Everything is Connected’, From 1st week of September – 12th October 2025, Venues: Ben Rhydding Methodist Church; Bradford Cathedral; South Square Centre, Thornton; St James Church, Thornton; and Woodhouse Grove School Chapel – Visit Here

‘Worship Paintings: Tanya Ling’, 31 July – 6 September 2025, The Mayor Gallery – Visit Here

‘Juliette Minchin: Where the River Burns’, 19 September 2025 – 18 January 2026, Zeyrek Çinili Hamam, Istanbul – Visit Here

‘Marian Spore Bush: Life Afterlife, Works c. 1919–1945’, 9 July – 6 September 2025, Karma, New York – Visit Here

‘Sean Scully: The Albee Barn, Montauk’, 11 May – 21 September 2025, Parrish Art Museum – Visit Here

‘David Stone: Near the Edge’, 30 August – 28 September 2025, Chappel Galleries – Visit Here

‘The Bourdon Street Chippy’, 1 August – 14 September 2025, Lyndsey Ingram Gallery, London – Visit Here

‘Neighbourly Pursuits & Curious Works from Angel Lane, Blythburgh’, 4 September – 9 September 2025, Courtyard Gallery, Aldeburgh – Visit Here

‘Petra Feriancová and Amanda Kyritsopoulou: The Fabric of Life’, 12 September – 25 October 2025, Elizabeth Xi Bauer, Deptford – Visit Here

‘LOVE/FIGHT’, 18 September – 23 October 2025, Tache – Visit Here

‘Touch: Beyond Vision. Art you can feel. Stories you can touch.’, 15 September 2025, OXO2, London OXO Tower – Visit Here

Lead image:

Petra Feriancová, In the beginning was the word and the word was water. I caught myself going on about it telling them I want to go to the sea. As if life only happened there and in the summer, 2017/2025. Embroidery on cloth, wooden hands, black gloves, 145 x 208 x 25 cm. Photograph: Richard Ivey. Courtesy of the Artist and Elizabeth Xi Bauer, London.