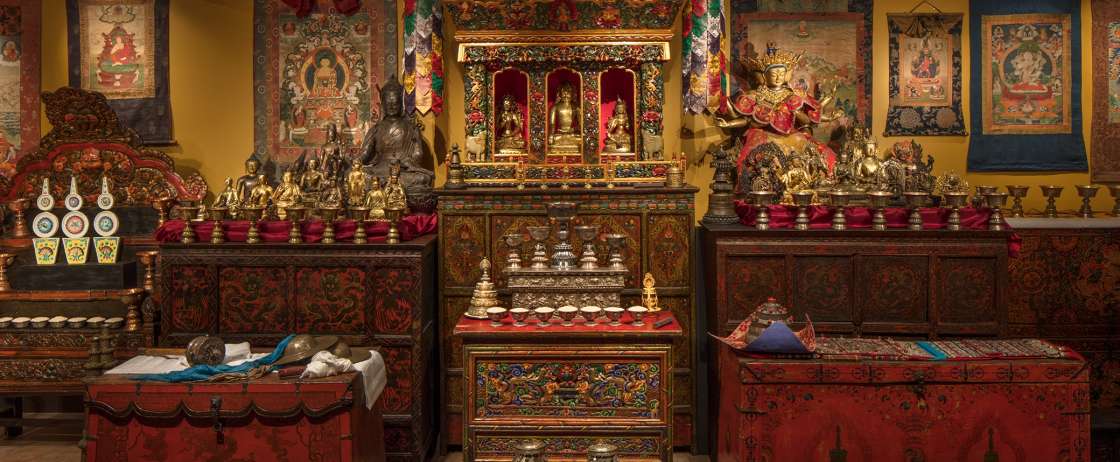

The Rubin Museum is an oasis of calm and beauty. A much respected and cherished environment for its clean, modern architectural symmetry, presenting the most excellent of historic and contemporary eastern cultural works in its cylindrical vessel of artistic and spiritual ideals. Walking up the spiral steel staircase leads to an enlightened graduation of the mystical world of ceremony; as every floors flavor breathes symbolic expression with eastern religious iconography and religious practices realized through the creative imagination.

With their recent show The Force of Stillness, curated by Amber Bemak, an investigation into the influence of Buddhism on art, the physical flow of the body wedded to the quieting of the mind, was ever present and enhanced by an array of five performers dressed in pure fresh white. We journeymen and women were guided by Harry Einhorn with Samadhi Arts to put on our headphones and follow him through the exhibits, while beautiful goddess dancers improvised on the enchanting spirit of each display. Music and sound from distant lands drew us into the well of knowledge and calm which Buddhism embodies. It was the perfect fusion of all the elements — heart, mind, and body. Bernak explains how the vision for this show was awakened in her mind.

I have been wanting to do this for about five years. I actually had the idea for the festival while I was in a meditation retreat at Nagi Gompa in Nepal. Many of the artists in the show were the ones I scribbled initially down in the middle of my meditation session when the idea came five years ago. In terms of having it at the Rubin, my own film work has been shown there many times and I am familiar with the museum in that way. I somehow thought that it would be perfect there, even though the Rubin mostly shows more traditional Himalayan and Buddhist art. In the spirit of my idea- which is to diversify the representation of Buddhism in contemporary art.

How and why did you decide on all the elements of the program?

Mainly I wanted works that do not fit into the contemporary stereotype of Buddhist art. Tibetan Buddhism involves all of the emotions- negative and positive- and their purified aspects. For example, the emotion of anger purified is mirror-like wisdom or desire purified is discriminating wisdom. In most artistic depictions of Buddhism made in the United States (except for thankas of wrathful deities/dakinis which are usually not contextualized properly) I generally see the calm, sweet, and quiet aspect of Buddhism portrayed. I think this feeds into US culture’s very orientalist and sort of antiquated appropriation of Buddhism, and is additionally an aggressive way of viewing a religion. The aggressiveness comes from not having a more holistic view of Buddhism by removing it from it’s historical and cultural context to adapt completely to another fantasy altogether. I know historically as Buddhism has moved around the world it’s done that, but as I’m here on the planet for this moment when it’s moving into the US, Latin America, and Europe- I am critical of the way it’s doing that. The work I showed is dynamic. It is filled with energy. Some of it is angry, some of it is sexy, some of it is disturbing, some of it is poetic, and most of it is not gentle and sweet. I wanted a full display.

Bemak and her colleagues perfectly matched up film, movement, and performance, diving into the meditative process. With an innovative stroke of virtuosity, Zach Layton, one of New York’s inspired dexterous musicians, created an experimental experience emanating sound from his mind in a state of stillness.

Layton explains: I use an EEG which reads brainwave signal and then translates this signal into sound using original software developed in Max/MSP on the laptop. I’m interested in the rhythmic activity produced by the human autonomic nervous system. The firing of neurons in synchrony and how this ultimately emerges into the rhythm of consciousness.

It was this interest in neurofeedback technology (and the music of John Cage) that actually led me to meditation and, eventually, Buddhism. About 10 years ago I began to experiment with eeg technology and performed with this system during one of the Issue Project Room floating points festival, spatializing the signal throughout Stephan Moore’s 18 channel speaker system.

Around this time, I was introduced to the teachings of Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche by my friend Jeff Sable (who had studied with him in Nepal). Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche is one of the foremost practitioners of Dzogchen, This practice was a revelation for me and has been a part of my life ever since. I attended a number of retreats with CNR and met Amber at the first one of these. She had been working for him at the time in Nepal.

The festival presented experimental films and performances that facilitate and transmit a complex range of meditative experiences while addressing topics such as visual colonization, queer performativity, alternate experiences of temporality, and experiments with meditative gestures in public.

I asked Amber Bemak about all these different features and what they meant.

In terms of visual colonization, I was referring primarily to Trinh T. Minh-ha’s work. I believe that she is one of the great contemporary artists dealing with this topic in brilliant ways. Because United States-based artistic representation of Buddhism (and many other things!) is so related to an aggressive, colonizing set of visuals manifested through a consistent re-creation of a romantic Shangri-la without any attention to nuance, history, or cultural context, I wanted to feature an artist who is working with this. Trinh T. Minh-ha’s work is Tantric in the way that it utilizes and references poetry, anthropology, ethnography, and experimental film to dismantle and investigate the true nature of the structure of these things.

As an artist who is deeply invested in queer representation, I was interested in programming work which deals with gender performativity. Many of the works in the festival- from Mazen Khaled’s Hypnopompic to Narco by Nadia Granados offer variations on that. This notion of a performance of gender is directly linked to Buddhist philosophical frameworks about the lack of a solid self. Both theories posit that the self is performed and that this performance is not static, but instead changes constantly.

Going back to Trinh T. Minh-ha as a reference for alternate experiences of temporality, she has written widely on movement and stillness, and how these things exist inside of each other. She frames time as non-linear, and cinematic time as even less so. Buddhist meditative experience is time disrupted, re-imagined, and revitalized, as in this state, temporal references are removed, and the very texture of time expands into a plurality of possibilities. The Past, present, and future are neither present nor absent. Positioning Buddhist meditative experience and experimental film as two modes of cultural practice generating radical non-linear temporality, the work was shown in Force of Stillness addresses and facilitates an experience of nonlinear time, allowing the audience to participate in shifts of perception which challenge socially conditioned temporal notions.

Babeth VanLoo’s performance during Force of Stillness consisted of three 24-minute experiments with meditation in public space. In her first performance, she stands alone, in her words “clearing the space.” The second involved her inviting people to come and sit with her and hold her hands. The third was what she called a “compassion tree,” where she invited people to hang on a constructed tree their ideas about compassion, and also tell her about their first experiences with compassion.

Compassion, wisdom, and quiet minds are exactly what we all need right now

Words Isa Freeling © artlyst 2016 Photo: Courtesy The Rubin Museum New York

Force of Stillness @ The Rubin Museum New York